California just wrapped up a banner water year. What’s on tap for the new one?

- Share via

Good morning. It’s Tuesday, Oct. 3. Here’s what you need to know to start your day.

- Just how watery was this past water year?

- Three momentous days in California

- Local pumpkin experiences that scream fall

- And here’s today’s e-newspaper

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

El Niño could bring more moisture to the state this winter

Happy new year! Well, new water year. California measures its annual precipitation cycle from October through the end of September, timed with the start of the wet season.

And we just wrapped up a banner year, with last winter’s epic storms bringing near-record rainfall and snowpack to much of the state, helping pull us out of a historic multiyear drought.

Just how watery was this past water year?

Over our just-ended water year, 33.48 inches of precipitation fell on California, according to the Department of Water Resources’ online tracker. That’s 141% of the state’s historical average. The Golden State ended the water year with 27.4 million acre-feet in its reservoirs, 128% of its historical average. And California’s snowpack, measured at the start of April, was phenomenal; it stood 237% higher than the historical average.

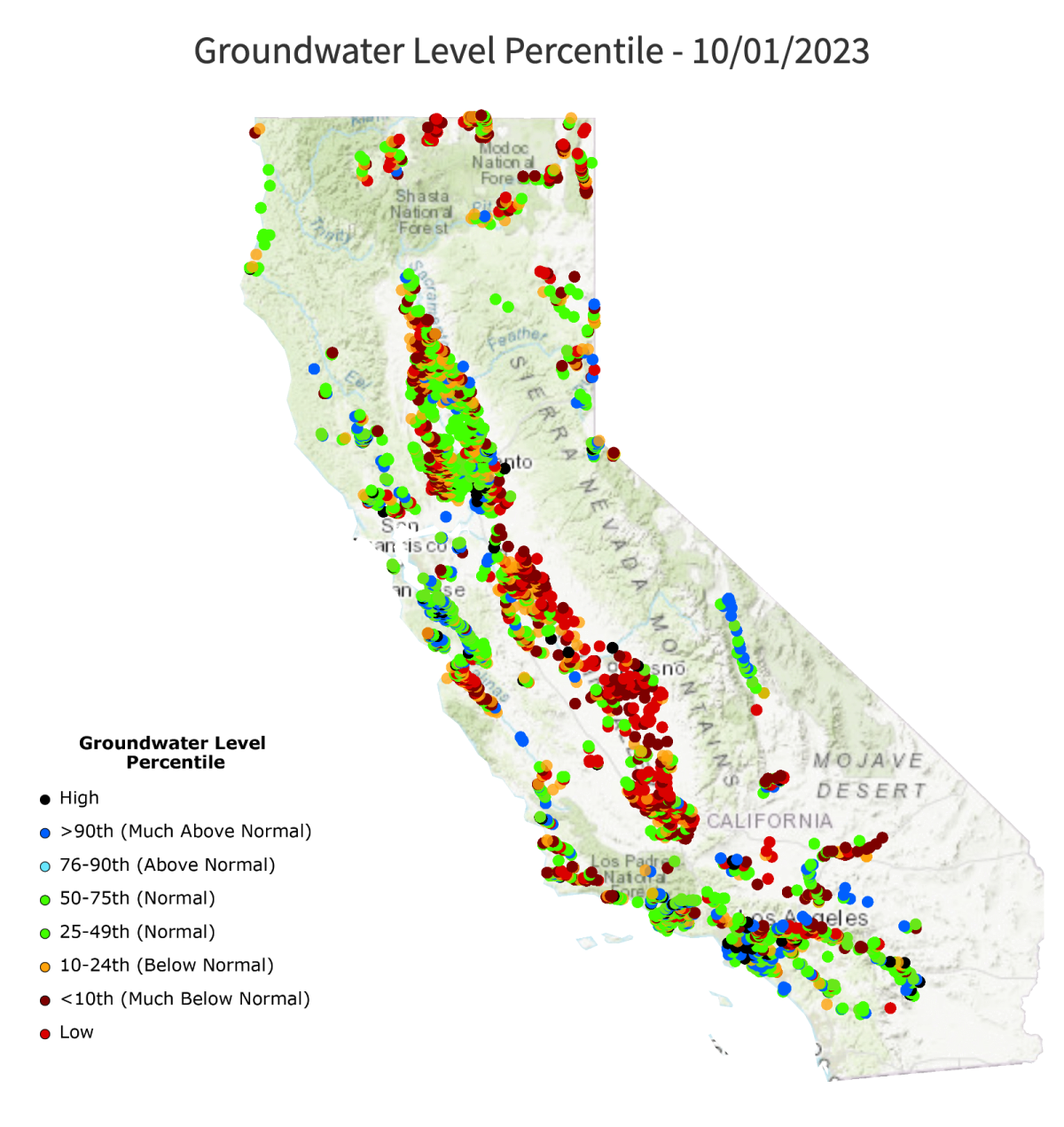

Another key water metric that’s not always visible is groundwater. The dousing the state got this past water year did give groundwater levels a boost but not enough to counter years of over-pumping and drought conditions that have left many underground aquifers dry or nearly dry. State officials report below-normal levels at 42% of the wells they monitor throughout the state. More than 400 wells have gone dry in the last year.

“In many ways, we couldn’t have had a better water year,” said hydroclimatologist Peter Gleick, co-founder and senior fellow of the Pacific Institute in Oakland.

Although there was severe flooding and damage in some regions, Gleick said it could have been worse, especially if we’d had a warmer spring that liquified our ample snowmelt too quickly. Then there was the “unusual summer water,” thanks in large part to Tropical Storm Hilary, which he said helped temper the heart of the state’s fire season.

