Casting a Long Shadow Over Films

- Share via

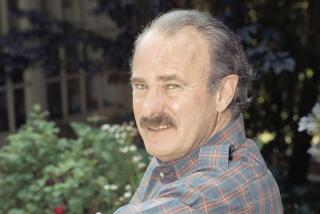

For a guy who can see eye to eye with an NBA player, actor James Cromwell is not an imposing figure. Even at 6 feet, 7 inches, his gentle manner, soothing voice and caring smile put him more in line with Mr. Rogers than a power forward.

These are qualities Cromwell brings to his latest film, “The Education of Little Tree,” which opens today, and ones he alluded to in “Babe,” the film that earned him an Academy Award nomination in 1996.

But Cromwell is no one-note actor, as his role in “L.A. Confidential” attests. As a brutal, 1950s-era police captain, he liberally smudges the line between good guys and bad guys.

“It’s always fun to shoot Kevin Spacey,” said Cromwell, with uncharacteristic glee, a reaction more befitting the “L.A. Confidential” cop than “Babe’s” Farmer Hoggett. But then, it was Spacey who walked off with the supporting actor Oscar in 1996 (for “The Usual Suspects”). Revenge is sweet, even on celluloid.

Curtis Hanson, writer-director of “L.A. Confidential” (which recently racked up best picture awards from L.A., New York and Boston film critics and the National Board of Review), said that the Cromwell-Spacey face-off was merely coincidental. He wanted Cromwell, he said, because the actor exudes “great gravity, yet there’s that twinkle in his eye.”

What Cromwell did so well in the part, Hanson said, was to “get into the complicated relationship between the public and their police. We want security and protection, but we don’t want to know how he does it. [Cromwell] has that paternal strength, but at the same time, he has a danger about him.”

Perhaps it’s the gravity, coupled with his passion to live in a society where people do the right thing, that has on occasion gotten Cromwell into trouble. At the urging of his acting coach, he repaired some of the bridges he scorched earlier in his career.

“I don’t like to talk about acting,” said Cromwell, 57. “This whole process of getting a job in this town, the idea of going into a room after you’ve been at it for 30 years, to audition with some people who just managed to get out of business school. . . . You tend to project a certain amount of hostility, which is the last thing that they are interested in dealing with, especially when you’re as big as I am.”

Cromwell likes to say that his “careen” through film, stage and television work became a “career” with his Oscar nomination. Since then, he has appeared in Oliver Stone’s “The People vs. Larry Flynt,” “Star Trek: First Contact” and “L.A. Confidential.” Next year he’ll be seen in “Species II” and “Deep Impact.” There are also two sequels to “Babe” in the works.

Though Cromwell is as happy as a pig in mud over the success of the first “Babe,” he didn’t exactly go hog wild for the script. He had just returned from New York, where he made a film and appeared on Broadway in “Hamlet,” when he received the “Babe” script. “I looked at it and thought, ‘This is ridiculous, this is a little Disney kiddie film, and besides that, there’s no dialogue.’ ”

In what he now calls the “most important choice in my career,” he decided to add “pig farmer” to his credits.

“I chose to go down there, show up every day and . . . whatever it was that they wanted to accomplish, I was going to do it with good humor and all the talent that I could bring to it.”

Originally, Cromwell didn’t plan to be an actor; he wanted to be a hockey player or design sports cars. But as a young man on location in Sweden with his father, the late director John Cromwell, he decided to give acting a try. “It was an opportunity to emulate my father, whom I was very proud of,” he said.

If there was one constant in his careening early career, it was his tendency to champion controversial causes. In the 1960s, Cromwell joined civil rights marches in the South, fought for the release of imprisoned Black Panthers in the North and, after the Kent State killings, helped start a guerrilla troupe that presented politically charged improvisational theater.

But Cromwell wasn’t exactly weaned on activism. He was born in Los Angeles and grew up in the suburbs of New York. “As a little boy, I went to a prep school. . . . I didn’t know anything about Mississippi and I didn’t know what the hell [racism] was.”

His initiation was the Free Southern Theater, which performed for black audiences in rural Mississippi. Cromwell, oblivious to the implications, was given a crash course in racism when the actors were chased by angry white Southerners.

“They didn’t take us very seriously, though,” Cromwell said, “because we were doing ‘Waiting for Godot.’ I think the [Ku Klux] Klan thought we were sort of a joke.”

Eventually, Cromwell’s friends became accustomed to his incessant chatter about human rights. He was frustrated because he didn’t know how to turn the talk into action. Since he’s become known for his acting successes, he’s found a way. “Finally,” he said, “I’m in a position to be of use to the organizations that I believe in.”

One of those organizations is Walking Shield, which provides housing, medical care, educational supplies and food to Native Americans.

In his latest film, “The Education of Little Tree,” Cromwell plays a Scotsman who lives in Tennessee’s Smoky Mountains during the Depression and is married to a Native American. The couple tries to raise their grandson (played by Joseph Ashton) to respect the Earth and understand his Indian heritage. “Little Tree” is an independent picture produced by Jake Eberts and distributed by Paramount, written and directed by Richard Friedenberg (“Dying Young”).

“It was an interesting set,” said Friedenberg, who made his feature directorial debut on “Little Tree.” “We had Jamie [Cromwell], who’s very involved in Native American activities; we had Tantoo Cardinal [as Cromwell’s wife], who is an extremely outspoken Native American; and Graham Greene, who is equally outspoken. . . . They were keeping me very accurate.”

Even though the film takes place in 1935 in a remote part of the country, the message, Friedenberg said, is universal. “It’s the story about the strength of family and the unconditional love that families have for each other, no matter how the families are made up.”

To Cromwell, among the most important messages in the film is that people are losing their connection to Mother Earth.

“The cost of this is that we have lost touch with the rhythms of the Earth . . . our obligations as stewards of the Earth and our sense of community and brotherhood.”

Also touched on in the film is that treaties were broken, that Native American lands were desecrated and that efforts were made to rid Native American children of their language and culture.

Cromwell, who likes the Danny DeVito approach to filmmaking, is planning projects that he can write, produce, direct or act in, through his own production company, Koshari Films (Koshari is a Hopi Indian name). He is working with his writer-actress wife, Julie Cobb (daughter of Lee J. Cobb), on one project in particular, a script Cobb is writing about a man who was responsible for prison reform in Australia.

In the meantime, Cromwell hopes that audiences will recognize “Little Tree” as a worthwhile, entertaining film, as they did “Babe.”

“That’s always the hope,” he said. “It’s the type of story that I want to be in as an actor, that I want to see as an audience member, that I don’t see get made often enough.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.