‘Citizen Kane’ Still a Monolith on American Movie Screen

- Share via

“Citizen Kane,” usually trumpeted as the greatest American movie ever made, didn’t even win the Oscar for Best Picture.

That distinction fell to “How Green Was My Valley,” John Ford’s sentimental crowd-pleaser about a Welsh coal mining family. The Academy reflected the opinion of the day, that “Citizen Kane” was special, but somehow too different, too provocative.

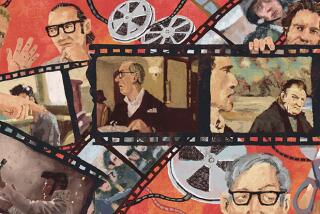

Orson Welles’ debut film eventually found a pedestal as cooler, braver heads determinedly raised it up. Looking back, that 1941 Oscar snub was just another of the controversies that have marked this movie’s history.

“Citizen Kane,” which begins the Saddleback College/Edwards Cinemas classics series tonight, has always shouldered both greatness and controversy.

The story about Charles Foster Kane, a hugely powerful newspaper publisher, was seen as a barely disguised attack on William Randolph Hearst, creating both political and professional problems for Welles throughout the early part of his career.

Years later, even Welles’ impact on the film was questioned. In two separate essays, critic Pauline Kael argued that screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz and cinematographer Gregg Toland were at least as responsible as the 25-year-old Welles for the brilliance of “Citizen Kane.”

That’s the kind of analytical dance that intrigues and amuses but, in the end, does nothing to diminish the film’s influence. It really is a monolith on the American movie scene.

Other pictures may be more popular (“Casablanca” and “Gone With the Wind” can bring a bigger smile to some fans), but “Citizen Kane” is unsurpassed.

What turns critics on is its cinematic promise. What Welles and his collaborators did was expand the possibilities of film while maintaining a distinctly American appeal.

It takes a tale of the American dream ruined by folly and avarice for a canvas, then uses bold technique to turn that canvas into something unique.

The opening sequence is fascinating: The phantasmic setting of Kane’s shrouded retreat, Xanadu, looking like a haunted house on an alien landscape, creates a fatalistic tone that stirs just below the movie’s surface.

But the picture, even with its portent, is never oppressive. “Citizen Kane” is, as Kael pointed out, perhaps the most fun of the great movies to watch.

In part, the film’s pleasure comes from mystery. Kane’s dying word, “rosebud,” sets a reporter on an odyssey to find out who or what rosebud was. As the reporter tries to grasp the slippery truth, we find glimpses into what formed Kane’s life. The revelation that something as mundane as a beloved sled played such a big role in that life rings with a poignancy in the movie’s summation.

The fun also comes from Welles’ infectious joy at exploiting the medium; his creativity has such a cocky glee that it’s as if he’s winking at the audience in every important scene.

It’s hard to pick just one example, but the craftiness of the revolving montage that describes Kane’s deteriorating first marriage is prime.

The utility and assurance of Welles’ ability to characterize how they’ve changed toward each other is seamless and terrifically ironic. We see them evolve from blushing lovers to wary domestic partners--a transformation that takes several years--in just a handful of seconds, all marked out by Toland’s whizzing camera, catching the actors in sardonic, sharply defining ways.

That passage, like so many others in “Citizen Kane,” provides insight.

It also provides the rush that comes from realizing how well art can mingle with entertainment, and that the movies may be the ideal place for such a union.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.