Post-auction, an uproar in the Craftsman clan

- Share via

It was the auction the Craftsman community couldn’t stop talking about.

In December, Sotheby’s auction house put up a rare collection of furnishings and accessories from historic homes designed by the brothers Charles and Henry Greene, the architects who created the venerable Gamble House in Pasadena, as well as other celebrated examples of the early 20th century Craftsman style in Southern California.

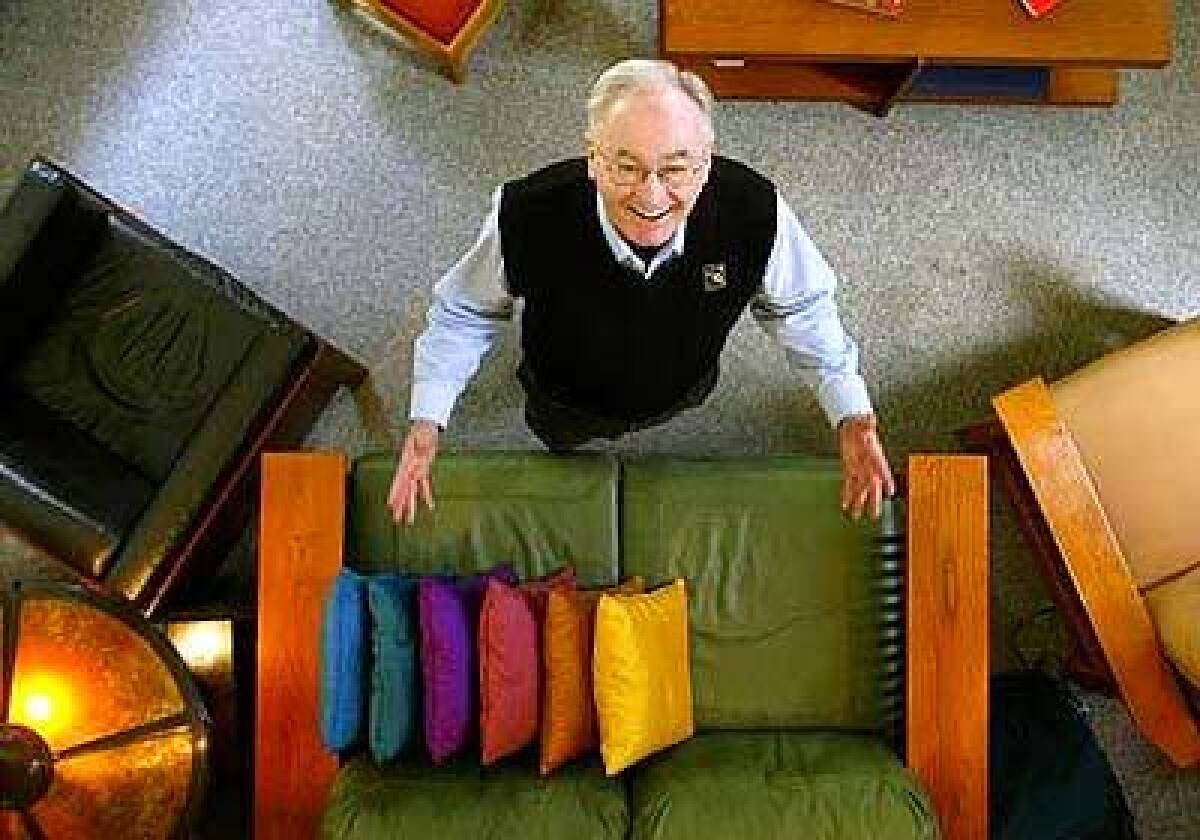

The collection was offered by an anonymous donor whose identity did not seem of particular importance until it became clear it was Randell Makinson, the former curator and director of the Gamble House. The auction, which appraisers say was the largest of its kind, netted almost $3 million.

