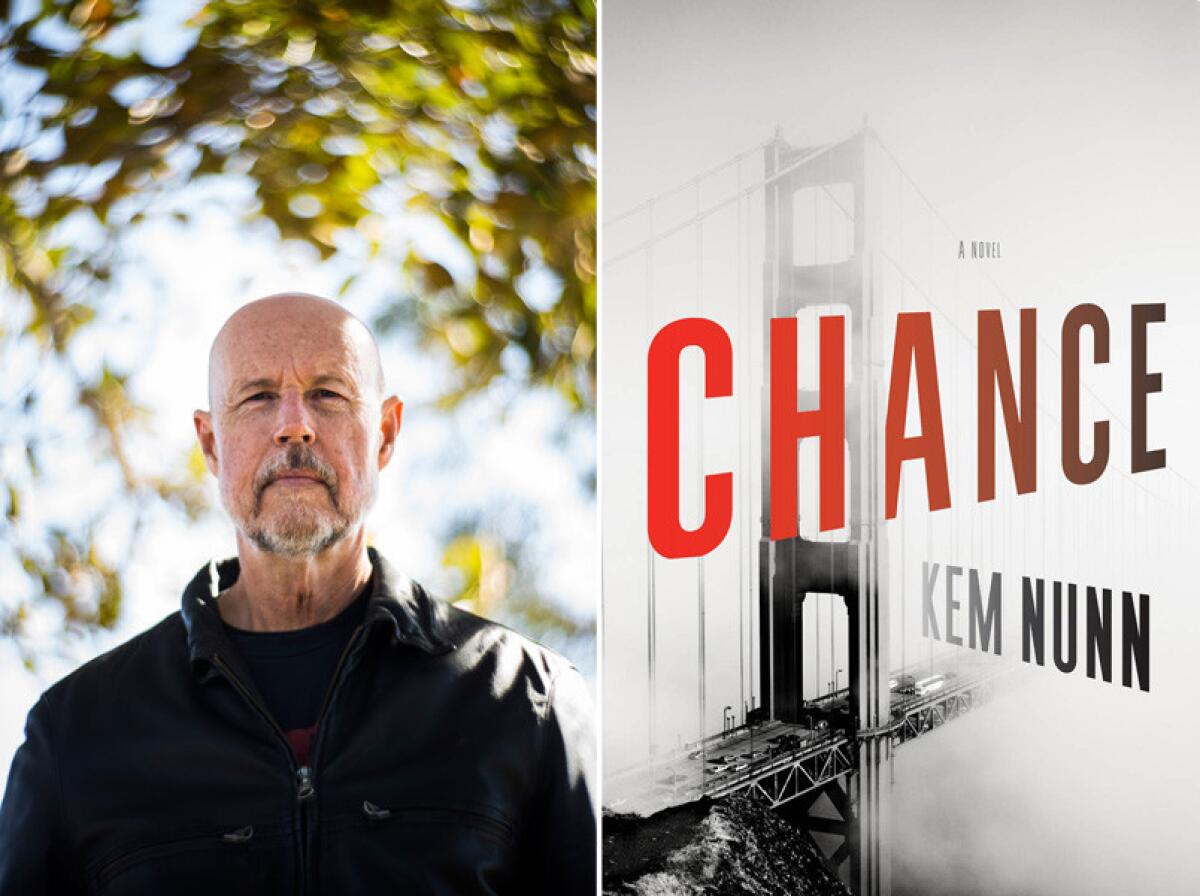

Kem Nunn’s ‘Chance’ gets under California’s skin

- Share via

Is it too much to compare Kem Nunn to Raymond Chandler? Both have used the loose frame of genre to write enduringly and resonantly about the dark side of the California dream. For Nunn, this has meant an exploration of boundaries, both actual and metaphorical; his last novel, “Tijuana Straits” (which won a 2005 Los Angeles Times Book Prize), traces the shifting landscape of the physical borderland.

At the same time, there is also a willingness to take risks, to play against expectation, which marks both Nunn’s fiction and his TV work on “John from Cincinnati” and now “Sons of Anarchy.” His writing has been characterized as “surf noir,” but really, that’s just a convenient placeholder, going back 30 years to “Tapping the Source,” in which a teenage boy’s search for his sister leads him to the unexpected fringes of a Southern California beach community.

Like Chandler, Nunn’s great subject is what lies beneath the surface, the desolation that infuses us at every turn. As Eldon Chance, the central character of his sixth novel, “Chance,” reflects, “What difference would any of it make when all was said and done? When entropy and darkness had had their way?”

