Fowled Away

- Share via

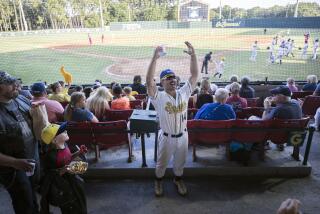

SALEM, Ore. — The Chicken is barking.

His breath comes in short, loud bursts, straining to escape the narrow opening in his foam beak.

He sprints through the warm night, off the faded field, into a windowless concrete storage room, plopping down on a folding chair.

Outside, in the aluminum bleachers that ring this tiny baseball stadium in the Northwest woods, the laughter dies.

Inside, the Chicken gasps.

“Was it funny?” he asks.

He tears off his costume head, swallows air in giant breaths, chugs a 20-ounce bottle of water, gulps more air.

His blue vest is stained dark with sweat. His yellow leotard is dotted with infield dirt.

His black hair is plastered to a face that is pale from nearly three decades of hiding. It is the smooth face of a boy on the thickening body of a man who next year will turn 50.

“Well,” he asks again. “Was it funny?”

Yes, he is told. It was great.

He looked devious throwing the water balloons at the first base coach. He looked helpless when players retaliated by showering him with their own water balloons.

He is told that many fans smiled, chuckled, held up little children and pointed them toward this strange and wonderful creature who has made this Saturday night so memorable

He frowns. That’s not what he asked. He wants to know about the roar. Where was the roar?

Nearly every summer night for most of his adult life, he has surrendered his identity and hidden his face and changed his voice in search of the roar.

Did he somehow miss the roar?

Outside, the inning is nearly over,

an expectant hush descending upon several thousand fans who have put down their Killer Kielbasas and Dippin’ Dots ice cream to watch what may

be the final webbed footsteps of a legend.

Inside, the Chicken growls.

“But was it funny????”

*

Put on the head.

Go ahead, pick up the one-pound clump of feathers and baseball-sized eyes and giant beak and put it on.

Feel what Ted Giannoulas has felt for 29 years.

Good luck enduring it for more than 29 seconds.

The inside of the head of the San Diego Chicken is sour, steamy, a moldy shower stall in a darkened locker room.

“First time I put it on, I couldn’t believe it,” said his sister Chris. “I thought, how does he do this?’ ”

And how does he see? The holes in the beak through which he views the world are only inches wide, like a couple of cracks in a Venetian blind. He cannot look below him, or above him, or beside him.

Put on the chicken head and realize, Ted Giannoulas has gone through life with the unique blessing of being exposed only to what is directly in front of his face.

He sees the children’s smiles. He doesn’t see the uncomfortable stares from those who watch him increasingly strain to create that joy.

He sees baseball in all its flannel-and-leather-covered romance. He didn’t see the game’s creeping selfishness and greed until it was too late.

Today, the most recognizable mascot uniform is no longer a uniform, but a time warp, one in which Giannoulas finds himself seemingly trapped.

He is the best-known, highest-paid baseball mascot in history, a star who still fills minor league stadiums and attracts autograph lines that stretch for blocks.

But for the first time, he did not work a major league park this season, because the big leaguers no longer have the time or the interest.

In the Chicken’s final days in major league clubhouses, players cursed him, ran from him, even purposely missed throws that might have hit him.

“It’s so sad, there’s such acrimony in there now,” Giannoulas said. “The players are way too cool. Guys who I had fun with in the minor leagues wouldn’t even say hello to me anymore.”

He is the father of modern sports entertainment, an accomplished vaudevillian who invented the art of toying with an umpire and dancing with a player.

But there are nearly a dozen imitators out there now, slick and hip traveling mascots with names like BirdZerk! and ZOOperstars!, acts that allegedly steal the chicken’s material and send him screeching.

“Few things stick in my craw, but this is one of them,” Giannoulas said. “Those laughs are my babies. My babies!”

While never missing an event in 29 years--more than 6,000 consecutive games--Giannoulas has thrilled three generations of children.

But he wakes up today at 49 with no children of his own because he never had the time.

