To understand California wildlife, researchers study roadkill. Here’s what it tells us

- Share via

Good morning. It’s Thursday, Oct. 12. Here’s what you need to know to start your day.

- Here’s what roadkill data tells us about California wildlife

- Space shuttle Endeavour’s rockets roll into L.A.

- $50 tickets and everything else that’s new at Disneyland this fall

- And here’s today’s e-newspaper

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Roadkill data is shaping our understanding of California’s wildlife

I’ve written a decent amount about the effects our car-centric culture has on public safety, air pollution, housing and sprawl. But driving doesn’t harm just humans: collisions with cars kill massive numbers of wild animals every year.

Understanding just how much wildlife California drivers kill is giving researchers a sense of how some species’ populations are changing — and why.

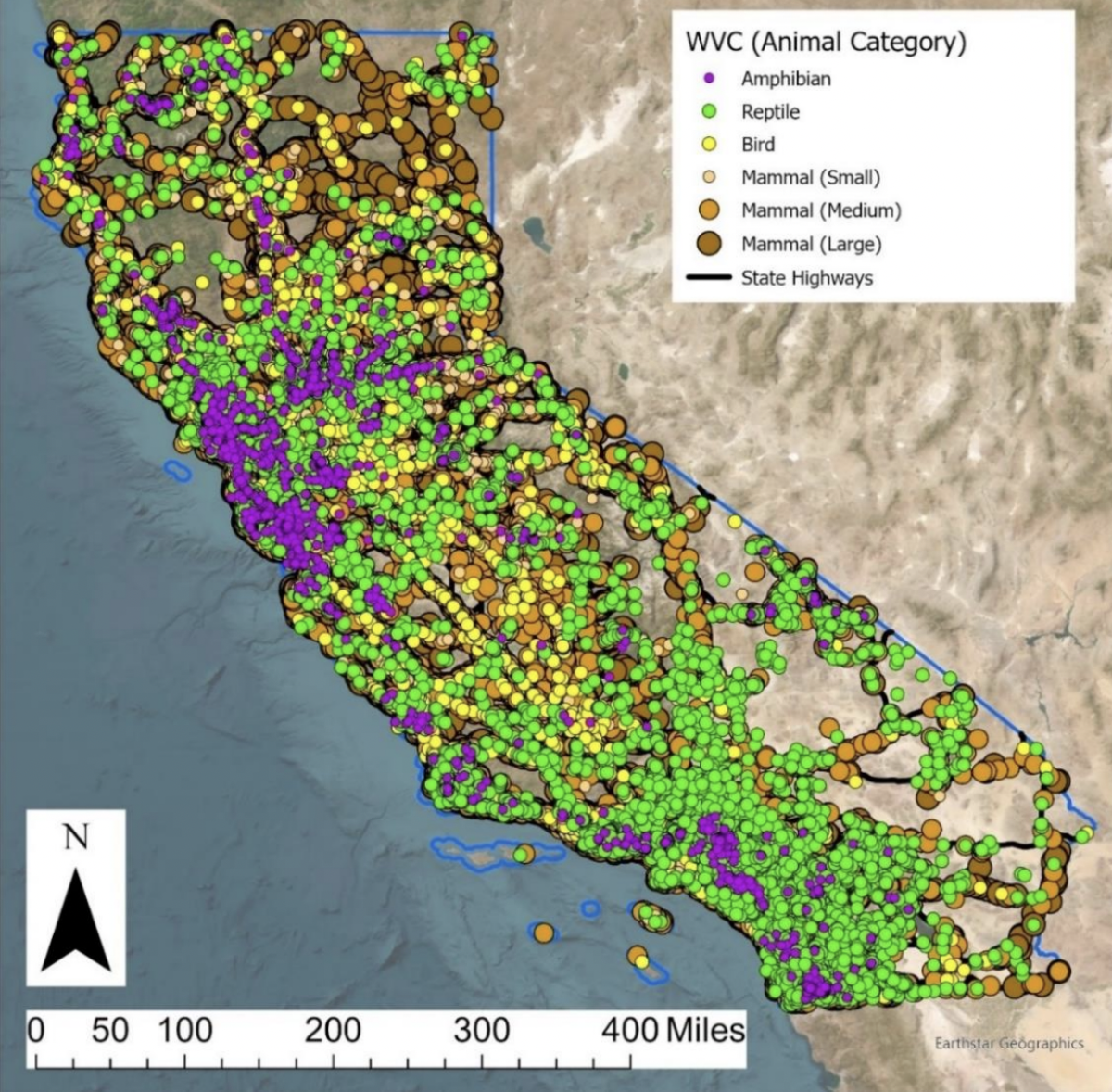

The Road Ecology Center at UC Davis attempts to quantify the effect our driving has on wildlife in its annual roadkill report. Its most recent findings, released in late September, point to “excessive rates of traffic collisions” as one possible factor in the population decline of some of the Golden State’s iconic wildlife.

(Fair warning: there are images of dead animals in the report.) The 2023 report also maps out roadkill hot spots across the state. But it’s much easier to spot the few regions where animals aren’t being regularly killed.

Researchers compiled reporting from 2009 through 2022, which showed that more than 173,000 species of mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians were killed on roads across California. And that’s just the number of deaths reported by state agencies, by the public to an online database and to insurance companies. The actual death toll is higher, since not everyone who hits or kills an animal with their car reports the collision.

