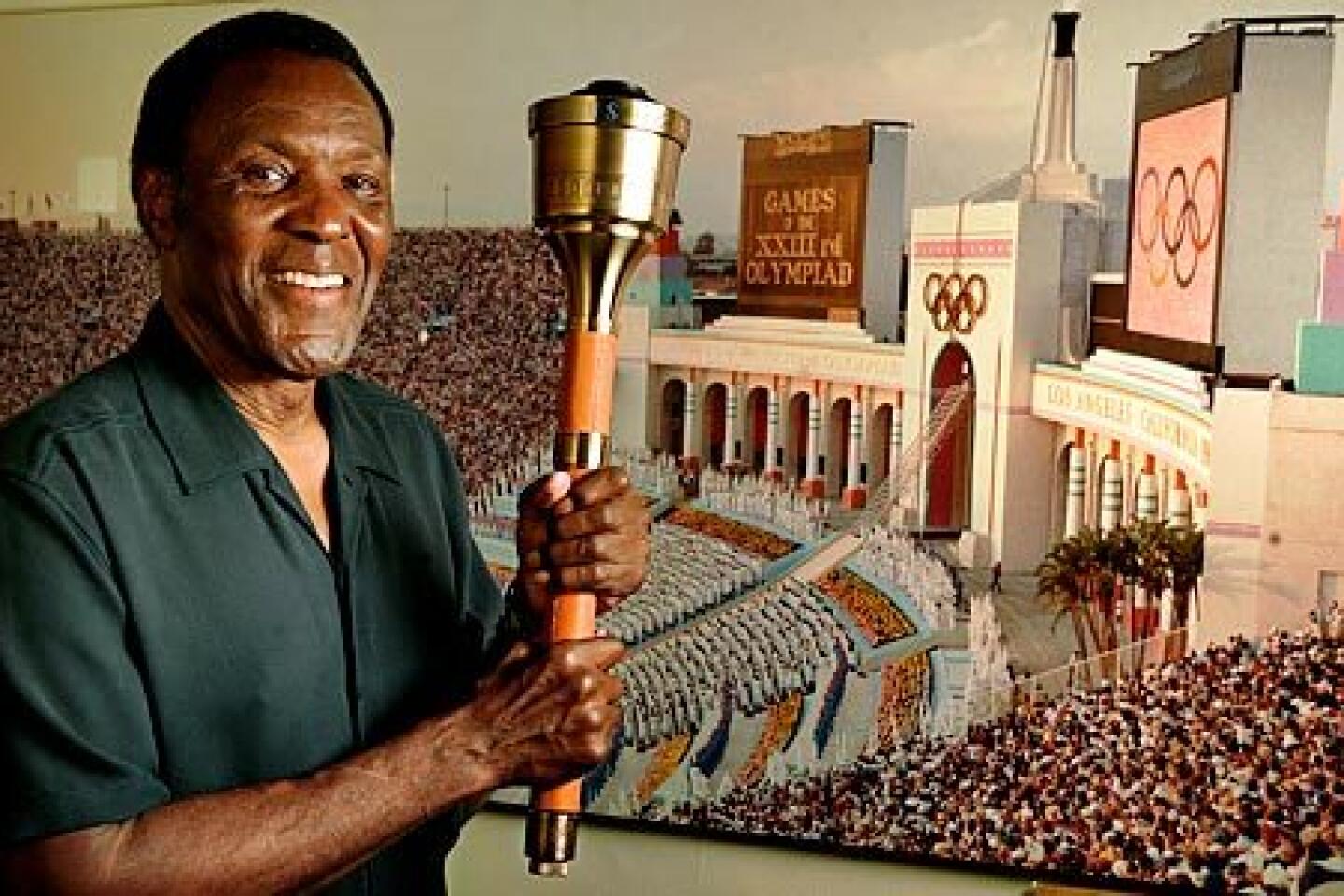

Dave McCoy, who gave skiers and boarders Mammoth Mountain, has died at 104

Dave McCoy has died at age 104.

- Share via

Dave McCoy, a towering pioneer of the California ski industry, who with vision, hard work and a knack for the mechanical transformed a remote Sierra peak into the storied Mammoth Mountain Ski Area, has died. He was 104.

A notice of McCoy’s death posted Saturday afternoon on the Mammoth Mountain website simply said, “Thank you, Dave McCoy, for everything.”

Rusty Gregory, former chief executive at Mammoth Mountain, said McCoy “died peacefully in his sleep” at his home in the eastern Sierra Nevada community of Bishop, Calif.

“I was shocked by the news of his passing,” Gregory said. “Yes, he was on in years. But he was such a force of nature that it was hard to accept. Dave was Mammoth Mountain.”