As a result, Makinson, who helped open the Gamble House in Pasadena and ran it from 1966 to 1992, now watches his legacy hotly debated by devoted Craftsman enthusiasts.

Some scholars, dealers, preservationists and collectors say Makinson crossed an important line in the museum world by collecting and trading the very art and artifacts he worked with as curator and director of a historic home. Other prominent members laud his longtime efforts to save important Craftsman artifacts and raise the profile of the genre’s architecture and design.

The passions evident in interviews with Craftsman enthusiasts led to angry expressions such as the postcard Makinson received a few weeks ago. On the back of the postcard of a lantern from the back porch of the Gamble House an anonymous writer scrawled, “Randell, did you sell this, too?”

Makinson calls such insinuations “scurrilous” and says he does not believe he did anything wrong in selling items he had acquired while he worked in Greene & Greene scholarship, preservation and exhibition over the years. He seems baffled by the criticism.

“Lots of it had been in basements for 25 years with two inches of dirt on it. I saved it from going to the dump,” Makinson said during an interview at his condominium near Arroyo Seco, overlooking the Rose Bowl. There are several Greene & Greene homes on the street, and inside, Craftsman décor.

“I wound up with a few, mostly early pieces — I don’t call it a collection. An excited owner, or a member of the Greene family, would on occasion want me to have a piece because they were appreciative of what I’d done for the history of their father or uncle.”

Some of Makinson’s objects up for auction had been displayed at the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens as part of its permanent “Greene and Greene and the American Arts and Crafts Movement” exhibition, which is composed of items from the collections of the Huntington, the Gamble House and private donors. (The Gamble House does not exhibit items it owns from other homes on its premises.)

Appraisers noted the size of the collection and range of items. Among the most expensive pieces were sconces, desks and windows from the Greenes’ Reeve and Tichenor houses in Long Beach and the Whitworth House in Altadena. But there were less-important pieces as well.

The auction of the trove stung some members of the Craftsman community who still lament the fate of Greene & Greene fixtures taken from the stately Blacker House when it was sold in 1985. After the plunder of the Blacker House, Pasadena passed an ordinance protecting significant Arts and Crafts objects from being taken out of the house they were designed for. In Craftsman lore, the total environment is central.

The polished-teak, turn-of-the-century Craftsman style embodied by the 1908 Gamble House is a key element of Pasadena’s self-image. Claire Bogaard, former executive director of the preservation group Pasadena Heritage and wife of the mayor of Pasadena (which administers the house along with the USC School of Architecture), calls the auction “a real disappointment.”

“It worries me that a number of those pieces may have been given for safekeeping, and that the women who donated them may have believed they would remain at the Gamble House,” she says.

Makinson has been a poor steward of important objects he was given, says Ted Wells, a Laguna Beach architect who represents the auction’s anonymous buyer. The two have set up a foundation to offer the pieces on long-term loan to public institutions, considered by all a happy ending.

“You have a responsibility to those objects the same way you would with your children: You don’t just sell them to the highest bidder, you put them in the hands of the best steward,” Wells says.

Ian Berke is a San Francisco-based Arts and Crafts collector. “What a scandal,” he says. “That the director of an institution was collecting the same kinds of materials as the institution collects. You’re putting your interests ahead of that of the institution. Where the hell was the board of directors or the trustees? I would have filed a lawsuit immediately and tried to get the sale stopped.”

Makinson says he always intended to donate the items, but that health problems intervened. Makinson was recently in the hospital with pancreatitis. The high cost of medical care caused him to sell the work, he says.

In an interview at his home, Makinson said, “You always want to be a donor or the hero. But I’m not going to put the costs of my health on these kids,” pointing at the photos of grand-nieces and nephews on the wall behind him. “I was so focused on Gamble House I did not attend to my own business at home, like getting structured for retirement.”