Roughly 276,000 acres have burned in California so far this year. As my colleague Hayley Smith reported last week, that’s a considerable drop from the five-year average of 1,158,028 acres for the same year-to-date period, per the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. State officials warn that fire is a year-round threat — and new fuel growth and gusty fall winds keep that threat active.

Should we expect a similarly drenched 2023-24 water year — especially with the return of El Niño conditions, which tend to make for a wetter winter in Southern California?

Although Gleick can’t make any predictions about how much rain or snow California will get, he said El Niño conditions tend to bring more moisture to Southern California. Its impact, however, is “a little more ambiguous” on Northern California and the Sierra Nevada.

“That’s what’s critical for us,” Gleick said. “We really care about what’s happening in the mountains.”

He also noted that too much water falling too quickly could overwhelm reservoirs.

“Last year, they were empty,” he explained. “This year, the reservoirs are starting relatively full, and if we get as much water this year as we got last year, the risk of flooding is going to be more serious and more severe.”

As scientists, government agencies that manage our water and everyday Californians prepare for this new rainy season, Gleick mentioned three things worth paying attention to:

First: how our reservoirs operate in both wet and dry seasons. That means ramping up efforts to protect from flooding in the winter, but also being prepared to cut back during dry spells, Gleick said:

They’re still operated as though the climate isn’t changing. But we know the climate is changing.

Second: rethinking our approach to building in floodplains — and retreating from some entirely. That habit of developing near rivers and low-lying areas historically prone to flooding puts many California residents in jeopardy, Gleick said.

“We’re going to have to move people [and] infrastructure out of floodplains,” he told me.

Third: getting better at turning stormwater into groundwater. California’s urban areas let between 770,000 and 3.9 million acre-feet of water spill away annually (depending on how dry or wet the year is), according to the Pacific Institute.

Water officials are trying new methods to replenish dried out aquifers, Gleick said, “letting rivers flood lands in the winter, so that water can be recharged.” But he noted those efforts need to be more comprehensive.

He’s hoping for another wet year, but Gleick said that in his many years studying water in California, he’d learned not to make predictions.