Fraser Shilling, director of the Road Ecology Center, said one purpose of the report is to identify “looming threats, in some cases before they become significant.” He explained another reason the roadkill report is so important:

“[California] doesn’t monitor wildlife populations very well… one way to do that is to monitor their deaths, unfortunately, but it helps give us an idea of where the wildlife populations are heading.”

One of the key findings from the latest report is that the number of mule deer killed on state roads fell by 10% annually over the last seven years. That may seem like a good thing, but that would be giving drivers too much credit. The report indicates that the mule deer population is shrinking, meaning there are fewer for drivers to potentially strike.

The number of coyotes killed fell as well, which also points to population decline, the report states. That was surprising, Shilling said, because of how well coyotes have adapted to human-built environments. And taken together, those population decreases are a cause for concern, he explained:

“Deer and coyote are really quite different in their behaviors, what they eat, [and] their place in the ecosystem. The fact that they both went down is troubling because it suggests a larger ecological problem.”

And fewer deer and coyotes have a ripple effect on California’s mountain lions, which eat both species.

“There’s just fewer of their prey to find, so they have to move longer distances to find them,” Shilling said. “If they move longer distances, they’re going to cross more roads and there’s more chance they’re going to be hit by a car.”

Traffic collisions are a primary source of human-caused wildlife deaths, Shilling noted. Earlier this year, he mapped out fatal collisions of mountain lions, reporting that drivers were killing the pumas faster than they can reproduce.

And of course Los Angeles’ own beloved celebrity cougar, P-22, was euthanized last December, in part due to injuries he suffered after being hit by a car.

