How Obamacare brought health coverage to the people, in four amazing charts

- Share via

There are many elements to the conservative mantra that the Affordable Care Act is a “disaster” -- it’s too expensive, it doesn’t cover all that many people, it’s driven up costs for everyone, etc., etc. None of this is news to anyone who follows healthcare affairs. Nor is the fact that these criticisms all are either false or misleading.

A new study from the Society of Actuaries graphically shows how false and misleading. It documents the sharp rise in coverage and medical utilization in the individual health insurance market starting in 2014, when the ACA’s insurance exchanges began operating. The actuaries also document that costs and utilization trends in the large- and small-group market -- health insurance provided by employers -- remained stable, fell, or continued trends that already existed before the advent of the exchanges.

The report, a collaboration with the Health Care Cost Institute (hat tip to David Anderson of Duke), is crystal clear about the reasons for the jumps in coverage and utilization. Chiefly, the launch of the individual exchanges resulted in a “surge of pent-up demand in both previously uninsured populations and previously uncovered services.”

President Trump was showered in praise Wednesday when he unveiled an initiative to fix the country’s wretched and ridiculously expensive system for dealing with kidney disease.

Simply put, many of the new entrants into the health coverage market had been uninsured “due to preexisting conditions,” which had resulted in their being refused coverage or offered insurance at inordinately high premium rates. The ACA, moreover, mandated coverage of conditions that previously had been routinely excluded from individual health plans, notably maternity services.

Before the ACA, insurers in the individual market charged women of childbearing age sky-high premiums for policies including maternity coverage, on the perfectly fair assumption that they would probably use it. That discouraged the entry of those women into the insurance market. “Similarly, male members or other members not likely to give birth would select individual coverages that excluded maternity so as to pay a lower premium,” the actuaries observe.

The contest for worst Cabinet member of the Trump administration is what we might call “competitive.”

Under the ACA, the cost of maternity care is spread among the entire insurance pool. That gives younger women more financial incentive to buy coverage. In effect, non-pregnant buyers subsidize pregnancy. Despite the idiotic posturing of conservatives (including President Trump’s own Medicare and Medicaid director, Seema Verma) that maternity coverage should be optional, this is plainly the proper policy, as the cost of propagating the species shouldn’t be imposed exclusively on women aged 18-45.

Finally, the actuaries’ report gives the lie to the claim of conservatives and Trumpians that they’re the guardians of consumers with preexisting conditions. Trump aired this canard most recently during his ghastly rally Wednesday in North Carolina, where it was sandwiched in among openly racist chants. Trump’s claim was that “patients with preexisting conditions are protected by Republicans much more so than protected by Democrats, who will never be able to pull it off.” Quite obviously, the Democratic-passed Affordable Care Act, which Trump is determined to destroy, brought those protections to consumers for the very first time. Trump would return the market to the exclusionary practices of the past.

Let’s look at the actuarial findings graphically.

