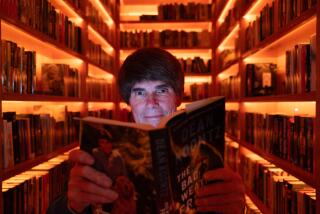

Koontz Veers From Evil to Realm of Good

- Share via

Dean Koontz’s suspense novels, a mix of schlock and brilliance, have always been driven by his curiosity with evil, and “From the Corner of His Eye” is no exception: Its villain, Enoch “Junior” Cain, is a serial killer. But Koontz has also shown an unusual interest in goodness--in how people can absorb evil’s blows and sometimes triumph over them.

This novel is his most religious yet. Through the mouthpiece of Tom Vanadium, an alloy of priest and detective, Koontz presents a full-blown theology based on quantum physics, in which “every human life is intricately connected to every other on a level as profound as the subatomic level in the physical world.”

This message, extrapolated for the purposes of the story, means simply: Good people care for others; bad people care only for themselves. It is a lesson basic to any mainstream faith.

By starting the story in 1965, Koontz implies that something besides Cain’s flawed nature leads him to push his wife, Naomi, off a 15-story fire lookout in the Oregon woods. The counterculture is egging him on. Cain reads self-help books that advocate helping oneself.

Later, living off a multimillion-dollar settlement for Naomi’s “accidental” death, he collects avant-garde art. Koontz sees this as another symptom of Cain’s sickness and uses it as an occasion to assail critics who prefer edgy, ugly, depressing art to the accessible, the beautiful, the uplifting. Which is somewhat odd for a writer who has made his name by scaring his readers, though understandable for a writer who craves respect to match his sales figures.

On the same “momentous day” as Naomi’s killing, two other stories begin--not, Koontz would say, by coincidence but according to the “strange order” that underlines the “apparent chaos.”

In a Southern California town, child-abuse victim and neighborhood benefactor Agnes Lampion gives birth to a son, Bartholemew, after a traffic accident in which her husband is killed. Barty is a prodigy who can read and write and sense the existence of parallel universes before cancer forces doctors to remove his eyes at age 3.

And in San Francisco, 16-year-old Seraphim White, a minister’s daughter who was raped by Cain in Oregon, dies giving birth to a daughter, Angel, who shares some of Barty’s remarkable powers.

Koontz connects these stories with his usual ingenuity. He has always had near-Dickensian powers of description, and an ability to yank us from one page to the next that few novelists can match. Thus, he can hold our interest as he explores mystical notions--that every day is “momentous” because our smallest acts of kindness or cruelty ripple to the ends of the universe, affecting people we may or may not ever know; and that our moral choices split us off from other universes where other choices have been made.

Aside from a secondary cast of eccentrics, Koontz’s characters are all good or all bad (just as his prose, if it were music, would be an unbroken fortissimo). In the past, we didn’t mind this too much. His villains were fascinating, and his heroes were drawn with enough homely detail so we could kid ourselves into believing they were folks just like us.

Cain is true to form. He’s too bad to be true, but the self-deluding forms his badness takes are persuasive. He thinks he’s “improving” himself as he descends from murder to murder and trades actual love for the wistful hope of it, useful work for idleness, contentment for panic, and good health for such psychosomatic illnesses as vomiting, diarrhea, hives and boils--like the plagues of Egypt. The loneliness of evil, which Joyce Carol Oates captured in her serial-killer novel, “Zombie,” is underlined again here.

Sooner or later, we know--because the tactics Vanadium uses in tracking down the killer have made Cain fear an unknown enemy named Bartholemew--the bloodstained killer and the little blind boy will come face to face.

But the excitement of their meeting doesn’t last after we close the covers, because Barty and Angel, even Vanadium, are not only too good to be true but incredibly so. If Koontz wanted to illustrate the radical interconnection of human beings, he might have been advised to keep those people and their circumstances as realistic as possible--no special powers, no shading into science fiction, just life as we know it. But how could he do that when his fans demand a thrill a minute?

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.