The mountain, about 300 miles north of Los Angeles, off Highway 395, was the hub of McCoy’s life for more than six decades. In his hands, it grew from a downhill depot for friends to a profitable, debt-free operation of 3,000 workers and 4,000 acres of ski trails and lifts at Mammoth and June mountains, a haven for generations of skiers and boarders

Mammoth was one of the three most-visited ski resorts in 2018, drawing about 1.21 million skiers and boarders, most of whom drove there on weekends from Southern California.

“McCoy was part of a post-World War II cohort of pioneers who had an extraordinary sense of what they could do, which is why we have a place like Mammoth Mountain today,” said Hal Clifford, executive editor of Orion, a nature and culture magazine. “It’s a unique creation that wasn’t hatched in a corporate planning room or a focus group.”

Bob Roberts, spokesman for the California Ski Industry Assn., described McCoy as a “visionary who was pivotal in the development of the sport in the West.”

“McCoy’s passion literally grew out of the snow,” Roberts said.

Born Aug. 24, 1915, in El Segundo, McCoy was the son of a nomadic paving contractor with a passion for machinery. His parents separated when he was in his teens.

Shortly after graduating from high school, he moved to Independence, an eastern Sierra hamlet where they still talk about his speeding along Highway 395 on a brown and yellow Harley Davidson with a red bandanna tied around his head.

Lashed to the side of that motorcycle were skis he carved from ash wood.

McCoy bent the tips with steam from a boiler at a mine where his grandfather worked. He strapped them to his logging boots with strips of inner tube.

As a young man, McCoy picked grapes, tended pigs, sold firewood and tied flies for fishermen. Judging from photographs taken of McCoy at the time, he enjoyed skiing in T-shirts and jeans, or even shirtless.

McCoy was working as a soda jerk at a restaurant in Independence when he first laid eyes on his future wife, Roma.

“She was in a group of cheerleaders, and they’d stopped to get sodas,” he recalled in an interview in early 2005. “I knew right then and there, she was the right girl for me. They don’t make them like her anymore.”

In the late 1930s, McCoy landed work as a snow surveyor for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. As a city hydrographer, he concluded that skiing didn’t come any better than on the massive extinct volcano with steep chutes on all sides that caught storms like a sail.

“David McCoy’s LADWP career is the stuff of legend,” Martin Adams, chief engineer and general manager of the DWP, said Saturday. “David’s significant contributions to LADWP’s storied history and to the ski community worldwide cannot be overstated.”

In 1937, McCoy parked his Ford Model A on a slope where snow fell early and hard on Mammoth Mountain. He jacked up the rear of the car and lashed one end of a rope to the back wheel and the other to a tree.

He charged 50 cents a person for what became the first rope tow on the mountain, which usually has skiable snow from early November to early summer.

With the help of friends, McCoy worked through blizzards, droughts and economic downturns, building increasingly sophisticated machinery to pull skiers up the mountain and groom the snow.

Dave and Roma married in 1941 in Yuma, Ariz., and then moved into a single-room house in Bishop, an hour outside Mammoth. They opened a mom-and-pop ski business, using one of his motorcycles as collateral to buy a used portable rope tow for $86.

McCoy secured a year-to-year permit from the U.S. Forest Service to run a portable tow anywhere in the eastern Sierra between Bridgeport and Bishop.

Still, no one but McCoy envisioned Mammoth, which then was home for no more than a dozen permanent residents, as a major resort.

“People told me it snowed too much,” he recalled in an interview with The Times. “It was too stormy, too high and too far away.” The McCoys stashed their rope tow proceeds in fishing creels and cigar boxes. Occasionally, they traded lift rides for staples.

In 1942, McCoy was racing downhill in a state championship when he crashed, shattering the bones in left leg. Doctors wanted to amputate, but McCoy wouldn’t listen. His injuries, along with his work as a government hydrographer, exempted him from military duty during World War II.

The 1942 accident was only one of many serious spills on the slopes and on his motorcycles and mountain bikes. At age 87, McCoy lost control of his motorcycle and spent a month in the hospital.

After World War II, Southern California saw an explosion of interest in skiing. But building a top-notch ski resort at Mammoth Mountain still seemed only a dream when McCoy envisioned a diesel-powered tow that could move 1,800 skiers an hour.

Warren Miller, the late ski video producer and an old friend, recalled how skiers liked to josh that after hanging onto McCoy’s tows for a few weekends, their right arms would be an inch longer than their left.

Freezing in a cramped trailer, shooting rabbits for dinner, slurping a gruel of ketchup and oyster crackers: Warren Miller’s early 20s would have been downright Dickensian if they weren’t so much fun.

