POP MUSIC REVIEW

- Share via

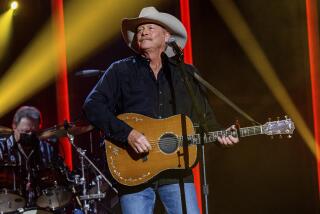

ANAHEIM — In a gesture of unparalleled daring for a mainstream “new country” performer, Alan Jackson on Thursday night sang “Working Class Hero,” his own routinely sentimental paean to the virtues of a lifetime of honest labor, then immediately followed it with a clenched reading of John Lennon’s acerbic, profanity-spiked classic of the same name.

“A working class hero is something to be,” Jackson intoned in a biting voice that was at once a snarl and a wince. He capped the song’s grimly tolling refrain by flinging his white cowboy hat to the floor. The crowd at Anaheim Arena was stunned silent. Before he finished, this tall, handsome star, who has seen all three of his albums sell in the millions, added a bitter verse of his own about the flight of good jobs from the American economy.

“A working class hero really doesn’t have a chance in this country any more,” the Georgia-bred Jackson softly told his still-hushed fans after he had finished singing. “I wrote my ‘Working Class Hero’ song about my daddy, and to me he’ll always be a hero. But there’s another side to the story, and I thank John Lennon for helping me bring it to you. ... “ All right, so a pop critic’s sweet dreams are made of slightly different stuff than Patsy Cline’s.

In waking reality, Alan Jackson didn’t rock the jukebox Thursday, much less rock the boat. This was an electronically glitzy but otherwise bland performance by a star whose success is predicated on pleasantly catchy, mildly witty material that never seeks to dig beneath the surface of everyday human interactions, let alone tackle anything controversial.

Jackson let the video cameras in front of him and the two screens behind him do all the real work in this walk-through of a concert. The crowd loved it, too, saving some of its biggest cheers for video close-ups of his face, and especially for a slow pan up the back side of his blue jeans.

Video cheesecake shook and slithered suggestively behind Jackson during “She’s Got the Rhythm (And I Got the Blues).” That got a real rise; Jackson deserves a special marketing award for getting rid of the boring old images of honky-tonk culture that the song’s lyric suggests, and substituting “Flashdance” routines done in cowgirl chic. The Al-goes-waterskiing-in-his-cowboy-boots video sequence during “Chattahoochee” also had ‘em whooping.

In fact, there was no dancing, no kinetic action during this show. It was just movies, starting with a video introduction that, in an incredibly crass move, was really just a thinly disguised beer commercial for Jackson’s tour sponsor. It’s not enough that they get to hang their banners all over the place?

Jackson’s band was proficient, especially Danny Groah on guitar, but you can’t expect players to try anything adventurous when the man they back is incapable of doing so himself. Jackson’s voice, which is nice, but hardly distinctive, sounded thin through most of the dull early going and midsection of the 75-minute (including beer commercial) concert.

He gained some punch during a closing stretch of lively, chunky-rhythmed hits. It began with “Don’t Rock the Jukebox,” which featured a visual element that was live, rather than video-generated: a ludicrous, 20-foot inflated model of a Wurlitzer jukebox that bounced insipidly behind the band throughout the song, like Barney reincarnated as a coin-op machine the size of a triceratops.

“Chattahoochee” (the water sports number) and “Mercury Blues,” decent rockin’-country songs from Jackson’s current album, “A Lot About Livin’ (And A Little ‘Bout Love),” closed the show on an energetic note.

Jackson does have a sincere regard for traditional country sources. He took a stab at a traditional gospel-bluegrass number. Amid curtains of stage fog and the kind of fancy, swirling light show you expect from Genesis, he invoked the ghost of old Hank in the spooky ballad, “Midnight in Montgomery.”

He also tried to sing some old Hank, covering “Mind Your Own Business.” The thing about old Hank, and most of the other country greats, is that there is something wild or haunted that comes across in their music. Listening to Williams, you believe he could drunkenly pop you in the nose, or worse, if you didn’t mind your own business. Jackson’s tame reading intimated no such risk.

Jackson pretended he was being daring when he introduced a just-written, unrecorded number: “We have never played this thing. I’m just crazy to get up here and do it for you all.” Who was he kidding? The tune, “Let’s Get Back to Me and You,” involved a handful of chords and a standard mid-tempo beat. Good country bar bands take on tougher assignments each night winging requests for tips.

The enthusiastic response to Jackson’s video substitutions for in-the-flesh effort (fans even cheered the beer commercial) suggests that we had best cherish musicians who generate excitement in real time while they are still around.

If video backdrops can be perceived as a more alluring in-concert element than what is actually taking place on stage, the days of the pure live performer may be numbered. In that respect, at least, the videogenic Jackson can claim to be in the vanguard.

As bland between songs as during, Jackson did pause to pay fitting homage to his opening act, John Anderson.

This huskily-built Floridian came on the scene in 1980, and has stood since as one of the most distinctive voices in country music. Unless you count his bright blue, sequined stage jacket, there was nothing flashy about Anderson.

But that voice, with its cottony, gently bending drawls and muted cries, was capable of suggesting both the ache and enjoyment of lived experience. It alone was enough to hold a listener, and the material was frequently worthy of Anderson’s singing.

His band was excellent: fiddler Joe Spivey shone throughout, guitarist Vernon Pilder did a pretty fair Mark Knopfler approximation on the Knopfler-penned “When It Comes to You,” and Darrell DeCounter’s R&B-style; organ helped key a hard-rocking “Swingin’.” Anderson strapped on a banjo midway through the set and plucked it nimbly as he led the band through a couple of bluegrass-style instrumentals.

He banged out 16 songs in just under an hour, pacing the set with plenty of variety. It ended with a moving rendition of “Seminole Wind,” the title song of the 1991 album that put Anderson back on track commercially after a long fallow period.

One of the best country songs of recent years, it is a haunting, eloquent, darkly surging lament for the bulldozing of nature in Anderson’s home state. It’s the equal of anything mustered by rock’s enviro brigade of Greenpeace backers and Walden Pond preservers, and it won Anderson a standing ovation. It goes to show that if you give people something worth chewing on, they will savor it.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.