‘Round About the Earth’ traces a history of ambition and colorful personalities

- Share via

Round About the Earth

Circumnavigation From Magellan to Orbit

Joyce E. Chaplin

Simon & Schuster: 560 pp., $35

A trip on a 140-foot sailboat helped inspire Harvard professor Joyce E. Chaplin to write “Round About the Earth: Circumnavigation From Magellan to Orbit” — and that may explain the enthusiasm she brings to the many-stranded narrative. At the very least, it underlies her sympathy for sailors on small boats heading into rough, unknown seas.

This history, the first of its kind, is a lively charge through 500 years of worldwide exploration (and beyond). Chaplin sets to the task by carving that time span into three parts.

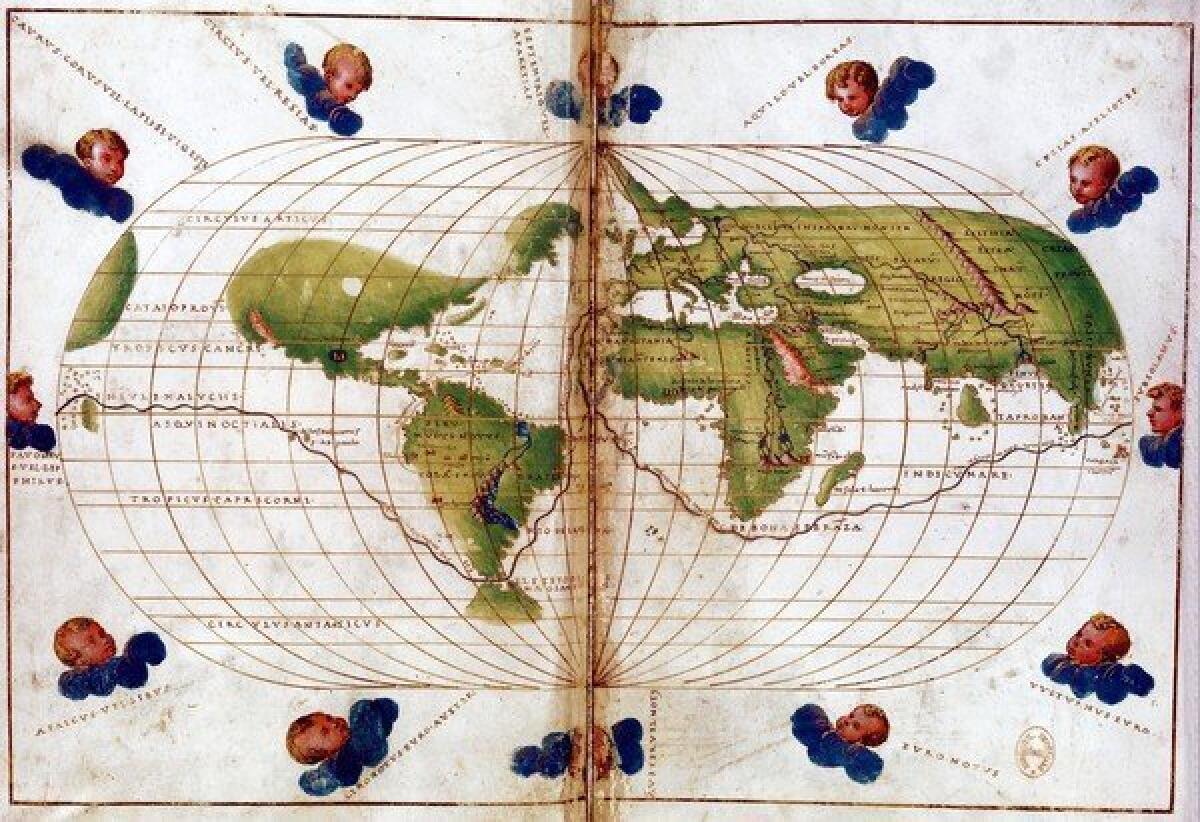

Magellan launches the tale. History remembers him as the first to make it around the globe, but it was actually his boat and crew that completed the circuit — Magellan was killed in the Philippines in 1521. For the next 250 years, humans made their tenuous way around the globe. Apart from dangerous weather, rotting ships, and threats from fellow men, they had to contend with the disease and physical hardship of extended trips at sea. More than half who sailed never came back. As Chaplin elegantly puts it: “The planet simply shrugged them off.”