“Dave led a hearty band of pioneers,” Miller said. “When a rope tow started wearing out, he’d shut it down, get out some tools and fix it himself. If the tow engine was running low on fuel, he’d get some up there by holding onto the rope tow with one hand and a five-gallon can of gas with the other.”

Over the ensuing decades, the amiable McCoy cleared land, laid concrete, raised ski lift towers, maneuvered cranes and frequently stood in line at his ski lifts to overhear what his customers had to say about what worked and what didn’t.

Many of the operation’s special tools, cranes, rigs, engines and snow cats were built from scratch in McCoy’s garage, where he spent long hours experimenting with new designs and modifying available machinery.

In 1955, within only three months — and 30 days ahead of schedule — Mammoth Mountain erected a high-capacity double-chair lift that was 3,400 feet long with a vertical rise of 1,000 feet. The lift’s 86 double chairs, which were diesel-driven, carried 900 skiers an hour — at the time, the largest lift of its kind in the state.

In the adjacent community of Mammoth Lakes, McCoy and his staff launched a water district, volunteer fire department, regional hospital, high school, skiing museum and college.

Untold numbers of people received employment, financial help, even property from McCoy over the years. But much of what the reserved ski operator did for others went unpublicized.

“If he liked someone and felt they had a positive contribution to make, he’d help them out,” said Benett Kessler, the late owner of Bishop’s Sierra Wave radio and television station, who often went to McCoy for advice and moral support over the years.

McCoy was loved by local families, who for decades enjoyed a variety of special privileges such as cut-rate lessons and skiing passes for children.

McCoy also coached legions of hardcore ski competitors and young racers, some of whom made U.S. Olympic teams. Among them was Robin Morning, who is now writing a biography of McCoy titled “Tracks of Passion.”

“We skied all day long with him — he kept us moving — and he really believed that everything should be fun,” said Morning, who was a member of the 1968 team.

In 1972, Mammoth took over Sierra Pacific Airlines, which flew 54-seat Convairs from Los Angeles, Burbank, Fresno and Reno directly to Mammoth Lakes’ airport until 1978. It was sold to reduce costs following a series of drought years.

Around this time, Mammoth’s ski patrol walked off the job after one ski area employee was killed and another lost a portion of his hand from accidental explosions during avalanche control work. McCoy and one of his employees completed the perilous work, detonating charges on cloud-covered, windy mountain peaks.

As the operation mushroomed into a full-scale resort, critics complained that McCoy spent too much time fine-tuning the mountain and not enough on improving local amenities. As a result, Mammoth struggled with a nagging image as an everyman’s “Sears, Roebuck” resort of cheap rooms and fast-food lunches.

In the early 1990s, facing a prolonged drought, a volcano scare and a recession, McCoy was forced to lay off 150 employees, some of whom had worked on the mountain for decades.

To stave off bankruptcy, Mammoth installed extensive snow-making machinery that could guarantee a Thanksgiving Day opening.

In 1996, Vancouver-based Intrawest Corp. bought a significant stake in the operation and moved to make the area more upscale by building a Craftsman-style hub of lodging, entertainment and shopping called the Village at Mammoth.

In October 2005, McCoy announced plans to sell a controlling interest in the resort to Starwood Capital Group for $365 million — then the largest ski resort sale in history.

At one point during the signing of more than 100 pages of documents believed to have brought him $80 million, McCoy openly wept.

Later that day, McCoy sat in his office, wistfully surveying hundreds of awards, plaques and photographs of him skiing down the slopes, overseeing construction projects or caked with mud after off-roading competitions.

“We did something here that everyone said would be impossible,” he said.

Asked how he and his wife planned to spend that evening, he smiled and said: “The way we always do: We’ll go home, have dinner and watch the sunset. If it’s beautiful, I’ll take a picture of it.”

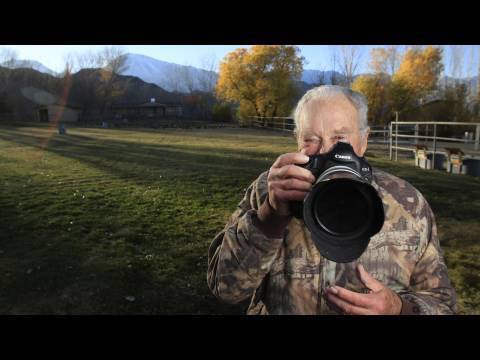

At 94, McCoy found a new calling as a photographer, tirelessly prowling the eastern Sierra’s backcountry roads several times each week on an all-terrain vehicle known as a Rhino, toting an array of sophisticated cameras he called “my six-shooters.”