“You know how everyone always says that if they lived their life over again, they wouldn’t change a thing?” Giannoulas said. “Well, that’s bull. I would change things. I would have given more time to myself.”

Observers agree his unique style of physical humor and mime would make Giannoulas a great entertainer on any stage.

But because he refuses to allow himself to be photographed outside of his suit, nobody would recognize him.

Twenty-nine years of standing ovations for the Chicken, and not once has anybody cheered Ted Giannoulas.

Twenty-nine years of fame, yet nobody has seen his face.

“Sometimes it’s like I don’t have a real life,” he said.

Unlike the owners of other mascot costumes, Giannoulas also will not allow anyone else to wear the suit and learn the trade.

“I’m not a department store Santa Claus,” he said. “There is only one Chicken.”

So when Giannoulas retires, the Chicken will disappear forever. Then what will happen to the man?

It is a question he faces daily, yet never really faces, still working more than 100 dates a year, hugging a happy child in Wyoming one moment, dealing with a jerky first baseman in Fresno the next.

Have you seen him? Do you remember your favorite gag?

Was it when he marched onto the field followed by a line of children dressed like baby chickens, a skit that ended with the kids lifting their legs on the umpire? Or was it when he lost a dance contest to a Barney look-alike, then punched him out?

He’s still doing the same things, only this summer, for the first time, one of his gigs was a softball tournament. And while the San Diego Padres hired a mascot to work one game at his home Qualcomm Stadium, it wasn’t him.

In serving baseball, the San Diego Chicken has become like baseball itself: a brilliant idea, born of innocence, bred with joy, but now struggling to age gracefully through a building cloud of impertinence and indifference.

“Ted invented mascots, he was the first and funniest, I have nothing but respect for him,” said Dave Raymond, who spent years wearing the costume of the popular Philly Phanatic. “But if you’re not careful, you can lose yourself in that suit.”

*

The Chicken is dripping.

Running off the field in 90-degree Fresno heat, he grabs for a towel as he drops to a chair in a humid tunnel behind the dugout.

As always, the head is the first thing to come off. But this time, because of a skit involving a special costume, he must also peel off the rest of his leotard and feathers.

“Can you help me take off my suit, sir?” he asks a team employee, gasping as he buries his exposed face in the towel.

The usher doesn’t understand.

The Chicken pauses, stares up, asks again, a little louder.

“Sir, please, can you help me get out of this suit?”

The employee shrugs and steps forward, grunting and grabbing and pulling and yanking and slowly stripping away the wet layers until the Chicken becomes a man again.

At which point Giannoulas, his face still in the towel, drops breathless back into his chair.

“I’ve seen him for the last five years,” whispers a nearby guard. “But I’ve never seen him like this.”

*

The search for the Chicken began earlier this summer during a meeting with a 5-foot-5, middle-aged man standing outside a budget hotel in Lake Elsinore.

He was wearing blue jean shorts, an untucked blue Hawaiian shirt and reading glasses propped on a full head of black hair. He looked like a tourist. He looked like a science teacher. He looked like anything but ...

“Ted Giannoulas,” he said, extending his hand.

He saw the surprised look on his visitor’s face. He shrugged. He is used to the disbelief. It really doesn’t matter. It’s never about him, anyway.

“I have plenty of Chicken stories,” he said. “I’m afraid I don’t have any Ted stories.”

Oh, but he does.

As the essence of baseball remains curiously timeless, so, too, does the man underneath its mascot.

The Chicken is a multimillionaire who commands in the neighborhood of $7,500 an appearance.

Yet Ted Giannoulas has lived in the same modest suburban San Diego house for 22 years.

This is partly because it is within a mile of the home of his mother, who still makes his costumes. This is also because the house is near a good library. After spending his summer chasing a roar, he spends his winters soaking in silence.

The Chicken is also an effective salesman who makes big money in affordable merchandising that includes everything from dolls to videos.

Yet Ted Giannoulas doesn’t have an ATM card. No pager. No personal e-mail address. Can’t use the computer printer.

When he arrives every night at the ballpark on his leased luxury bus--he hasn’t flown regularly for 10 years because of the hassle--he is not carrying a wallet, keys or a cell phone.

