NFL PLAYOFFS : Potatoes to Gravy : Rypien and Kramer Weren’t Big-Name Quarterbacks, but They Have Reached NFC’s Big Game

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Play it again. Just the mood music, please. For here is a strange tale of two surging quarterbacks:

--Just a year ago, one of them was unemployed. He knew where his next meal was coming from, possibly, but not his next job.

--The other, a veteran NFL starter, also seemed to be a failure. As inconsistent as ever in his fifth pro season, he ended it by throwing three interceptions in an erratic postseason start last January, taking his team out of the playoffs.

Two troubled quarterbacks--and where are they now?

Well, this week, as it happens, they are both in the nation’s capital.

And after a football game here Sunday, one of the two--Erik Kramer of the Detroit Lions or Mark Rypien of the Washington Redskins--will be going to the Super Bowl.

Improbable?

More than that. But the inconceivable of 1991 is the reality of 1992.

Kramer has come the furthest--leaping in 12 months from the unemployment line to a place in the NFC championship game--but Rypien’s progress has been almost as spectacular.

All through his spotlighted 1991 season, Rypien’s passes were suddenly and regularly on target as the Redskins carved out a 14-2 record, the league’s

finest.

Nobody knocks him any more. The league is sending out some of its most famous and talented quarterbacks this weekend--starting with Jim Kelly and John Elway in the AFC championship game--and Rypien, as they say, makes three.

The outsider in this distinguished company, the guy who never dreamed last year that he would be ranked with Kelly, Elway and Rypien, is the Detroit quarterback, Kramer, whose team doesn’t seem to belong, either.

How did Kramer get here?

Not as a Potato Bowl star, that’s certain.

“We blew the Potato Bowl,” he said this week, talking about a mid-1980s junior college game for the national championship, when Kramer led L.A. Pierce against Taft College. “I threw four interceptions.”

Nor did the Lions groom Kramer in 1990 for his 1991 role as their starter. During the 1990 season, after two unproductive years in Canadian football, Kramer was on Detroit’s injured-reserve list--merely hanging around, in other words, in case injuries struck down the club’s veteran quarterbacks.

When the Lions got through the season without him, they cut him. That was a year ago this month.

“I went down to Atlanta and talked to the Falcons, and also the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, but nothing came of it,” Kramer said.

Then he got a break. The Lions, making training-camp plans, needed another arm to keep from wearing out Rodney Peete, their No. 1 quarterback, and No. 2 Andre Ware, the 1989 Heisman Trophy winner.

When they couldn’t find a better passer than Kramer, they re-signed him as No. 3 before their spring mini-camp 10 months ago.

“Erik had something,” Detroit Coach Wayne Fontes said. “He had a way with the (run-and-shoot offense).”

In the exhibition season, Kramer quietly moved past Ware, becoming No. 2.

And when Peete was injured in late October, Kramer inherited No. 1. In that role, he took a run-and-shoot team to the championship of the NFC Central Division, ousting the Chicago Bears.

Said Detroit receiver Mike Farr: “We knew that Erik could play all along.”

That’s more than Rypien’s Washington critics knew about him last September, when he started his sixth Redskin season. The club had stashed him on injured reserve in 1986 and again in ‘87, then watched him fumble and stumble from 1988 through 1990, throwing as many as five interceptions a game.

“(The critics) were basically right about me,” Rypien (pronounced RIP-en) said. “But I worked to get better.”

Their work ethics link Rypien and Kramer.

“When (the morning TV show) calls for Erik, you know where to find him,” a Lion executive said. “He’s in in the weight room.”

As NFL winners, Rypien and Kramer are also similarly poised and self-confident, as well as popular with their teammates. But they don’t appear much alike.

At 6 feet 4 and 230 pounds, Rypien, 29, a lightly regarded sixth-round draft choice from Washington State, could be a linebacker.

He and his wife Annette, a former Redskin cheerleader, are the parents of two daughters.

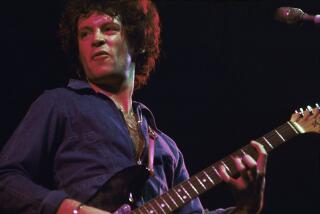

Kramer, 27, is listed at 6-1 (he is probably shorter) and 195 pounds (he is probably lighter). A free agent from North Carolina State, where in 1986 he was the Atlantic Coast Conference player of the year, he is curly-haired, fresh-faced and boyish.

He and his wife Marshawn look like two college kids off to a movie.

Rypien began life in Calgary, where his father was a cash register salesman.

“I played hockey before I played football,” he said, adding that the family moved to Spokane when he was 5.

Kramer was born in Encino and spent his boyhood in Canoga Park. He played high school football at Burbank Burroughs, then spent two seasons at Pierce.

At $200,000 a year, Kramer is the lowest-paid starting quarterback in the league--a spot Rypien held last season, when he made $300,000.

This season, with bonuses, Rypien will make about $1.5 million. He won’t be in Kelly’s neighborhood ($2 million), or Elway’s, even if he beats one of them in the Super Bowl on Jan. 26.

If he is the next NFL champion, Rypien can point to the improvement in his sack record--and his consequent injury-free status--as the main reason. Rarely clobbered this season, he escaped injury for the first time as a pro.

He was sacked only nine times, not because the Redskin line blocked any better--in the Joe Gibbs era it has always blocked well--but because Rypien finally learned to throw the ball away at the first sign of trouble.

For example, he beat Dallas quarterback Troy Aikman in the first Cowboy game this season, 33-31, largely because most of Rypien’s incompletions went into the first or second row, whereas Aikman repeatedly was hit in the Dallas backfield, before or after throwing.

“I’ve gotten smarter,” Rypien said, explaining one of his few injury-free seasons since high school.

Flipping the ball aside prematurely, rather than belatedly, helps Redskin morale enormously, he added, in two ways:

--”It demoralizes the (other team) if they don’t get anything for a (pass rush) but an incomplete pass.”

--”Your offensive linemen can (brag about the few sacks).”

Not much else is really different about the 1991-92 Rypien. When he came into the league, he could throw the ball 60 yards with a light touch. When he came up, he had that 131 IQ. He has always been as tough as Aikman--he has simply given up trying to prove it.

With his new attitude toward sacks and preventable injuries, Rypien rose to lead the league this season in a key statistic, the ratio of touchdown passes (28) to interceptions (10). He completed 249 of 421 passes for 3,654 yards.

As a pro, Kramer, by comparison, is merely getting under way. In eight starts, he completed 136 of 265 for 1,635 yards. His touchdown-interception ratio: 11-8.

The statistics, however, don’t tell it all about Kramer, who is on the charts as a second-year quarterback, although, in NFL-game experience, he is a rookie. The thing for Redskin opponents to fret about is that Kramer is doing more than Kelly, Elway, Rypien or other pro starters could at a comparable NFL stage.

Elway’s team at this stage lost in the first round of the playoffs. Rypien didn’t even get there. And Kelly was in the USFL.

“It’s just phenomenal what Erik has done,” Detroit tackle Lomas Brown said.

And, possibly, that’s an understatement.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.