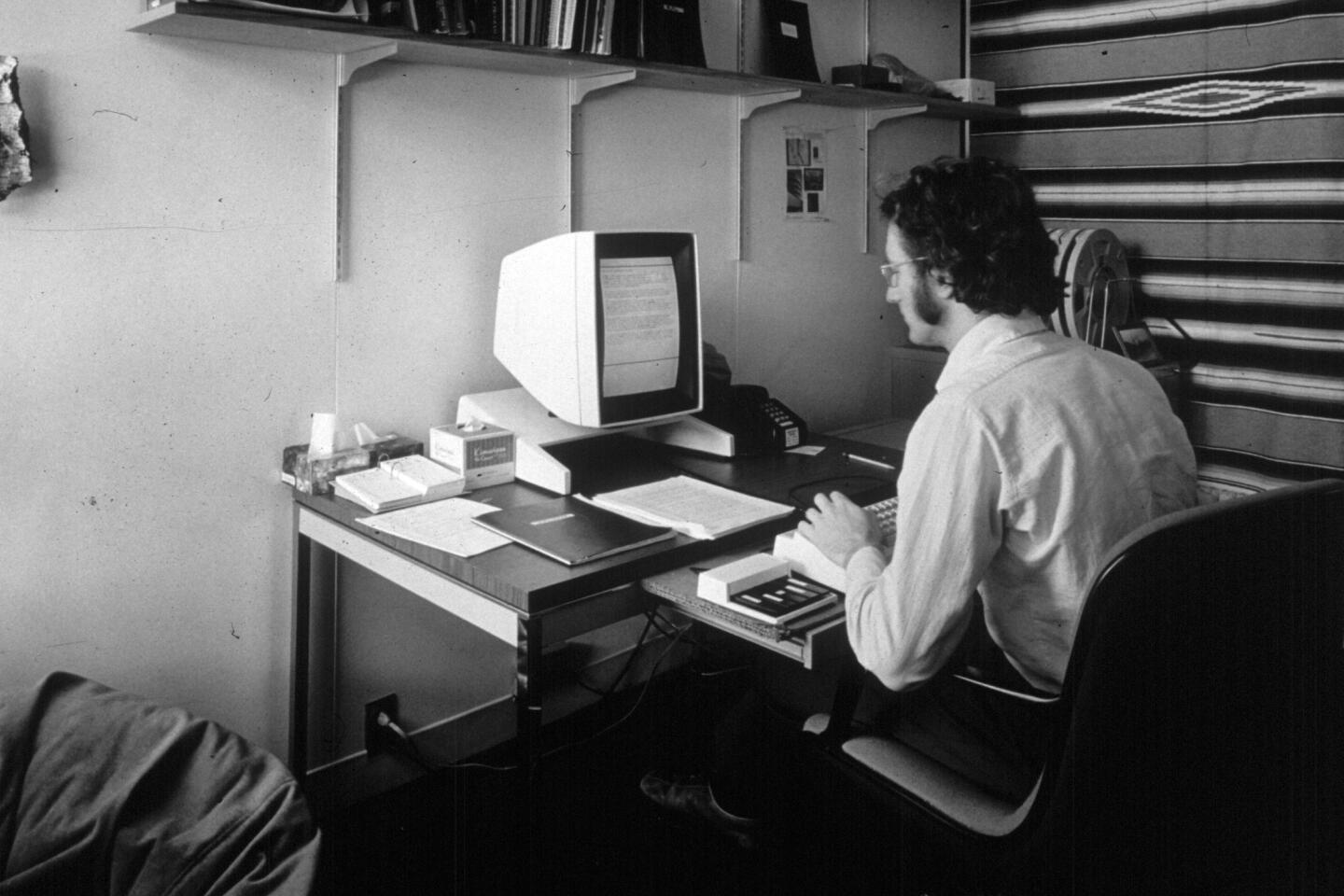

Over the years, McCoy archived hundreds of thousands of photographs on his home computer attached to a 52-inch television monitor used to critique and modify the images.

They were mostly of wildlife and vistas he’d known since childhood: Mammoth Mountain’s long, open slopes, cloud formations over the White Mountains, iris blooms in spring meadows, 13,649-foot Mt. Tom, cottonwood and birch trees, sagebrush, snow-fed streams, waterfalls and boulders sculpted by rain and wind until they resembled walruses, bears and human faces.

Personal favorites included an “angel in the sky” cloud formation taken in 2008 while he and Roma were off-roading a few miles from home.

“I looked up,” Roma recalled, “and noticed wisps of clouds shifting over the White Mountains. I grabbed Dave’s arm and said, ‘Stop! We’ve got an angel up there.’ ”

McCoy aimed his telephoto lens and waited. “I saw her taking shape,” he recalled. “First her body, then her athletic thighs and legs. Then came the wings and arms. Then she seemed to be carrying a torch. I took the picture.

“I still don’t understand that picture, though,” he said. “It must mean something.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.