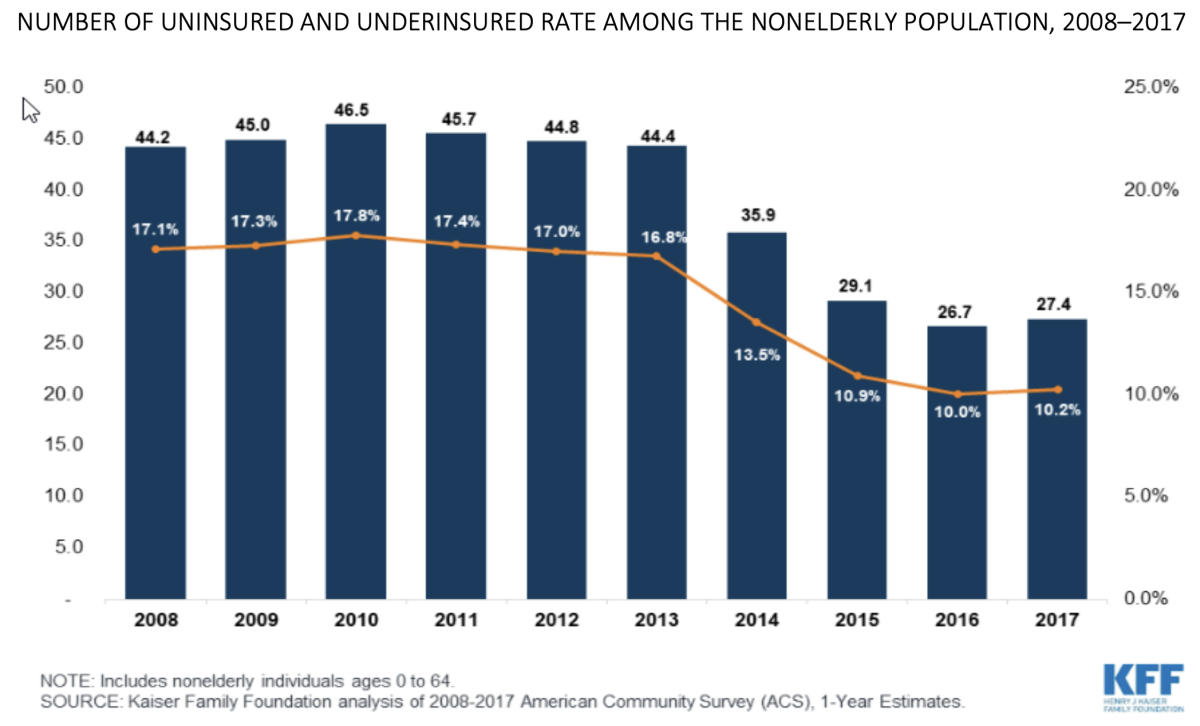

Starting with the view from 30,000 feet, the changes in the individual health insurance market brought down uninsured and underinsured rates starting in 2014. The rates have crept up starting in 2017, when Trump launched his efforts to undermine the Affordable Care Act.