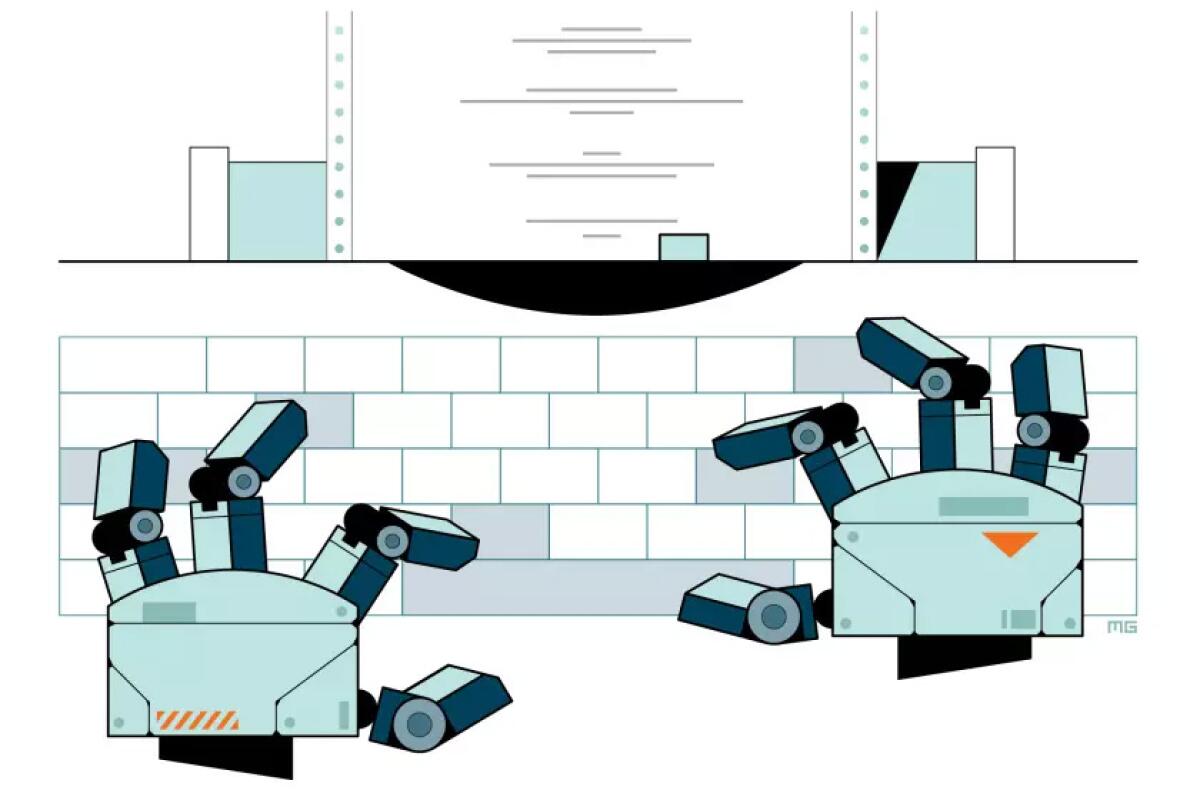

California and other states are adopting some solutions to keep animals off roadways, including fencing, and safe crossing sites, such as the wildlife bridge under construction across the 101 Freeway in Agoura Hills.

Last year, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed into law the Safe Roads and Wildlife Protection Act, which directs Caltrans to make wildlife protections a priority when it plans new road projects.

Another solution noted in the Road Ecology Center’s report: lowering speed limits considerably in state parks and other roads that run through wildlife habitats.

Shilling said investments such as crossings and fencing would have been more impactful 20 years ago; the solutions we implement now “have to be more rigorous.”

For him, that means rethinking “how we’re driving and whether we drive at all,” especially since our culture centered on driving our cars mostly everywhere and mostly at our own discretion “is one of the biggest causes of environmental degradation in the world.”

“It’s just like climate change,” Shilling said. “You have to start to make these choices. If you want to protect the environment — for your own generation or for future generations — the things you have to do are becoming more significant.”

Today’s top stories

- Space shuttle Endeavour’s rockets roll into Los Angeles as the Science Center hails their arrival.

Politics

- At far-right roadshow, Trump is God’s ‘anointed one,’ QAnon is king, and ‘everything you believe is right.’

- California Republicans are hoping Steve Garvey is in a league of his own.

- Senators draft policy aimed at ‘deep fakes’ of Drake, Tom Hanks and noncelebrities.

Crime and courts

- Former NFL player Sergio Brown was arrested in San Diego on suspicion of his mother’s murder.

- Noncitizen parents will again be able to vote in San Francisco school board elections after a conservative group drops a legal fight.

- The U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals stays a ruling overturning California’s ban on high-capacity ammunition magazines.

- The Moreno Valley school district was hit with a $135-million verdict in a molestation case.

California businesses

- Disneyland announces another round of price hikes in time for the holiday season.

