A Scrabble Shark as Good as His Word

- Share via

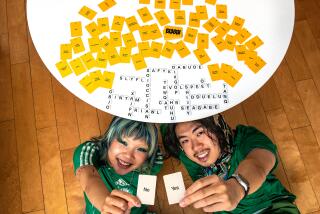

There are two kinds of Scrabble players--people who play a friendly game and real players who want to tear their opponents’ hearts out, even as they earn 50 extra points for using all seven of their letters.

As to my own approach to the game, let me confess that at some point during his adolescence, my son stopped playing Scrabble with me and his father because the lad hates blood sports.

He seems to think, in spite of years of watching his parents play, that board games are supposed to be fun, not occasions to nuke your enemy--that is, anyone who dares to play against you--with your superior vocabulary and superb strategic skills. Go figure.

The third Tuesday of the month is Scrabble night at the Barnes & Noble bookstore in Northridge. Predictably, four Scrabble stalwarts showed up recently in spite of a driving rain.

The Northridge store isn’t fancy-schmancy like the one in Encino--it lacks a Starbucks, for one thing. But the management goes all out for its Scrabble players, supplying them with deluxe versions of the 63-year-old game (complete with turntables), Scrabble dictionaries and enough candy, tea and coffee to keep them keenly alert as they calculate how many U’s are still out and other things that only Scrabble players care about.

In case you grew up on a distant star, Scrabble is the trademarked and copyrighted word game in which letter tiles, given numerical values from 1 to 10, are used to form interlocking words, crossword fashion.

Manufactured by Milton Bradley, the game seems to have been around as long as crayons and lunch boxes, but, in fact, it only became wildly popular in the mid-1950s. (Let me assure you that, “Ozzie and Harriet” notwithstanding, girls who could beat their boyfriends at it, did.)

Some 33 million Americans play the game, more than 10,000 seriously enough to have joined clubs affiliated with the National Scrabble Assn.

*

At Barnes & Noble on the sodden night in question, two pairs hunch over tables set up between rows of books. At one, a man and a woman play. She is a statistician. He doesn’t want to reveal his occupation, but let’s just say that he tried very hard to find an S on the board so he could lay down C-U-R-E-T-T-E.

Scrabble players are nothing if not verbal. Bobbi, one of the two women at the more loquacious table, spells her last name for me: “Z as in zany, I, T as in toenail, O as in Orenthal.” You get the drift.

“We’re not cutthroat,” Zito and her partner, Eva-Lynn Ratoff, declare. As they see it, the statistician and the man who knows what a curette is and how to use one, they’re cutthroat.

As were two women who once surfaced on Scrabble night, to the horror of Zito and Ratoff. “They were Scrabble sharks,” Zito recalls. Janice Kent, the store’s community relations coordinator, remembers the pair and is even harsher in her evaluation. She resorts to the universal language of Laudromats to find a metaphor pungent enough to capture the mean-spiritedness of the “Scrabble sharks.”

“They were,” she says, “the kind of women who take your laundry out before it’s dry.”

Kent herself is a good person, according to Zito and Ratoff. Once, Zito recalls, Kent told some of the better players that whether they wanted to or not, they had to play with a hapless woman who couldn’t quite master the rules of the game.

Zito says of Kent, with only the teeniest bit of sarcasm, “She’s the Mother Teresa of Scrabble.”

For all their vaunted lack of ferocity, Zito and Ratoff don’t want you to get the wrong idea. They may not be Scrabble great whites, but they’re not Scrabble weenies either. “We’re not such nice guys that we want to give each other triple-letter scores,” Ratoff says.

She wins their first game, 278 to 248.

Then, as in a spaghetti Western, the Mysterious Stranger appears.

Geoff, not his real name, is a writer who lives in the West Valley. To support his passion, which is writing fiction, he ghostwrites. The worst of that odd profession, he says, is going to parties with people whose books he’s written and hearing them say, “My new book is coming out soon.”

“It’s an interesting use of the word my,” Geoff notes. In his non-writing life, Geoff is a serious Scrabble player, playing several times a week against human or computer.

*

How serious? Geoff once managed to parlay O-B-L-I-Q-U-E, laid in the right place on the right board, into “170-something points.” He routinely scores more than 500 points when playing Scrabble with one other player. (The record of 770, in tournament play, was set by Mark Landsberg of Los Angeles.)

To give you an idea of how rabid a Scrabble player Geoff is, he lied to his girlfriend to be at Barnes & Noble this night. She wanted him to go out to dinner with her and her bosses. He said he had other plans.

His plans were to see if he could pick up a game. He gets antsy if he goes too long without casting some less-able opponent into the depths of Scrabble hell.

Geoff sits down with Vito and Ratoff and plays his opening gambit, K-A-I-D-S, for 30 points.

“What is it?” one of the women asks.

“A Muslim something,” Geoff answers.

“Omigod,” Ratoff sighs. “What do you do?” asks Zito.

“I go around from bookstore to bookstore, hustling Scrabble,” Geoff replies.

In fact, Geoff is what we in Scrabble circles call a mensch.

He takes it upon himself to make sure his word is legit by checking it in the Scrabble dictionary. Claiming words are real when they are not is a time-honored Scrabble tactic, called, simply, bluffing. The rule is that, unless your fellow players challenge your word and find you out, bluffing is OK.

Neither Zito nor Ratoff challenged, but K-A-I-D-S is not in the Scrabble dictionary. The word Geoff was thinking of was C-A-I-D-S, meaning Muslim leaders. Geoff manfully withdraws K-A-I-D-S and lays down M-A-S-K-E-D for 32.

“We’ve never played with someone with that kind of integrity,” Zito says.

“We’re screwed,” adds Ratoff.

Geoff points out that the best way to become a great player is to play with people who are better than you, opponents who make you stretch. He offers some pointers. There is a three-letter word that is all consonants (C-W-M, a “cirque,” or walled basin) and a three-letter word that is all vowels (E-A-U, “water”).

The women do their best. Zito adds all seven of her letters to the existing word, Q-U-A-D, to make Q-U-A-D-S and S-A-L-U-T-E-R. She gets 75 points, including the 50 bonus points.

“It’s not enough,” she moans. “That’s pathetic.”

The women have just a letter or two left and are trying to find a place on the board to put them. Ratoff wants to unload a T and an A. Geoff graciously advises her to add them to a U that’s already on the board.

U-T-A “is a French something,” he counsels.

Actually, it’s a large lizard, but in Scrabble, what a word means is never as important as what it’s worth.

Needless to say, the evening’s Scrabble prize goes to Geoff, who manages to score a highly respectable 298 against the pair. It’s a Barnes & Noble tote bag with a picture of William Shakespeare on it.

And it was Shakespeare, wasn’t it, who said: “A rose by any other name is worth three times as much if you put it on a triple-word score”?

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.