The Chicken is a perfectionist who carefully choreographs every move and understands every nuance. He knows the size of every minor league foul territory, the nature of every sound system, the location of every bathroom.

Yet when he talks to small children afterward in the autograph line, he uses the words and high-pitched tones of a character from Looney Tunes.

“Hey, Pork chop!” “Hello, Wiener!” “Howyadoin’, Sugar Cube?”

Folks say this is part of what makes the Chicken different--and more enduring--than other mascots.

The other ones don’t talk. They can’t talk. To open their mouth is to risk ruining the illusion by sounding different from the person who wore the costume the previous year.

Because the Chicken is the Chicken forever, he can talk, and so he does, cackling on the dugout, whispering to the children, and engaging in a running patter with fans in postgame autograph lines that often last past midnight.

Incidentally, he signs for free. He signs everything. He poses for anything.

On that summer night in Salem, seated at the head of a long line winding through the right-field playground, how he chirped.

“Have some Kentucky Fried Chicken!” announced one brave little boy, plopping down a trademark bucket on the autograph table.

“I hope that’s nobody I know,” said the Chicken, staring at the chicken.

“Thanks for helping us win tonight,” mumbled a shy little girl.

“I’m your good-cluck charm,” said the Chicken.

“Why did the chicken cross the road?” asked a couple of teenage boys.

“To get away from stupid questions,” said the Chicken with a laugh.

The question he is most often asked, of course, is a more basic one.

Is that really still him?

It is asked by adult fans who bring him 20-year-old autographs in search of comparative proof. It is asked by senior citizens who test him with questions about an act in El Paso in 1978.

In Tucson, the question stunned Giannoulas when it was asked by a man in his mid-20s who brought him a photo of the Chicken performing his trademark biting of a baby’s head.

“That baby was me,” said the man.

It is also a question increasingly asked by friends and family members.

Said Chris: “I’d like to see him finally relax and enjoy the fruits of his labor. After a while, you’ve got to say, maybe I should go home now.”

Said former mascot Raymond: “Can you imagine if he had decided to share his knowledge, to teach others his craft? He would be running the entire mascot industry today. He would be his own little Disney.”

Instead, the Chicken remains a huge man in a small world, unfolding eye charts for young umpires, literally stealing bases for old laughs, signing autographs that begin “Best Wishbones ...”

“He’s thought about retiring,” said his wife, Jane. “But how do you retire from yourself?”

*

The Chicken is crying.

All night in this tiny ballpark in Butte, Mont., people have told him that he must meet a boy named Matthew.

“Matthew is looking for you.”

“Matthew wants to see you.”

Late in the game, the Chicken is finally directed to the child, a 4-year-old with huge eyes.

“How are you doing, you little wiener?” the Chicken asks.

“I’m really enjoying you,” Matthew says.

“Having fun?” the Chicken asks.

“You are very funny,” Matthew says.

As Matthew tentatively reaches out to stroke the Chicken’s suit, his father leans over and whispers into Giannoulas’ ear.

“My son has been blind since birth.”

Giannoulas spends the rest of the game in tears.

“Imagine allowing a child to see with his ears,” he says later.

That night is what convinced him that, even after all these years, this is what he must do.

“That night,” he says later, “laughter was the most powerful force in the universe.”

*

His father never liked it. Up until two months before his death of lung cancer in 1979, John Giannoulas was not proud that his son was the Chicken.

Growing up the only son of Greek immigrants in London, Ontario, young Ted liked to rearrange the furniture, wear a cape and jump around like Mighty Mouse.

His father wanted him to stop clowning around.

“My husband wanted Ted to be a doctor, something big, something serious,” Helen Giannoulas said. “He was a very traditional Greek man.”

After third grade, Ted obeyed his father, turned his emotions inward, tried to become that model man.

“I always wanted to be the class clown, but I never had the nerve,” Giannoulas recalled. “So I would always sit next to the class clown.”

Until that spring afternoon in 1974 at San Diego State.

Giannoulas, a student, was sitting with other fellow workers at the campus radio station when an executive from a local rock station walked in and asked if anybody wanted to wear a chicken suit and pass out promotional eggs during spring break.