Chaplin’s second period, the “age of confidence,” begins in the late 18th century, after British scientists and Capt. James Cook figured out (mostly) how to prevent scurvy. Soon steamships overtook sailing ships, rail lines started to gird the earth, and the people who attempted to go all the way around diversified: not just soldiers and sailors but adventurous individuals — even women. Think “Around the World in Eighty Days” — everyone else did, using Jules Verne’s iconic novel as a guide, jumping off point and challenge.

The third period begins with 20th century flight and soars outside our atmosphere, but rather than a triumphant coda, Chaplin sees a new doubt emerging. Now that we are literally able to see our entire planet from orbit, we can perceive its fragility. Once we were at risk of being destroyed by the planet; now it’s the other way around.

Chaplin enters this enormous subject via the first-person narratives of the travelers, from Antonio Pigafetta, who sailed with Magellan, to astronauts who have spent time in the International Space Station. Along the way are mostly forgotten adventurers, including Woodes Rogers, who liquored up his circa-1710 crew to keep them from getting mutinous ideas in the Pacific; Ida Pfeiffer, a wealthy widow whose 1846-48 tour between flourishing outposts of imperialism included ship, rail and a mule caravan, and I.S.K. Soboleff, a displaced White Russian who spent 1928-30 traveling the world with, he wrote, “no passport, no visas, a broken-down old bicycle, and twenty Mexican dollars in my pocket.”

That’s just a sampling; Chaplin brings many, many more stories into this narrative, which, like the earliest sailing ships, is packed to maximum density. Her frank touch, however, gives it a lightness. “It is no good wishing he were a nice person; he was more or less a ruthless thug,” she writes of Magellan, adding, “The first commander of a circumnavigation who resembled a nice person would not draw breath until 1723.” (That was John Byron, grandfather of the famed poet.)

For centuries, Portuguese and Spanish ships raided each other’s vessels and colonies, while wantonly capturing and enslaving native peoples. The British, late to the game, officially licensed privateers to harass their counterparts, particularly those carrying gold. Some of the accounts Chaplin uses were only partly published in their day — these adventure tales were wildly popular, but competing European powers kept their discoveries close.

Word got out, of course. Verne’s “Around the World in Eighty Days,” published in 1873, was inspired by newspaper reports he’d read. Despite being fiction, and a satire — Verne, a Frenchman, created supercilious Englishman Phileas Fogg — the book’s speed-focused globe-trotting set a real-life standard. In 1889, Nellie Bly set out to defeat the record and write about her experience for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World — it took her 72 days, 6 hours, 11 minutes.

Once speed became the focus, Chaplin reminds us that modern circumnavigation came with a different set of physical challenges. Worldwide travelers trying to beat other worldwide travelers were often exhausted. This was the case even as technology improved — contests to fly around the world were even harder on the participants than those in which they traveled on boats and trains.

By the late 19th century, when just about anyone of means could travel around the world, the story has too many threads. Chaplin jumps from one to the next to explain how the process changed and evolved, but leaves some of the interesting pieces on the cutting room floor. Wiley Post, an innovative one-eyed pilot who became the first man to fly around the world solo, gets as much attention as any, including the note that he was friends with Will Rogers — but you’ll have to go elsewhere to learn that the two died together, in a plane Post was flying. There’s too much but not enough — like the space station where astronauts observe 30 dawns and twilights in the course of a single (terrestrial) day.

The narrative slows again with space exploration, which at its start had a relatively small set of players. Here, the Russian space program is well detailed — not only is it less familiar to American readers, it often preceded us. Chaplin has a soft spot for its doomed canine pioneer. Space, orbit, the moon, Mars: As quick as it can, the book explains satellites, debris fields, and the quandary of whether humans can survive without gravity (reminiscent of the challenge of scurvy). Nevertheless, the story can’t keep up; NASA promises news “for the history books” from Mars is coming in December.

Chaplin’s greatest feat is convincingly demonstrating that circumnavigation is not just a series of dates, death tallies and speed records. “Over the last 500 years, the physical globe has been as central to our collective history as it was to each individual around the world traveler,” she writes. In the present day, that sense of collective, global history is more urgent than ever.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.