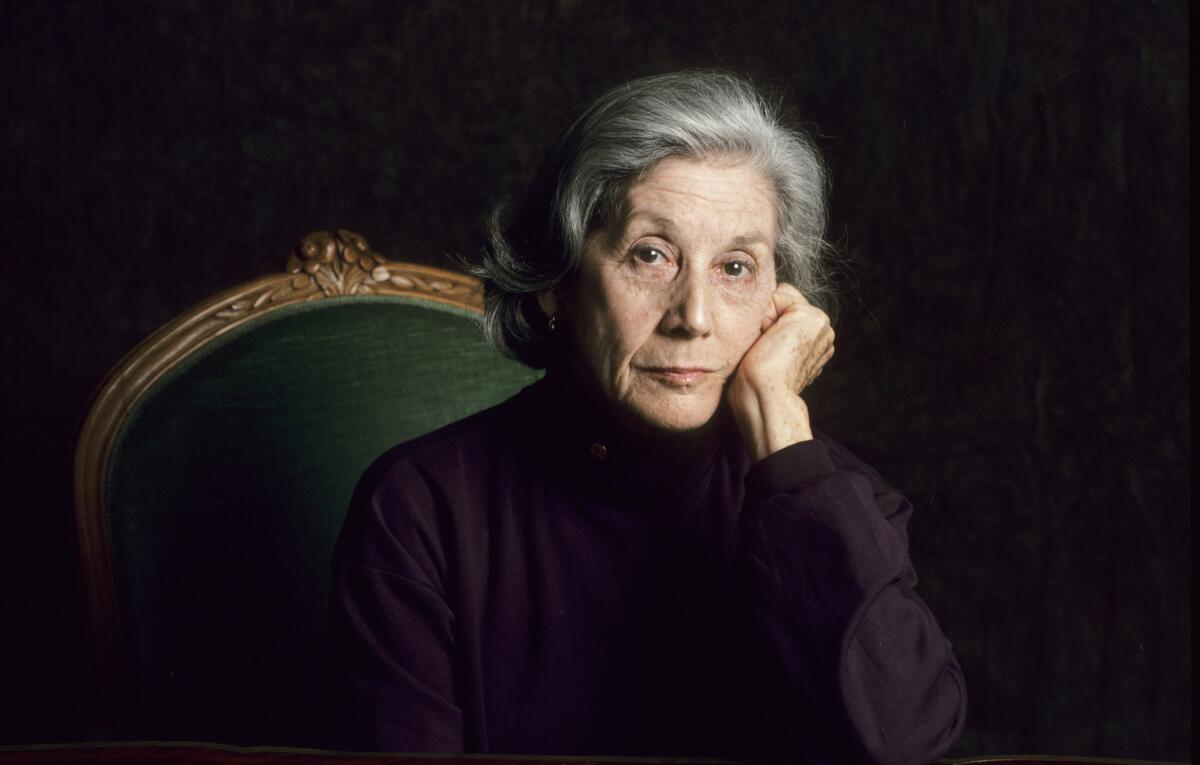

Nadine Gordimer offered a model of how to use books as social force

- Share via

Nadine Gordimer, who died Sunday at age 90, understood the power of writing as a moral force. Not only in terms of literature (although that too) but also politically, in a country -- apartheid-era South Africa -- where such commitment carried a high price.

We think of Gordimer as an international figure, winner of the 1991 Nobel Prize for literature, author of more than 40 books, including “A Sport of Nature” and “July’s People” as well as the 1974 Booker Prize-winning novel “The Conservationist,” but she is perhaps most notable for what she did not do: fold under the pressures of the Afrikaner regime that came to power in 1948, institutionalizing racial inequality as a matter of law.

“I am not by nature a political creature,” she told the Paris Review in 1983, “and even now there is so much I don’t like in politics, and in political people -- though I admire tremendously people who are politically active -- there’s so much lying to oneself, self-deception, there has to be -- you don’t make a good political fighter unless you can pretend the warts aren’t there.”

At the same time, her body of work -- short stories, novels, essays, spanning more than 60 years; her first book, the story collection “Face to Face,” appeared in 1949 -- offers a model of how to function as a writer of engagement, to use art, literature, as a social force.

“We get from newspapers the so-called facts, we get the dramatic events,” she said in Bookforum in 2006, after the publication of her 14th novel, “Get a Life.” “But novelists, poets, and playwrights show how people lived before, what brought them to this dramatic event, and how they are going to deal with their lives after it.… I always go back to the wonderful example of Tolstoy’s ‘War and Peace’: If you want to know what really happened to people in the Napoleonic Wars and Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow, you can read the facts in the history books. But to know how it was to live then, we have to read ‘War and Peace.’ ”

This is not a notion with which we are particularly comfortable in the United States; we prefer to marginalize our art as entertainment or at least as distinct from social realities. As Gordimer understood, however, the very act of making art is political, although (here’s the tricky part) the politics is not what makes it art.

Her fiction was not didactic but rather nuanced, driven by character and situation, portraying realistic people engaged in the tumult of their lives. Even her 1979 novel “Burger’s Daughter” -- regarded as the most overtly political of her books, and one of three to have been banned for a time in South Africa -- turns, in some fundamental fashion, on the story of a woman, daughter of a white anti-apartheid activist modeled on Nelson Mandela’s defense attorney Bram Fischer, who is trying to find her place in a society that is radicalizing so quickly that it’s impossible to keep up.

“[Y]ou could say on the face of it,” Gordimer once observed about the novel, “that it’s a book about white communists in South Africa. But to me, it’s … a book about commitment. Commitment is not merely a political thing. It’s part of the whole ontological problem in life. It’s part of my feeling that what a writer does is to try to make sense of life. I think that’s what writing is, I think that’s what painting is. It’s seeking that thread of order and logic in the disorder, and the incredible waste and marvelous profligate character of life.”

What Gordimer was getting at is the faith that politics is part of existence, that the societies we create tell us a great deal about who we are. Not only that, but that it is in how we respond to the situations in which we find ourselves that our identities and legacies are forged.

Gordimer responded to a lot over her 90 years; a member of the African National Congress, she was active in the movement from the early 1960s, and she helped edit the “I Am Prepared to Die” speech Mandela gave from the defendant’s dock during his trial in 1964.

Although she was never jailed or prosecuted -- in part, perhaps, because of her international acclaim as a writer -- she used her position to push for social justice, refusing honorary degrees from South African universities and becoming an anti-censorship advocate. As recently as last month, she chided South African President Jacob Zuma for proposing legislation to limit the publication of “sensitive” material; “The reintroduction of censorship,” she declared, “is unthinkable when you think how people suffered to get rid of censorship in all its forms.”

Amen to that … but then this, of course, was central to Gordimer, both as a writer and as a person, the ability -- no, the requirement -- to report back from the trenches, to tell stories that grew out of the world in which she lived.

“My writings,” she said, “arise out of the tensions over many years between my personal development as a human being in relation to the world, to the people around me, to my relationships and the pressures from outside my consciousness -- the way our lives are ruled by the laws, the social mores which impinge upon us. And out of that tension is the ability to imagine other people living like this, to go outside one’s own experience. And out of the observation and the instinct to identify -- I imagine it is this way with others -- come novels and stories.”

Twitter: @davidulin

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.