‘The Burgess Boys’ lack compelling main characters

- Share via

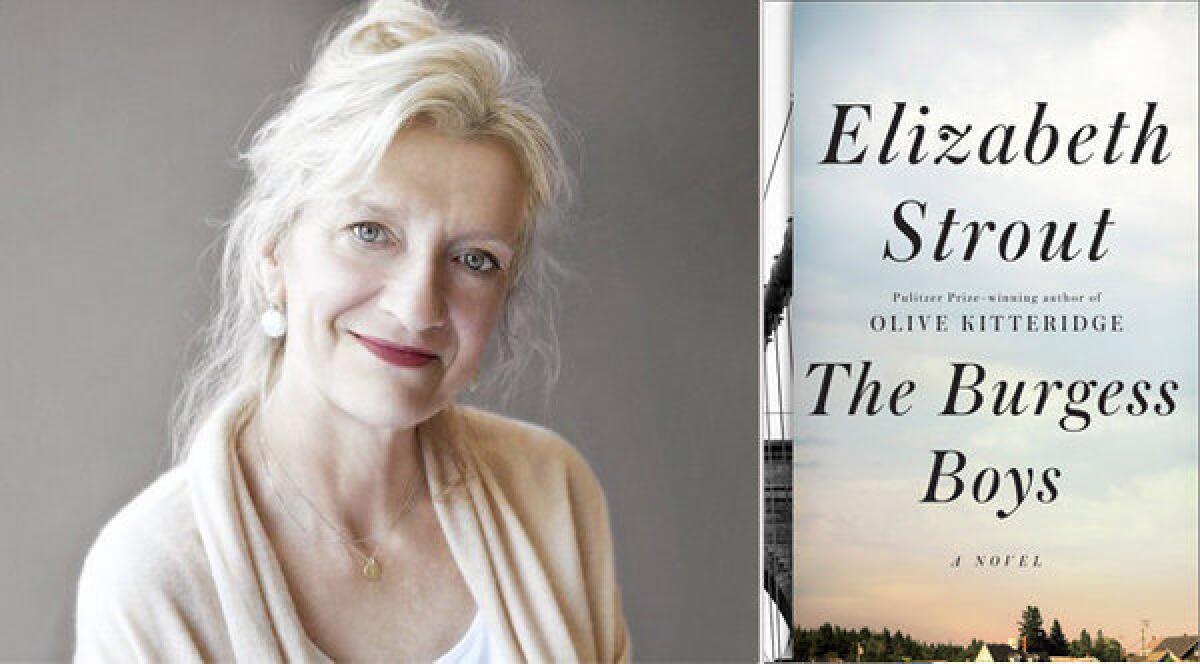

Elizabeth Strout wrote about a small Maine town in her Pulitzer Prize-winning 2008 novel “Olive Kitteridge,” a lyrical and heartbreaking series of interconnected short stories that revolve around the overbearing title character. Things happen in “Olive Kitteridge”: People are married and divorced, they die, have affairs and are held hostage at a hospital by a group looking for drugs. But it isn’t the things that happen in the book that made “Olive Kittredge” so special, it’s the way people continue to go about their lives the best they can after those things happen.

Strout writes beautifully about human endurance in the face of the struggles of day-to-day life, allowing the reader to peer into characters’ hearts and see — feel — their sadness and their joy.

“The Burgess Boys” is Strout’s first book since “Olive Kitteridge,” and she again returns to a small town in Maine. The novel tells the story of the Burgess family — twins Susan and Bob and older brother Jim, who grew up in Shirley Falls, Maine, coping with a family accident from their childhood. Guilt wracks each of them, especially Bob, over the mishap that left their father dead.

When the book opens, Bob and Jim are lawyers living in Brooklyn, while Susan remains in Maine. When her lonely and awkward son gets arrested after throwing a pig’s head into a local mosque — a reckless act that the news media dubs a hate crime — the three reunite to rehash old wars and battle a new one.

“The Burgess Boys” shares milestones with Strout’s previous book — people have affairs and get divorced and get together and miss their children — but the events feel heavier here, perhaps because they involve a trial and questions about prejudice. And the characters seem ill-equipped to deal with these events. If “Olive Kitteridge” was about human fortitude in the face of heartbreak, “The Burgess Boys” is about the main characters’ inability to cope with their lives and one another’s.

The narrative mostly follows Jim and Bob, giving Strout a chance to stick with her characters for a while rather than dropping in and out of their lives as she did in “Olive Kitteridge.” But they’re not appealing creations. Jim is a successful and arrogant lawyer with a rich wife, Bob is a divorced and affable alcoholic. Neither of them prove competent uncles or brothers, although they try, sometimes. And when both have problems in their love lives, it’s difficult to really care.

Some of the most compelling parts of “The Burgess Boys” aren’t about the Burgesses at all but about people in the town. This may be unnerving for readers focused on the title characters, but it’s a reminder of where Strout is strong. About the town’s police chief, Gerry O’Hare, she writes, “In all his years as a policeman, he had never understood — why would he understand? — how it was that some things happened to some people and not to others. Gerry’s own sons had turned out well. One was a state trooper and the other was a high school teacher, and who could say why he and his wife had had this luck? The luck could end tomorrow. He had watched people’s luck end with one phone call, one knock on the door.”

Strout also relates snippets of the story from the perspective of the Somalian refugees in town. It’s an interesting angle from which to view small-town Maine but also a fleeting one; those glimpses into other, foreign, lives are quickly overshadowed by the travails of the Burgess family.

Strout began her career as a short-story writer, and she is strongest in that capacity: her prose sings, and her knack for dropping in on characters and illuminating their lives in a few sentences is compelling. In a powerful three-page chapter, Susan, remembering her childhood in a conversation with her elderly tenant, Mrs. Drinkwater, thinks, “No one wants to believe something is too late, but it is always becoming too late, and then it is.” But in “The Burgess Boys,” as she writes of Jim and Bob, Somalians and Mainers, law firms and marriages, Strout isn’t able to pull the disparate pieces together. Somehow, in writing a novel, Strout has lost the story.

The Burgess Boys

A Novel

Elizabeth Strout

Random House: 336 pp., $26

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.