An expert opinion

Makinson is considered a leading authority on Craftsman design and the best-known scholar of Charles and Henry Greene. His books are prominently displayed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s “Arts and Crafts” show. He’s credited by many with persuading the Gamble family to open their home to the public, and in 1966 he became Gamble House’s founding curator.“Randell is a gentleman and a scholar,” says Jeffrey Herr, a Craftsman curator and Gamble House associate docent. “Without Randell, the Gamble House might not exist. Before Randell Makinson, there wasn’t Greene & Greene as far as public consciousness.”

Makinson can still describe the day he, then a USC undergraduate, first knocked on the door of Gamble House in 1954. It resulted in a tour, lasting more than three hours, that showed him the wonders of the Greenes’ design style.

“I was fascinated with the way the Greenes put things together,” he says. “I didn’t set out to make my name: I got fascinated with these architect brothers and just did each day what seemed to be the right thing for that house.

“For decades no one gave a darn about bungalows, Greene & Greene, older houses,” he says. Before he helped Gamble House become a historic house, he points out, a potential buyer wanted to paint the Gamble House’s teak and mahogany walls white. Later, the block’s homeowners nearly sold out to a high-rise developer who wanted to turn it into what Makinson called “Westmoreland Place along the Miami shores.”

The house is now a nonprofit historic house — not technically a museum — operated under the auspices of the University of Southern California and the city of Pasadena.

Says Makinson: “There were times when the budget was very little, and I would spend my own money to keep something from being thrown out. I would buy it, because I thought there was something I needed to learn from it. So after a thousand years, I had a number of these things around me.

“Any value they might have had,” he says of the works he sold for $2.8 million, “is value I have helped develop over the last half century.”

At every possibility, he says, he shepherded gifts to the Gamble House or Huntington.

“Maybe we should consider how much Greene and Greene material he SAVED over the years through his scholarship and concern,” David Rago, publisher of the magazine Style 1900, said in a recent editorial.

Margery Hill knew Makinson when she owned the Blacker House in Pasadena. The two eventually fell out when Makinson urged Hill to grant an easement on Blacker House that would require the owner to keep the house and its fixtures intact. Hill refused.

When Blacker House itself was sold in 1985 some suspected Makinson — who publicly denounced the sale in ringing tones — as having a hand in its sale to Barton English. Years later, English told the New York Times that he purchased the house because “Randy Makinson mentioned at a party in Pasadena that the house was for sale and that anyone who bought it could make a killing on it.” Makinson called this “garbage” motivated by English’s “attempt to discredit me.”

Hill, who sold the house not suspecting it would be stripped, spoke of her sense of betrayal from Northern California.

To Hill and other critics, Makinson is a charismatic figure who used his position and reputation.

“He imposed himself on me from the very moment I took hold of the house. When I first moved there, when I was having some drapes made, one of the sconces was in the way, so he talked me out of it. And I don’t remember the details, but he talked me out of the large fountain outside that Henry [Greene] made,” Hill said.

Makinson says the fountain was going to be bulldozed; he has “no recollection” of the sconce. Venice art dealer Bryce Bannatyne says Makinson’s late business partner — an antiques dealer — offered the sconce to him for sale in the late ‘80s, but he declined.

“It was very easy to like Randell at the beginning,” says Hill. “He was a good-looking young man, very personable — very, very convincing. He knew these owners were so proud of their houses that of course they would be willing to donate the work to Gamble House. We were all vulnerable, and he put on this false charm.”

Admirers of Makinson see things differently.

“I learned so much from Randell,” says Jacque Heebner, whose late husband hired him as restoration architect of the Greenes’ Reeve House in Long Beach. “He makes the property come to life; he orchestrates the home. Randell had a love affair with this architecture.”