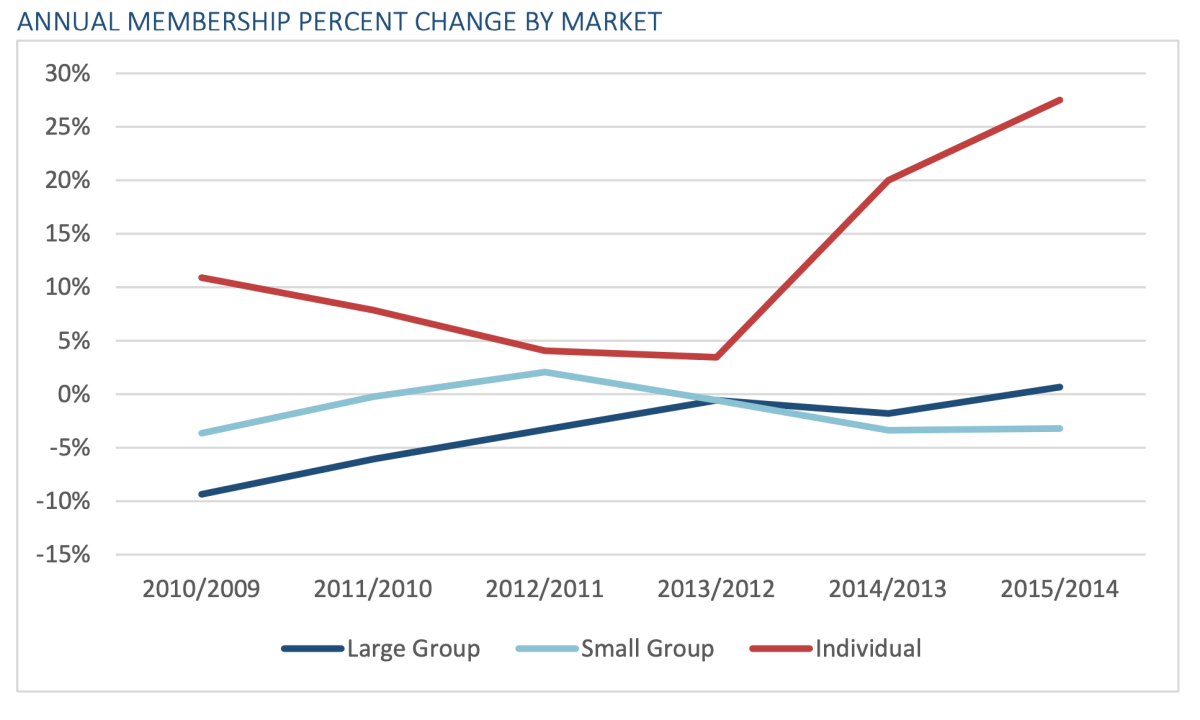

Membership in individual plans soared by more than 20% annually starting in 2014. Employer plans remained largely stable, with small-group plan growth falling slightly as members may have been shifted into ACA plans. Negative growth in the group market may have been a holdover from the recession.

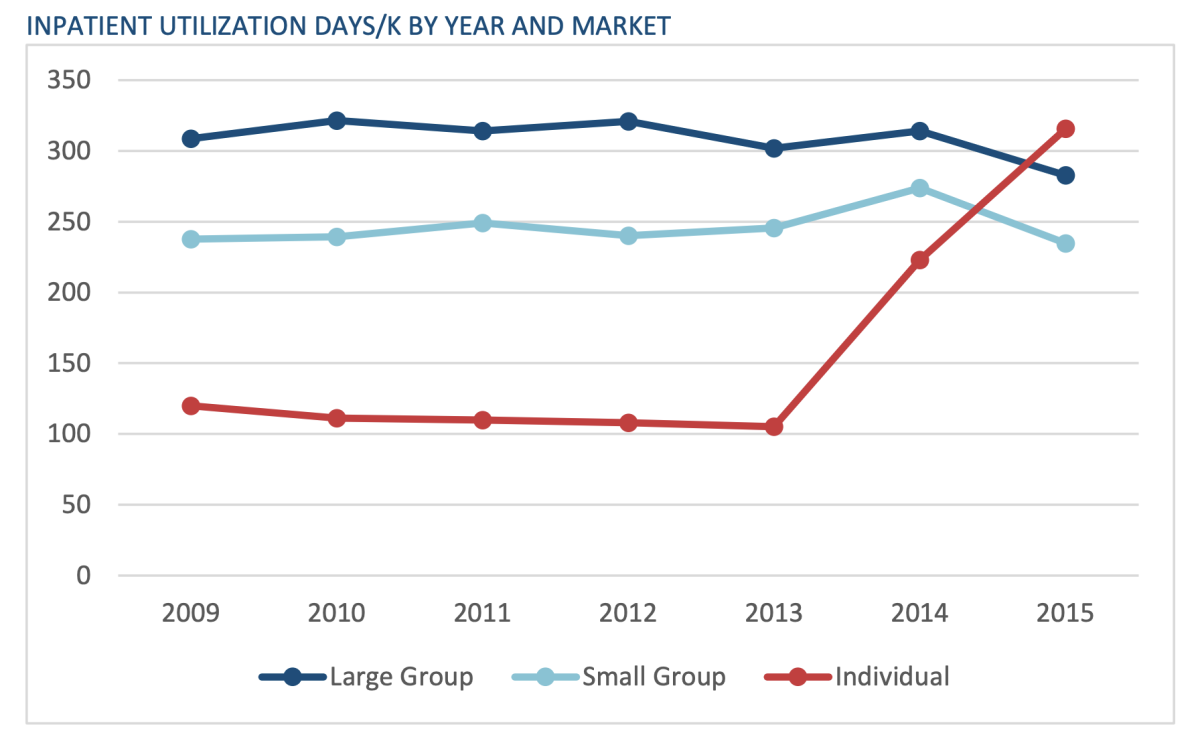

Inpatient stays per thousand members soared starting in 2014. This probably reflects the ACA’s mandated essential health benefits, which required coverage of maternity and behavioral health services for the first time. The actuaries observe that previously uninsured patients were “more likely to access inpatient services through the emergency department for high-acuity situations as their initial encounter with the health care system, especially if they had conditions that had been neglected.” This is an indication of the severity of the problem of lack of coverage for preexisting conditions before the ACA.