- Waymo’s driverless taxi launch in Santa Monica is met with excitement and tension.

Climate and environment

- Spiders, spiders everywhere? Tarantula mating season starts early amid threats to arachnids.

- California grants protection for a rare cliff-dwelling daisy amid outcry over a mining operation.

Entertainment

- SAG-AFTRA, studio negotiations break down. Gap ‘too great,’ AMPTP says.

- Horrific images from Israel-Hamas war pose challenges for TV news.

- She went from ‘Munch’ to Munchkins in a New York minute. But Ice Spice is just getting started.

- Taylor Swift’s Eras tour concert film shuts down The Grove.

- Cher denies the ‘rumor’ that she orchestrated a plot to kidnap her son during his contentious divorce.

- Dolly Parton reveals her preacher grandfather ‘whipped’ and ‘scolded’ her for her fashion choices.

- Meet the man who shot both ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’ and ‘Barbie.’

More big stories

- $1.73-billion Powerball ticket sold in Frazier Park, second-highest jackpot ever.

- How the carpenters’ union broke the California logjam over new housing laws.

- It’s time to get your COVID shot, the CDC director says. Like, now.

- L.A.’s close-knit Israeli dance-music community mourns deadly attack on Supernova rave.

- UCLA vs. Oregon State: One rivalry where the Bruins always gave a dam.

Get unlimited access to the Los Angeles Times. Subscribe here.

Commentary and opinions

- Bill Plaschke: Splat! Humiliated Dodgers swept into next season.

- Opinion: Why Sam Bankman-Fried’s aversion to ‘grownups’ probably will prove to be criminal.

- Opinion: What Gov. Gavin Newsom could learn from China’s response to climate change.

