Bird’s Garden Party : Celtics Make It a Magical Night for Larry Legend

- Share via

BOSTON — It wasn’t a farewell, but an event for the ages, as the Boston Celtics threw a retirement party Thursday night for one of their own, a transplanted guy from rural Indiana named Larry Joe Bird.

Officially called, “Larry Bird Night,” the ceremony was a combination of Celtic pomp and circumstance, the basketball equivalent of a Kennedy wedding. But in keeping with the Bird persona, it also included blue-collar tributes from fans and former teammates and coaches.

Bird-mania transfixed this sports-crazed town as the date grew near. The Boston Globe published a special section on Bird thick enough to pin an arm to the ground. Commemorative T-shirts sold for $15.50. Autographed photographs of Bird sold for $245. Larry Bird Limited Edition Coins, complete with an easy payment plan, went for as much as $995. Autographed plaques had $139 price tags. The retirement party had become a cottage industry, but in this case, all the net proceeds from the sales went to the Celtic charitable foundation, of which Bird is a key member.

If you couldn’t secure one of the 14,890 seats available for the night’s festivities, scalpers were more than happy to part with a ticket--for up to $500, depending on the location. According to Steven Riley, the Celtics’ vice president of sales, Larry Bird Night was the toughest ticket to get since the seventh game of the 1984 NBA finals.

Maybe the Garden isn’t The House That Bird Built, but at the very least, he strengthened its foundation. So pathetic was the franchise before Bird’s arrival in 1979, that team officials used to sneak over to Fenway Park during Red Sox games and place Celtic season-ticket applications under each car’s wiper blades.

It didn’t work, but Bird did. By the end of his rookie year, season-ticket sales had increased from 4,800 to about 10,000. Suddenly it didn’t matter if you had one of the 1,000 obstructed view seats or if you were forced to watch from rafter’s edge. A glimpse of the great Bird was better than no glimpse at all.

This is the building where Bird led the Celtics to three NBA championships, which is all that ever truly mattered to him. Anything less was so unfulfilling, so . . . ordinary. But not to worry. During the Bird Era, the place almost always reeked of the smell from Red Auerbach’s championship stogies.

It was on the parquet floor that Bird earned every penny of his salary, from the $650,000 paid to him during his rookie season, to the $2.1 million he made last year. He wouldn’t have it any other way. It was on that court that Bird earned a legacy and a nickname: Larry Legend . Perfect.

Bird had insisted that if there were to be such a ceremony as the one Thursday--and mind you, he had to be convinced--it would and should take place only at the magical, rat-friendly, ancient Boston Garden.

After all, this is where he made his professional debut, getting 14 points and 10 rebounds against the Houston Rockets. It is where he fought with Julius Erving. Where he left bits and pieces of himself on the ancient wooden floor. Where he celebrated. Where he ached.

In the oven-roasted heat of the Garden in 1984, where the Lakers and Celtics played Game 5 of the NBA finals in 97-degree temperatures, Bird scored 34 points (15 for 20 from the field) and collected 17 rebounds in the victory. The Lakers gasped for oxygen, referee Hugh Evans collapsed from dehydration. And Bird? He flicked the sweat from his brow, as if he were born to play on hell’s court.

The Garden was basketball home to Bird. It was safe, familiar, lovable. He did not leave it without first making sure there were enough moments to treasure. Even last year, when his back throbbed with pain and retirement was a disheartening reality, Bird did what he could. In a March 15 game against the Portland Trail Blazers, he scored 49 points and had 14 rebounds as the Celtics won in double overtime.

There was no shortage of basketball dignitaries Thursday night. An hour before the ceremony began, Auerbach stood near one of the Garden’s entrances and puffed gently on a cigar as he answered reporters’ questions. This was an evening for him to cherish, an affirmation that the Celtic family he helped create and nurture was anything but myth.

Nearly every notable former Celtic player or coach was there: M.L. Carr, Don Chaney, Satch Sanders, Jo Jo White, John Havlicek, Bill Fitch, Scott Wedman, Rick Robey, Bill Sharman, Ed Macauley, Frank Ramsey, Gerald Henderson, Quinn Buckner, Tom Heinsohn, Tiny Archibald, Bill Walton, Dennis Johnson, K.C. Jones, Jerry Sichting, Artis Gilmore, Rick Carlisle and Dave Cowens, among others. Even Cedric Maxwell, traded away and bitter over the dismissal, returned to pay tribute to Bird. In fact, Maxwell was the first former Celtic to respond to the invitation.

Bobby Orr, the former Boston Bruin great, was at the Garden, too. It was Bird’s habit before every home game to stare up toward the rafters as the national anthem was played. From those rafters hung Orr’s retired jersey number. Bird used it as inspiration.

Now Bird’s number joins Orr’s number high in the Garden heavens.

At 7:35, Dave Gavitt, Celtic vice president of basketball operations, welcomed everyone to the proceedings. It was the beginning of an evening to remember.