After the initial surge, the actuaries conjecture, the growth trend should flatten out “as members start to better control their chronic preexisting conditions through the utilization of other services and to establish relationships with primary care physicians.”

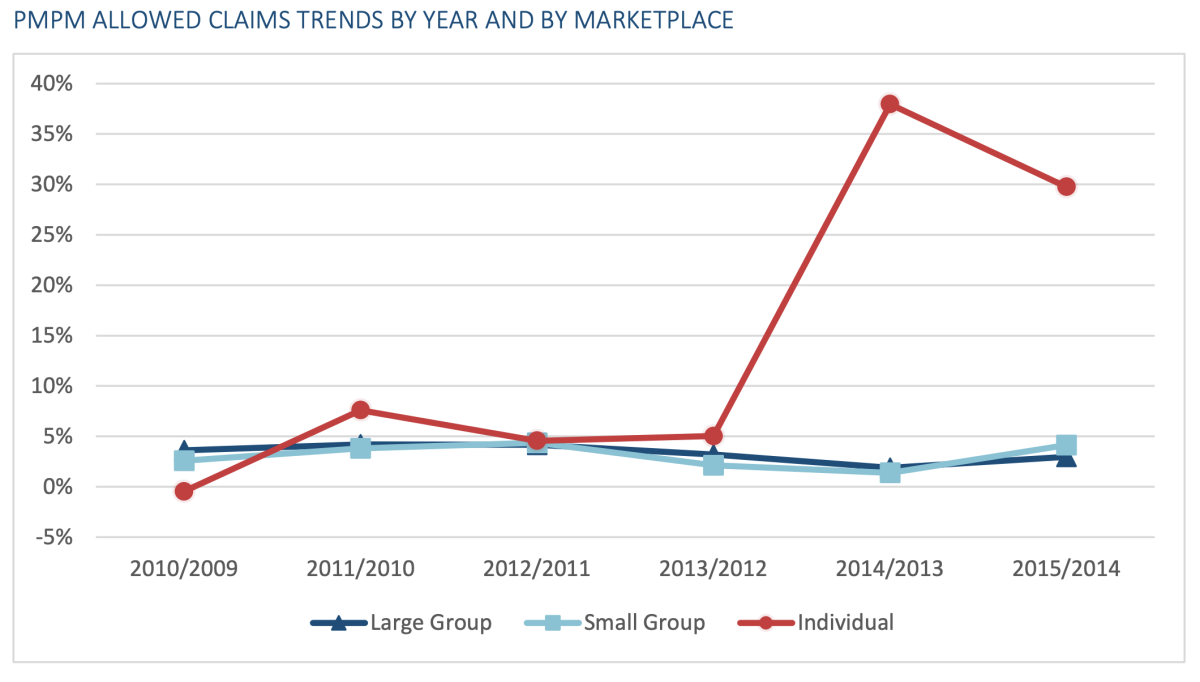

That seems to be the case according to the chart above, which shows the rate of increase in claims per member per month beginning to decline in 2015.

Duke’s Anderson makes a couple of pertinent observations about these statistics. He notices that small group and large group utilizations “tend to move in parallel to each other with large groups having slightly sicker or higher utilizing populations.” That’s to be expected, he says, because small employers have been less likely to offer insurance to employees, especially if they expect heavy utilization. (Think about a business employing lots of 20- and 30-year-old women, contemplating its maternity coverage claims.)

Anderson underlines the difference in inpatient rates between the individual market and the group markets before the ACA’s changes; individual plans saw as little as one-third the inpatient utilization as the group plans. That’s a testament to the efficiency of insurance company underwriting in the old days, when they kept people judged likely to need hospitalization out of the pool by refusing them coverage or pricing them out of the market. This is the supposed nirvana that Trump and the Republicans want to return to. It’s a world in which you can’t find affordable comprehensive insurance if a carrier finds even a history of hay fever in your record, but you can find a cheap policy that won’t cover any real medical needs.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.