When Makinson worked for the Heebners in the 1980s, “he said, ‘Were the Greenes alive today, they would allow you to bring your personality into the house,’ ” Heebner recalls. Her husband gave Makinson two light sconces and a large window that he “probably would have thrown out.” The sconces sold at the Sotheby’s auction for more than $100,000. The window is valued at $350,000. In Pasadena, after the stripping of Blacker House, such an exchange would have been illegal: An ordinance was passed to keep furniture and fixtures designed for a home from leaving it; Heebner has no second thoughts about removing the sconces, and says Makinson “preserved and protected” those pieces, she said.Under scrutiny

The criticism of Makinson for assembling a personal collection while he served as curator and director of the Greene & Greene masterpiece is echoed by experts in the workings of the museum world. Although the Gamble House is not a museum, these experts say such actions can be a misuse of that kind of position.“You’re not supposed to use your position for personal gain,” says Jason Hall, spokesman for the American Assn. of Museums. Because nonprofits are given tax breaks, he says, they and their employees are under scrutiny. “To do otherwise could potentially imperil their nonprofit status.”

But this scrutiny is not unique to museums, says Stephen Weil, a scholar emeritus at the Smithsonian Institution’s Center for Museum Studies. “The rule is not different from the corporate opportunity rule in the business world. Someone who is an insider at a corporation should not grab the opportunity, or divert the opportunity, for himself. It’s a legal breach.

“Your first duty is to the institution, and if something becomes available for the institution, you should step aside,” Weil says.

Makinson finds the talk about museum ethics irrelevant.

“Mr. Gamble made it very clear,” he says, “that this was not to be a museum. I always said it was a house with a slightly larger family.” James Gamble, he says, did not want Greene & Greene items from other homes displayed in Gamble House.

Makinson says that “a few” of his gifts came while he was running the Gamble House. “They may have been an outright gift. I would say, ‘Is this for me, or them?’ ”

The current director, Edward Bosley, says that the house differs from a museum only in a few details. “The Gamble House does adhere to museum professionals’ code of ethics which says that you don’t collect within your area of interest.”

“It’s very dicey to take gifts while working as a director at a not-for-profit,” says the Smithsonian’s Weil. Personal gifts should be rigorously documented to avoid confusion, he says.

“If someone could have known the value of the work, its aesthetic value, its intrinsic value, it was Randell,” says Sue Mossman, executive director of Pasadena Heritage. “When you wear the hat of a director, there’s a level of trust that goes with that. The bar [for ethical behavior] is set higher.”

An edgy style

USC, which jointly oversees the house, follows a university-wide ethics code that forbids conflicts of interest that “compromise the integrity of the individuals involved” and protects “resources belonging to others which are entrusted to our care.”Robert Harris, former USC architecture dean, says Makinson has long attracted rumors and gossip because “he always seems to be doing something interesting and on the edge.” Although the jacket copy on Makinson’s latest book identifies him as a professor emeritus at the school of architecture, the university says he’s never been one. Makinson says he taught classes at USC before joining the Gamble House, but never became a professor there.

He always intended to give the work to Gamble House, Makinson says. “I wish I was in the position to be another local hero. But I don’t see a lot of these [critics] giving work away, themselves.”

“A lot of them are old friends,” he says of his accusers, who he thinks have overreacted. “I’ve overreacted myself to things over the years. I think the people who weren’t contacted by me that [the auction] was going to take place were a little hurt.”

Preservationist Bogaard feels split when assessing Makinson’s legacy. “Here is a man who dedicated his career to educating the public about Charles and Henry Greene,” she says of the books and labors that put the brothers on the architectural map. “Now, by selling Greene & Greene artifacts, many of which are believed to have been given to him for safekeeping, he has turned his back on that fine career and may go down in history as a villain.”

In the interview at his home, Makinson at one point sprints up a flight of stairs to read words engraved above his landing. It’s a quote he attributes to Elbert Hubbard, a pithy, self-promoting Arts and Crafts designer: “To escape criticism,” he shouts, barely suppressing a laugh, “do nothing, say nothing, and be nothing!”

It’s clear what he’s getting at.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.