“Nature always surprises us,” he said. “And as climate change has accelerated, nature brings more and more surprises.”

Today’s top stories

Three momentous days in California politics

- How we got from Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s death to the rise of Laphonza Butler.

- Incoming Sen. Laphonza Butler describes her whirlwind trip into California history.

- The public is invited to pay its respects to Feinstein this week as her body lies in state at San Francisco City Hall.

In the county and the city

- If Los Angeles adds City Council seats, how would it work?

- Twelve L.A. County cities sue to postpone the new zero-bail policy.

Education

- Federal student loan payments resume this month. Here’s what you need to know.

- Claremont McKenna raises $1 billion, among the largest hauls ever for a liberal arts college.

Actors’ strike

- SAG-AFTRA and studios to meet for a second day in talks to resolve the actors’ strike.

- After the WGA declares victory, what will SAG-AFTRA win from the studios?

More big stories

- Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh has become an unexpected check on the Supreme Court’s sharp move right.

- Rep. Matt Gaetz moves to oust Kevin McCarthy from speakership.

- California lawmakers have a plan to plug old, vapor-spewing oil wells. Could it backfire?

- Latino Theater Company gives out millions in grants to boost Latino theaters nationwide.

- The families of the Marines killed in a crash seek the prosecution of an L.A. County deputy.

- After drizzles, temperatures will move toward triple digits in Southern California.

- Huge strike could happen at Kaiser hospitals starting Wednesday. Here’s what we know.

- Russia aims to bring winter — and blackouts — early to Ukraine with attacks on its power grid.

Get unlimited access to the Los Angeles Times. Subscribe here.

Commentary and opinions

- Mary McNamara: Dear SAG-AFTRA, don’t feel pressure to make a deal. This contract is too important.

- Mark Z. Barabak: A solid Senate pick and a craven move by Gavin Newsom.

- Editorial Board: L.A.’s broken government needs change. Voters shouldn’t have to wait until 2032 to get it.

Today’s great reads

Saving Mt. Wilson Observatory: Inside the long battle to maintain the spot where we found our place in the universe. The most important things we know about the cosmos were discovered in the mountains above Los Angeles. “You don’t just throw away a historic place,” says one of the volunteers trying to save it.

Other great reads

- After approving a settlement requiring L.A. County to provide 3,000 new mental-health and substance-use treatment beds, Judge David O. Carter staged a test.

- ‘He’s just very much on a mission’: Family fuels Solomon Byrd’s USC breakthrough.

- Fallen from the middle class: 60, living in an RV and fighting to be housed

How can we make this newsletter more useful? Send comments to essentialcalifornia@latimes.com.

For your downtime

Going out

- 🎃 16 L.A. and O.C. pumpkin experiences that scream fall.

- 🎤 OK, moviegoers, now let’s get in formation. Beyoncé’s Renaissance movie hits theaters in December.

- 🍸 The best places to eat and drink in L.A. right now, according to our food writers.

Staying in

- 📚 Don’t fear the bears! Mammoth’s ‘bear whisperer’ will teach you how to coexist.

- 🧑🍳 Here’s a recipe for Big & Boozy Panna Cotta.

- ✏️ Get our free daily crossword puzzle, sudoku, word search and arcade games.

And finally ... a great photo

Show us your favorite place in California! Send us photos you have taken of spots in California that are special — natural or human-made — and tell us why they’re important to you.

Today’s great photo is from Karthik Prasad of Los Angeles: Los Padres National Forest from the Santa Barbara waterfront. Prasad writes: “The picture was taken on May 6, 2023, a nice & sunny day.”

Have a great day, from the Essential California team

Ryan Fonseca, reporter

Elvia Limón, multiplatform editor

Amy Hubbard, assistant editor

Karim Doumar, head of newsletters

Check our top stories, topics and the latest articles on latimes.com.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.