“Chance” is very much a book about entropy and darkness. It also takes its share of risks, beginning with the name of Nunn’s eponymous protagonist, a forensic neuropsychiatrist in San Francisco who “made the better part of his living explaining often complicated neurological conditions to juries and or attorneys.” Such a formulation can seem contrived, especially in a novel like this one, which is, at heart, about uncertainty.

That, of course, is another risk, to build a narrative in which neither character nor reader ever fully knows what’s real and what’s perceived. For Chance, this is true of his personal as well as his professional life: a collapsing marriage, a rebellious teenage daughter, trouble with the IRS.

And yet the thrill of “Chance,” the vividness of it, is that Nunn somehow makes this work — not cohere, exactly, because the novel is fundamentally an exploration of incoherence but reflect the awful incomprehensibility of the world. For Chance, 49, astray “within a dark woods where the straight way was lost” (to steal a phrase from Dante), this is both a practical and a philosophical consideration; he is self-aware enough to see himself slipping off the straight and narrow, and yet powerless to stop himself.

“He could see all of this for what it was,” Nunn writes of his main character, “the half-mad quixotic gesture better dreamt than executed because well … because that was what life was like in the end. It was an image in a glass darkly. It was all just half lived.” Just how half-mad becomes apparent when he grows infatuated with a patient, the elusive Jaclyn Blackstone, wife of a corrupt and brutal Oakland cop who quickly becomes the novel’s counterbalance, the yang to Chance’s yin.

This, of course, is another kind of border: a blurred one, in which darkness bleeds in and out of light. It’s a tension that Chance, like all of us, must wrestle with, between propriety and something far more fierce and wild.

Early in the book, Chance meets a former Army ranger known only as D, a mountain of a man who restores furniture for an antique dealer on Market Street. D is damaged also: diabetic, sleep-averse, defined by a tangle of violence below the skin.

“People talk about self-defense,” he says. “I’m defending, I’m losing. I want the other guy defending while I attack.” He proves the point one night in the Tenderloin by taking on four muggers as Chance watches, beating them so badly it is uncertain they’ll survive.

For D, this is a way of showing Chance how to deal with Jaclyn’s husband, who may or may not be making threats. “Doesn’t make any difference how many people I’m fighting,” D continues, “I want them all defending because that means I’m dictating the action. I’m the feeder. As long as I’m the feeder, I win. … Right now, this cop is the feeder. You’re the receiver. You need to turn that around.”

The problem is that even Chance can’t tell how much he is being fed and how much he is feeding himself. This becomes increasingly treacherous the more his daughter gets into trouble, first with pot and then by disappearing with a boyfriend who may or may not be mixed up in Jaclyn’s world.

“He’d read somewhere,” Nunn writes, “that the family was an instrument of grief and there were times when it seemed to be so.” But equally important is the understanding that he is compromised, blinded even, by what he loves. “Ever heard of The Frozen Lake?” D asks. “It’s the thing you want so badly you’ll go to the center of a frozen lake to reach it.”

When it comes to Chance, that means his daughter but also his obsessive tendency to want what he can’t have. Until now, he’s been able to keep that at arm’s length, but this hunger for Jaclyn cracks open the veneer of his straight life to reveal the turmoil within.

“There’s a whole bunch of people out there who think the world is an orderly place,” D tells Chance, “that if things get weird they can run to the cops, hire an attorney. … They’re the ones who think it’s a game. They even think there are rules. Go to the cops with what you’ve got right now and see where it gets you. Rules favor the people who make them.”

What this suggests is that D too is an agent of chaos, like nearly every character here. Chance knows it but can’t do anything about it, especially after he embraces the other man as not just an enforcer but a kind of spiritual guide.

“You never know what you’re capable of until you find out what you’re capable of,” D likes to say — a bit of sophistry, to be sure, but also the message of the book. For Chance, every step away from the expected is a step toward a perverse freedom in which he, and not Jaclyn’s husband, is calling the shots.

“The essential feature of a shared psychotic disorder (folie à deux),” Nunn writes, “is a delusion that develops in an otherwise healthy individual who is involved in a close relationship with another person (sometimes termed the ‘inducer’ or ‘the primary case’) who already has a psychological disorder with prominent delusions.” The feeder and the receiver again.

The power of this disturbing and provocative novel is that it leaves us unmoored among the signposts of a morally ambiguous universe in which, even after we have finished reading, it is uncertain who has been feeding whom.

Chance

A Novel

Kem Nunn

Scribner: 322 pp., $26

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.