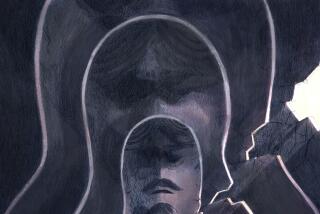

‘Creation’

- Share via

The difficulty of taking on the biography of a man of science is so often the science itself, which entails hours of observation, painstaking notes, endless experimentation and much deep thinking. Still, in Charles Darwin’s case, considering his “On the Origin of Species” would forever change how we view and debate our very existence, you’d hope for a little high drama from filmmaker Jon Amiel’s “Creation.”

Instead there is angst, lots of it, for Paul Bettany to muck around in as he portrays the great evolutionist. Not that angst is a bad thing, but here it makes a muddle of Darwin’s story. Even the sheer beauty of the setting, the sets and the attention to the detail in re-creating his family life in a bucolic English village in the 1850s is not enough of a distraction, though it is a reminder of Amiel’s long history with period pieces, “Sommersby” probably the best known here.

For most of us, the image of Darwin is of an ancient man, serious of mien, great hoary beard. In “Creation,” we catch him midlife in the throes of researching and writing his seminal text, looking in old photos remarkably like Bettany does today.

Initially Charles and his family -- Bettany’s significant other, Jennifer Connelly, portrays Darwin’s wife, Emma -- seem to live an enchanted life, with dad turning his scientific observations of other cultures and species into grand stories for the children, of which there will eventually be 10, though only seven survive into adulthood.

For the Darwin brood, a trip to the shore turns into a home-schooling adventure on how the strata of rocks are created; a walk in the forest with the sight of a fox catching a rabbit is cause for a survival-of-the-fittest lesson.

But when dad starts talking about explorations of more primitive places and peoples, suddenly the action shifts to jungles and distant shores, which might be OK if that were the only time-traveling we would be doing. It is not because of daughter Annie.

The precocious and much-loved Annie Darwin (a very promising young Martha West) died at 10 after going through treatment for a fever that frankly seems reminiscent of water-boarding, but then it was the 1800s. Charles, who already had bouts of an undiagnosed illness that looks a lot like depression, was sent into a very deep tailspin by Annie’s death.

Before long, Charles and an afterlife Annie are having lots of philosophical conversations as he worries that his thesis will kill the notion of God and other thorny issues, particularly since wife Emma is especially devout.

Soon you realize that Annie’s death has sent the director into a tailspin of his own. With his allegiance divided between father and daughter, it becomes increasingly difficult to know whom the film really belongs to.

You can almost see screenwriter John Collee’s struggle to adapt the book “Annie’s Box” by one of Darwin’s descendants, Randal Keynes. Try as he might to work three narrative threads -- Charles’ present day, which is as concerned with his personal demons as his science; his past; and his ongoing conversations with an afterlife Annie -- into a coherent piece, “Creation” never really gels.

That leaves the actors struggling to make the best of it. Though you might expect the scenes between Bettany and Connelly to have some added warmth, there is a hardness to Emma that makes their distances and disagreements actually work better. Both are best with the children, and Bettany’s scenes with West are the most sensitively drawn of the film.

The prospect that this role would officially shift Bettany to a bigger stage, taking him from the character roles that have become his specialty to leading man status, dies a sort of Darwinian death from bad plotting. Bettany spends so much of “Creation” in one fevered flop sweat or another it’s a wonder that “Origin” was ever finished.

As to the science, Amiel makes some attempts at a visual shorthand here and there to take us through some of Darwin’s theoretical progression: a school of fish turning into a swarm that echoes the same shape as a flock of birds in flight, the fallen baby bird becoming food for grubs. But in the end, they just become more loose pieces of a puzzle that never evolves into a film.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.