The first standing ovation of the night was reserved not for any Celtic figure, past or present, but for Bird’s mother, Georgia. Asked by emcee Bob Costas to comment on her son, she would say only, “He was a great little boy.”

The crowd rose to its feet a few minutes later and began chanting, “Lar-ree, Lar-ree,”, when Bird made his entrance from a corner tunnel. He had changed from his dark, double-breasted suit worn during a pre-ceremony news conference to familiar white Celtic warm-up attire. It fit the moment.

Seated on a stool at center stage of the Garden floor, Bird acknowledged the audience with shy nods and waves.

“It seems like a perfect night, except for the fact that Bill Laimbeer (a longtime Bird antagonist with the Detroit Pistons) couldn’t be here,” Costas said. “What would you tell him if he were here?”

Said Bird: “That we would probably hang him up with (the banners).”

Former players and coaches were introduced. Video highlights of Bird’s high school, college and pro career were shown on huge screens positioned inside in the arena. After each segment, Bird would reminisce.

On the best advice he received as a Celtic: “Dave Cowens told me, ‘Don’t go about it 90, 80%, because the fans know basketball here.’ ”

On the 1985-86 Celtics, winners of the NBA championship: “The best team I’ve ever seen in the league.”

On the 1984 NBA finals game against the Lakers in the broiling Garden: “To the Celtics, it wasn’t that hot.”

There were stories shared and lots of laughter. Maxwell recalled the first time he faced Bird in practice and watched helplessly as 20-foot jump shots kept snapping the net.

“I’ll always remember thinking, ‘Boy, this white guy can play, can’t he?’ ”

NBA Commissioner David Stern said he was already counting the days until Bird and Magic Johnson are inducted into the league’s Hall of Fame.

Carr waved a towel and then, after tossing it to Magic, reminded him of the famous 1984 Sweat Game, when on-court temperatures reached 97 degrees.

“All I remember was Kareem Abdul-Jabbar with an oxygen tank to his face,” he said.

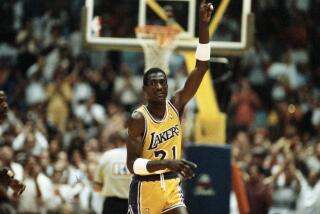

But some of the evening’s most treasured moments came after Magic, who also shed his suit in favor of Laker warm-ups (with a Celtic T-shirt underneath), took his place on the stage. Returning the favor when Bird attended his retirement party in Los Angeles last year, Johnson presented his friend with a framed piece of the Forum court. He also brought other gifts, mainly golden memories.

“You know, you caused me a lot of sleepless nights,” said Johnson, shortly after receiving a two-minute standing ovation from the Garden audience.

It was an ironic comment, considering that Bird has recently confessed that he still dreams about basketball--and that Johnson is almost always in those dreams.

Johnson remembered the Logan Airport baggage man who used to yell, “Magic, Larry’s going to get you tomorrow.” He remembered that he truly feared only one player: Bird. “Because this man would find a way to win that damn game.” He remembered the trash talking done by Bird and how each time Bird would back it up.

And then he chastised Bird.

“You told me one lie, only one,” Johnson said. “You know what that lie was? Larry Bird said that there will be another Larry Bird. Well, Larry, there will never, ever, ever be another Larry Bird.”

Bird and Johnson hugged, but not before Magic said: “I love you. I respect you. I admire you.”

Jerseys were exchanged. The Laker jersey Johnson presented to Bird read: “To the greatest basketball player ever, but more importantly, a friend forever.”

There were more video highlights shown. Then Auerbach paid homage and confessed a secret.

“The only regret I have, I never coached him,” he said.

At last it came time to raise the banner. Holding his young son Connor in one arm, Bird and his wife, Dinah, tugged on a rope and pulled the banner into place. Auerbach pulled on the other side.

A spotlight was placed on Bird and on the banner, which bore his No. 33 next to Dennis Johnson’s No. 3. There it now rests, between the 1986 NBA championship banner and the second of three banners that feature the other 16 retired Celtic numbers.

Again, more chants of, “Lar-ree, Lar-ree.”

Bird returned to the stage and addressed the audience. Occasionally his remarks were interrupted by cries of, “We love you, Larry,” and “Thank you, Larry.”

Bird spoke of Celtic pride and a Boston career that spanned 13 seasons. He told the crowd he would miss them and half-apologized for leading the Celtics to only three NBA championships. He thought they could have won five.

His voice rich with emotion, Bird said a final farewell.

“I say good night, Boston, and may God bless each and every one of you,” he said.

In his autobiography, “Drive--The Story of My Life,” Bird wrote that his career would end the same way it began: on his terms, according to his timetable. A fickle and oft-injured back wouldn’t allow him that luxury, forcing him to retire two, maybe three years before he had planned. But he did get one wish.

“When the time comes,” Bird wrote, “I just want to be able to walk out on that court one last time and say, ‘Thank you.’ ”

So he did. And a city, forever touched by his pride, his skills, his love of being a Celtic, said thank you back. It was the least it could do.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.