Nobody said anything. The executive looked at Ted.

“You’re the shortest,” he said. “You can start tomorrow.”

Eager for the money and pining for adventure, Giannoulas said yes.

“Sixty seconds that changed my life,” he said.

That first job was boring, it was embarrassing, the chicken suit looked awful.

But something happened when Giannoulas put it on.

Where he was once worried about behaving like a man, suddenly he could act like a fool.

What Ted Giannoulas could never do, the Chicken could do with abandon.

“I discovered an untapped personality in that suit,” he said. “It was like, now I have freedom. Now I’m no longer Ted.”

When the gig ended, he convinced the radio station owners to allow him to remain in the suit long enough to attend 1974 opening day for the Padres.

“I just wanted a free ticket, and I figured that was a way to get it,” Giannoulas said.

People tend to stare at a chicken in a seat. Giannoulas liked those stares. He started performing gags in the stands.

He became so popular that, several months later, Padre officials invited him to the field during the game to shoot a commercial.

He lifted his leg on an umpire, and a star was born.

When he won a lawsuit that freed him from the radio station and allowed him to wear the chicken suit anywhere, that star became national.

He has since performed at the White House, worked with Elvis Presley, written top-selling memoirs, appeared on every sort of national stage and screen.

But the one performance he will never forget is the only one witnessed by his father.

John Giannoulas never really accepted his son’s job. He scoffed at the suit.

“Don’t worry about my boy,” he would tell friends. “Even the president of the United States used to wash dishes.”

But in 1979, while fighting lung cancer that would take his life less than two months later, he finally agreed to watch Ted’s act.

“I remember him wearing a beret, and pulling an oxygen tank,” Ted said.

He paused, and it was clear that wasn’t all he remembered.

“My father laughed,” said Ted softly, his eyes wide, as if he had just heard that roar.

*

The Chicken is fuming.

He shows up in a Chicago White Sox clubhouse to say hello to old friend Frank Thomas, and the player starts shouting.

“Don’t come near me,” Thomas says. “Don’t look at me, don’t talk to me, I want nothing to do with you.”

The Chicken shows up in a Boston Red Sox clubhouse, and several players are suddenly too injured to help.

The Chicken shows up in Philadelphia, and catcher Bo Diaz agrees to be part of a gag, but only for money.

The Chicken arrives in Baltimore, and Eddie Murray refuses to give him a warmup ball for a trick.

“If only these players knew how much the fans needed to see them having fun,” Giannoulas says later. “If only they had a clue.”

*

Amy Schneider, a young marketing assistant with the Cincinnati Reds, was asked about the Chicken.

“I’ve never heard of the Chicken,” she said. “There’s a level of seriousness at a major league park now that doesn’t lend itself to outside entertainment. The players and umpires don’t want to be distracted.”

Charlie Seraphin, marketing vice president of the Kansas City Royals, was asked about the Chicken.

“It’s all economics,” he said. “The gap between the size of a Chicken crowd and a regular crowd has declined.”

Dave Oldham, president of the Class-A San Bernardino Stampede, was asked about the Chicken.

He answered in a different language.

“I want to raise my son to be a Chicken,” Oldham said. “He’s a living legend, the best, he can still fill a minor league park, still make a five-figure difference that night.”

On this night in Salem, the game had long since ended, but the entertainment continues.

The line for autographs is filled with fidgety kids and laughing adults. After two hours, a guy named Ray Woods shows up in front of the Chicken with nothing in his hands.

“I don’t need an autograph, I don’t need anything,” he says. “It was my kid’s first game and I just wanted to say thank you.”

The Chicken shakes his head. Sometimes there is nothing even he can say.

The clock ticks past midnight when two teenage girls appear out of the darkness for one final photo.

The seventh inning was hours ago. The players have long since departed. The balls and bats and gloves are locked up.

Yet as the girls approach the Chicken they are singing, softly, soulfully, their words softening the night like an old friend.

“Take me out to the ballgame, take me out to the crowd ... “

It is not a roar. It will have to do.

*

Bill Plaschke can be reached at bill.plaschke@latimes.com.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.