IRS Ruling May Force Business Out of Athletics : Sponsors: A decision to make nonprofits pay taxes on corporate contributions could affect events all the way to the Olympics.

- Share via

If the action starts to drag during one of the 17 college football bowl games to be televised between Christmas and New Year’s Day, you might amuse yourself by counting the corporate logos that flash on the screen.

That, in a sense, is what the Internal Revenue Service is doing.

Under pressure to boost tax receipts, the IRS has targeted the hundreds of millions of dollars that corporations pay to sponsor athletic events.

In a recent opinion affecting two bowl games, the IRS ruled that such funds amount to advertising fees, not charitable contributions, so the nonprofit organizations putting on the games must pay taxes on them at the full corporate rate of 34%.

And if the Cotton Bowl and the John Hancock Bowl weren’t sacred enough, partisans say the ruling threatens everything from Olympic sports to major charities to public television’s “Masterpiece Theater.”

More than 100 senators and congressmen have signed legislation that would reverse the ruling.

As a lawyer involved in the fray observed: “There aren’t many people in Congress who don’t have an alma mater, and there aren’t many who don’t like the Olympics.”

It wasn’t long ago that television rights fees made up the lion’s share of revenues for the bowl games. Since they were footing the bill, the networks wouldn’t even allow corporate advertising in the stadiums within camera range.

But in recent years, the TV spigot has tightened, forcing organizers to lean more heavily on corporate sponsorship. Twelve of the 18 major bowl games now have “title” sponsors. Besides the John Hancock Bowl in El Paso and the Mobil Cotton Bowl in Dallas, they include the Federal Express Orange Bowl in Miami, the USF&G; Sugar Bowl in New Orleans, the Mazda Gator Bowl in Jacksonville and the Poulan/Weed Eater Independence Bowl in Shreveport, La.

Corporate sponsorship has become the dominant funding source--sometimes the sole reason for existence--for other events, as well. Fortune 500 logos abound on golfing’s PGA Tour, for example, where many tournaments are run by nonprofit groups and $20 million was raised for charity in 1990.

“I think every nonprofit event organizer is worried that they might be next,” said Jim Roberts, editorial director of Special Events report. The Chicago-based trade publication estimates that $1.1 billion in sponsorship money is generated annually for sporting events, cultural festivals, art exhibitions and the like.

In the John Hancock and Cotton Bowl case, which surfaced publicly just before Thanksgiving, the IRS advised its field office in Dallas that it should treat the sponsorship payments--about $1.5 million from Mobil and $1 million from John Hancock--as fully taxable “unrelated business income.”

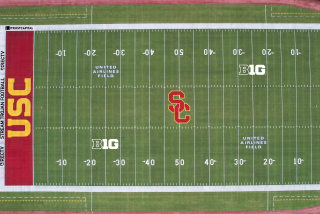

The IRS reasoned that taking money in exchange for placing sponsors’ corporate logos on the 50-yard line and on players’ uniforms and so forth constitutes an advertising business that is unrelated to the educational purpose for which the nonprofit organizations had been established.

On the other hand, the IRS considers TV rights payments to be licensing fees, in accord with the organizations’ purpose and thus non-taxable. It’s thorny terrain, legally.

“How this is unrelated is beyond me, when without the sponsorship money there’d be no game,” said Jack Mahoney, sports marketing consultant at John Hancock in Boston. “The function of a bowl is to put on the bowl.”

Organizers contend that crediting sponsors is the only practical way to recognize their contributions, little different from naming a chemistry lab after the alumnus who endowed it.

The bowl game ruling did not represent a new line of thinking by the IRS, however. Last year, the agency demanded more than $1 million in back taxes from Ohio State University based mainly on income from scoreboard advertising at Ohio Stadium.

And the national governing bodies for amateur gymnastics, soccer, volleyball and water skiing have either already received or are anticipating similar IRS rulings.

“What the IRS is doing I believe is unconscionable,” said Janet Achterman, controller at Ohio State, which is appealing its case.

Achterman argued that if the IRS really wants to treat universities as businesses, fine--let them tax the schools’ profits, if any, after expenses, rather than just focusing on high-profile athletic revenue. “They are cherry-picking only those areas that have any money connected with them,” she said.

The bowl organizers and sports federations plan to fight the rulings administratively and in court if necessary.

Meanwhile, event organizers facing a 34% cut in sponsorship revenue have two options, said John Hewett, controller of the U.S. Gymnastics Federation in Indianapolis: “Either they’ll cut back or they’ll ask (sponsors) for more. Asking for more is probably not that viable in today’s market.”

No kidding.

“If the Cotton Bowl came back to us and said, ‘Well, we need more money,’ there wouldn’t be any,” Mobil spokesman Peter A. Spina said.

An event as popular as the Cotton Bowl could survive, but what if sponsorship funds for the Public Broadcasting System series “Masterpiece Theater” and “Mystery!” suddenly became taxable because of the familiar credit line, “brought to you by a grant from Mobil Corporation”? Since Mobil carries the whole budget, Spina said, any cuts mean fewer shows.

He finds it ironic that the IRS’ aggressiveness comes at a time when government is urging the private sector to make up for reductions in public support for schools, museums and other such institutions.

“So what they’re saying now is, we’re not only not going to help, we’re also going to take 34%,” Spina said. “Could this change corporate America’s attitude toward giving, if they knew 34% was going to the IRS? I really think it could.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.