New journal ‘Radio Silence’ connects writing and rock ‘n’ roll

- Share via

In college, I once wrote a paper arguing that rock ‘n’ roll songs were poetry in sonic form. I was not, at the time, aware of Richard Goldstein’s 1972 anthology “The Poetry of Rock,” which made a similar case, gathering lyrics and presenting them as verse, but I was under the sway of a cluster of poet/musicians: Lou Reed, Patti Smith, Jim Carroll, even Jim Morrison, whose posthumous spoken word record “An American Prayer” I liked to put on from time to time.

Partly, my thesis was self-serving; I was writing and playing my own songs, and I wanted to invest them with a gravitas I wasn’t sure they had. Yet even more, I was driven by my love of the music, my absolute certainty that it was tapping into something, that in the intersection of sound and language, I might find a shadow territory, one that I could make my own.

At the heart of this, I’d later come to realize, was the tension between (let’s call it) trash and art, a line staked out by writers such as Ellen Willis and Richard Meltzer, whose magnificent “The Aesthetics of Rock” was either the first recorded application of critical theory to rock music or one of the best practical jokes ever to come out of the counterculture, depending on your point of view.

I kept thinking about this as I read the first two issues of “Radio Silence,” a Bay Area literary journal that seeks to trace the relationship between rock music and literature. The debut issue sets the template: contemporary writers such as Geoff Dyer, Sam Lipsyte, Tobias Wolff and Rick Moody interposed with some unexpected classics -- Edna St. Vincent Millay, F. Scott Fitzgerald -- whose writing echoes the spirit, if not the letter, of rock ‘n’ roll.

Both Millay and Fitzgerald, after all, were larger-than-life figures, tuned into Greenwich Village and the Jazz Age -- the countercultures of their times. It’s a stretch to read them in terms of rock, but it’s a stretch that works, and “Radio Silence” makes the confluence explicit by juxtaposing Fitzgerald’s story “Winter Dreams” (reprinted in its original form for the first time in 90 years) with an essay by his great-granddaughter Blake Hazard, who is in the band the Submarines.

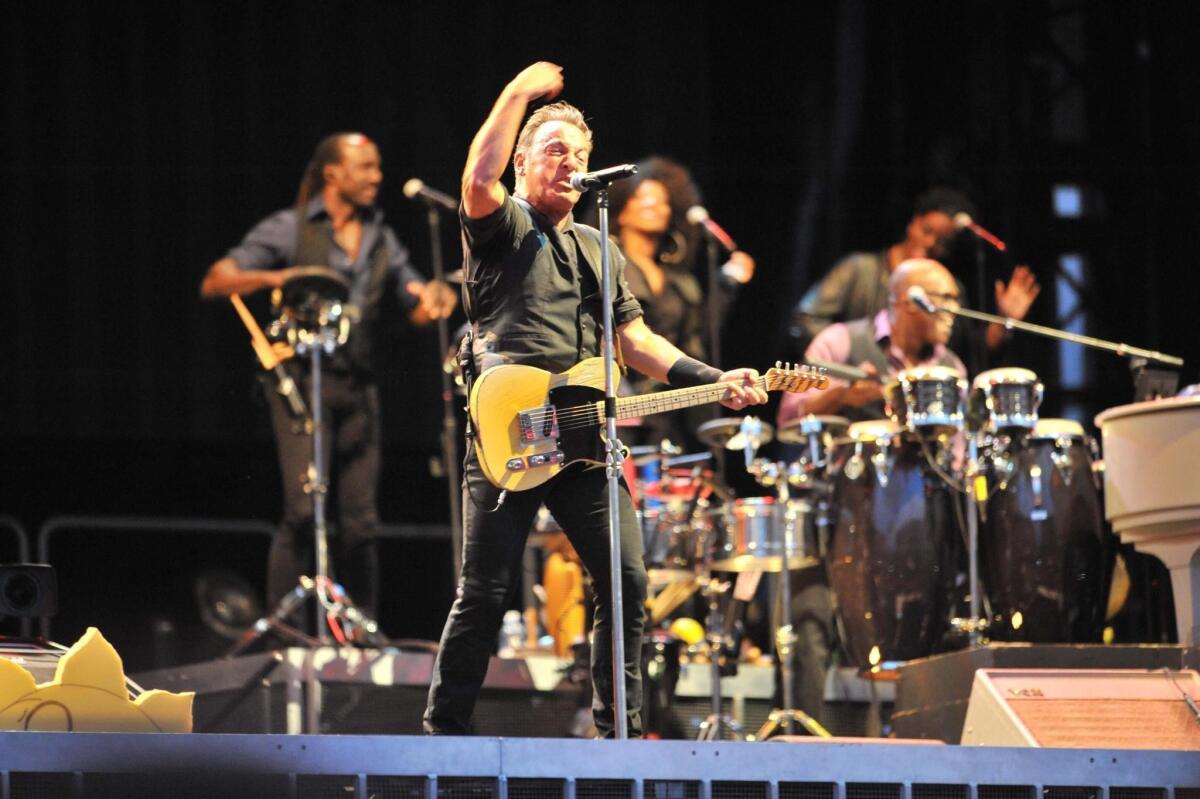

Issue Two, which has just come out, is even better. It opens with a conversation between Bruce Springsteen and former U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky, moderated by John Wesley Harding: “For me,” Pinsky said of his process, “an awful lot of it is like noodling at a piano or playing with colors or pencils, except it’s syllables. I’ve always said I write with my voice.” It’s an almost perfect invocation, tracing as it does the impulse of expression all art shares.

“I’ve been trying to deconstruct why I am drawn to particular artists when I am in crisis,” Zach Rogue wrote in “The Mourner’s Handbook,” an essay that begins with the death of the author’s father before gliding into a list of the singers (Neil Young, Otis Redding, Elliott Smith, Joni Mitchell) who “help me when things feel unbearable.”

Here, of course, we’re brought face-to-face with why we turn to books or music (or anything) -- for consolation or connection, to see something of ourselves in someone else. It’s not redemption, exactly, but respite, the recognition that for this moment anyway, we are not alone.

That’s what I was trying to get across in that long ago college paper, the way these songs, they moved me, as much and as importantly as anything I’d ever read. And it’s a sensibility “Radio Silence” shares.

Or, as John Steinbeck once commented to Woody Guthrie: “How could you say in twelve verses what it took me an entire novel to write?”

ALSO:

Matthew Sharpe’s storytelling experiment

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.