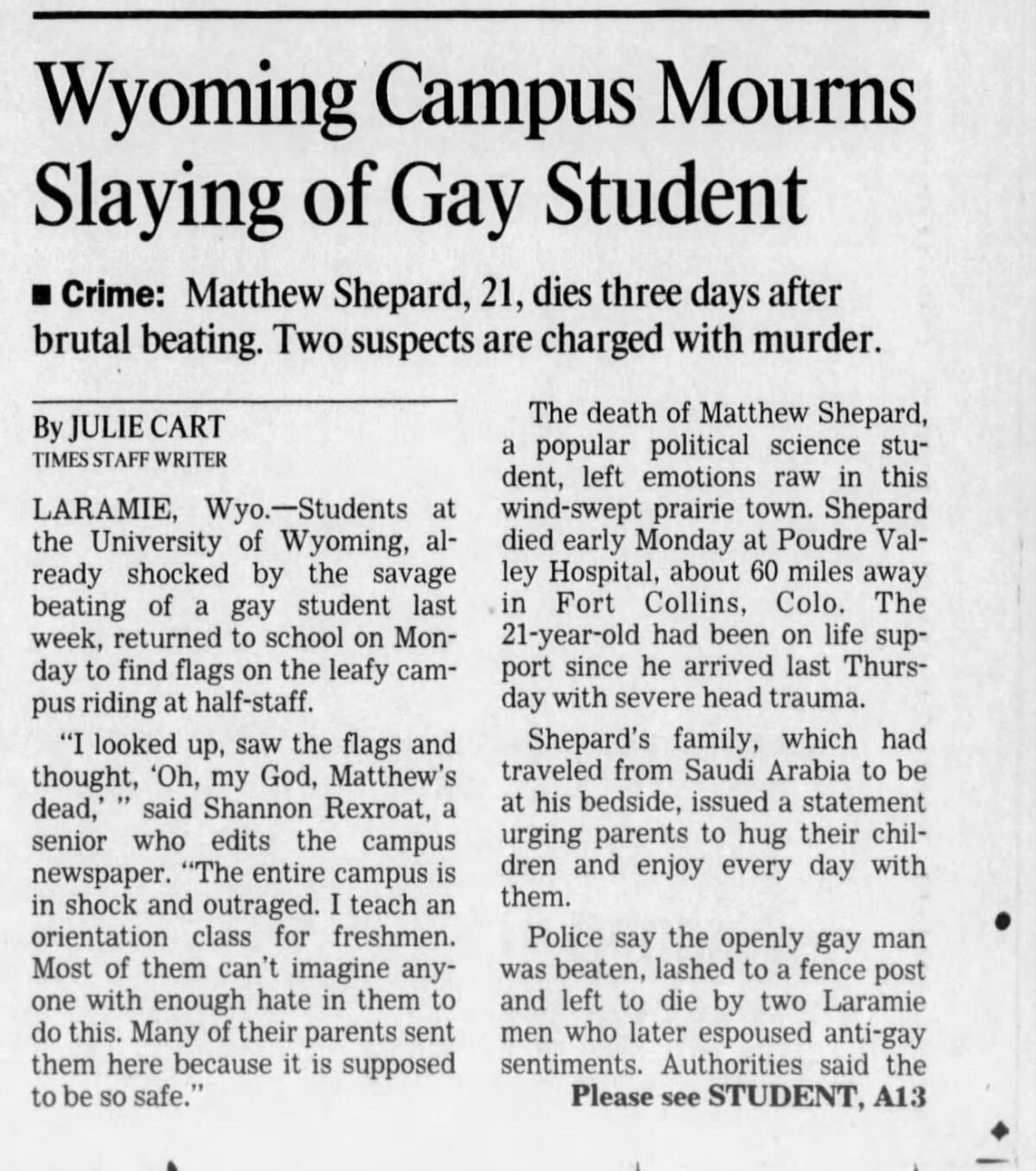

- Opinion: As LGBTQ+ rights are challenged, Matthew Shepard’s story is more vital than ever 25 years on.

- Suzy Exposito: Here’s what happened when Bad Bunny judged a ‘Shark Tank’-style competition for Latino businesses.

- Carolina A. Miranda: The Las Vegas Sphere interior’s first film is both mind-blowing and Disneyfied.

Today’s great reads

Can you tell which script was written by AI? How useful will artificial intelligence actually be for writers who want its help generating ideas or sharpening drafts? And if they do use it, will viewers at home be able to tell? To put these questions to the test, The Times compiled a series of excerpts from various unproduced scripts and screenplays. Can you tell which ones a human wrote and which were machine-made?

Other great reads

- NASA shows off its first asteroid samples delivered by a spacecraft.

- More than 1 in 7 men have no close friends. The way we socialize boys is to blame.

- Joan Baez on facing trauma, her Bob Dylan epiphany and belonging to the ‘no facelift’ club.

How can we make this newsletter more useful? Send comments to essentialcalifornia@latimes.com.

For your downtime

Going out

- 📚 How L.A. libraries are supporting the next generation of Latino authors.

- 🎡 $50 tickets and everything else that’s new at Disneyland this fall.

- 🥪 A critical breakdown of Costco’s new food court items.

Staying in

- 💿 The cowgirl, the ’70s and Friday the 13th: Here’s what to know about Bad Bunny’s new album.

- 📺 Why sports are returning to free over-the-air TV.

- 🖥️ Watch Olivia Rodrigo perform at L.A.’s Theatre at Ace Hotel from the comfort of your own home.

- 🎥 ‘Messi Meets America’ docuseries shows in-depth look at his move to Miami.

- 🍋 Here’s a recipe for coco limonada.

- ✏️ Get our free daily crossword puzzle, sudoku, word search and arcade games.

And finally ... from our archives

On this day 25 years ago, college student Matthew Shepard died several days after being beaten, lashed to a fence post and left to die by two men in Laramie, Wyo., who later espoused anti-gay sentiments. Shepard’s sexual orientation was believed to have motivated the attack, and his death contributed to the expansion of federal hate crime legislation.

Have a great day, from the Essential California team

Ryan Fonseca, reporter

Elvia Limón, multiplatform editor

Kevinisha Walker, multiplatform editor

Laura Blasey, assistant editor

Check our top stories, topics and the latest articles on latimes.com.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.