- Share via

RICHMOND, Calif. — By all accounts amid this pandemic, the city of Richmond should be sitting at the precipice of disaster.

Situated between the Berkeley Hills and the San Francisco Bay, Richmond is a densely populated community predominated largely by people of color, high unemployment and a large transient population.

For the record:

4:43 p.m. April 25, 2020The original version of this story misstated the unemployment rate in Richmond. As of March, it was 4.3%. The percent of population below the poverty line was around 15%.

Its roughly 110,000 residents have limited access to emergency healthcare, and they live in the shadow of a Chevron refinery and just down the road from four others — increasing their chances of respiratory distress, a risk factor for people sick with COVID-19.

So far, however, Richmond hasn’t seen the kind of outbreaks documented in other parts of Contra Costa County. Community advocates think there is a reason for that. There’s been little testing in Richmond and other economically challenged, isolated cities and towns around the state.

“I don’t think we really know what is going on,” said Claudia Jimenez, a political activist in Richmond, who said that roughly half of the city’s residents live in rentals, and more than 60% are African American or Latino — two groups that have elsewhere have suffered disproportionately from the pandemic.

Gov. Gavin Newsom for several days has vowed to increase coronavirus testing and medical care in 86 “testing deserts” statewide, places that have little access to health services. As of Thursday, his office had not released names of communities that would get the testing, the quantity of testing and how quickly tests would be offered.

Contra Costa County officials said Thursday that they were taking steps to expand four new testing sites, including one in San Pablo, next door to Richmond. But county officials said they haven’t heard any news about state testing in Richmond or elsewhere.

Richmond and West Contra Costa were dealt a blow in 2016, when the region’s only hospital, Doctors Medical Center, closed. That spawned fears that health conditions would deteriorate and make the population even more vulnerable to diseases, including viral infections.

There is a Kaiser center in Richmond that offers emergency services. The closest trauma center is in Walnut Creek, a 25-mile drive that winds through congested Oakland.

Since the Bay Area announced its first confirmed coronavirus case on Jan. 31, there were concerns that communities such as West Contra Costa would be hit hard. So far, Richmond seems to be holding.

As of Friday, the city accounted for just 83 of Contra Costa’s 763 positively identified cases. As of April 25, there have been at least 25 deaths in the county. The numbers on layoffs, as well as missed rent and mortgage payments, are also unclear.

A drive-through tour of the city on Wednesday and Thursday indicated many shops were closed, and like elsewhere in the nation, the streets appeared relatively empty. People seemed to be indoors, or outside on their lawns, tending to their gardens, or in their driveways working on their cars.

On Wednesday morning, scores of cars were lined up along the west side of 23rd Street, slowly inching south toward the Richmond High School entryway.

They were in line to receive bags of food — containing produce, prepackaged meals and milk — from school officials and volunteers.

The West Contra Costa Unified School District is providing three meals a day to every person under 18 — regardless of school attendance.

Since the shelter-in-place rules began in the Bay Area on March 16, more than 500,000 meals have been handed out, said Barbara Jellison, food coordinator for the district.

“We’ve been pretty busy,” Jellison said.

Seventy-two percent of the kids in the district — which includes 54 schools across five cities — qualify for free lunch; 92% at the high school.

According to Richmond High’s principal, Jose De Leon, of the 1,500 children that attend his school, roughly 400 have been there for less than two years.

Statistics from New York to California show that African Americans and Latinos are more likely to die from the disease than whites or Asians. They are also more likely to contract it, largely because they are over-represented in high-risk industries, such as support staff in nursing homes, postal work and restaurant service. Many are unable to shelter in place at home.

“The alarming COVID-19 mortality rate in America’s communities of color can be directly attributed to problems with health access and resources,” said Tracey Brown, chief executive of the American Diabetes Assn., in a statement. “Those with the fewest resources are the least likely to have access to quality health care, and COVID-19 testing is no exception.”

A new report from the Commonwealth Fund, a nonpartisan public policy foundation, found that in communities with high densities of black residents, both coronavirus case counts and deaths were higher than in communities with fewer.

Coronavirus Journal

Two Times journalists are embarking on a journey throughout California to cover the nation’s most populous and diverse state during the coronavirus crisis.

For instance, while only a third of the U.S. population lives in 681 counties classified as having a high concentration of black residents, more than half of all COVID-19 cases and more than 60% of deaths occurred in those counties.

“The results are stunning,” said Laurie Zephyrin, an expert in vulnerable populations with the Commonwealth Fund. “What we are seeing unfold in front of us is really a compounding of already existing disparities that are heightened when you add a pandemic to the mix.”

Jimenez, who was working from home on Wednesday morning, said she was concerned about her city.

As her two children, Antonio, 11, and Alicia, 6, worked on their school lessons in her living room, and her husband, Eli Moore, fielded work calls from their bedroom, she noted the demographics that make the city susceptible: a high percent of the population below the poverty level, around 15% — and that was before the pandemic — and a large number of foreign-born residents, roughly 35%.

She also brought up the recent drop in oil prices.

Although she’s been concerned for years about the air quality in Richmond, which sits right next to a Chevron refinery, she recognizes the oil company is a major employer in the city.

And with the industry so battered right now , she suspects the city’s major employer is going to start laying people off.

“Chevron’s U.S. refineries are currently making adjustments to their operational plans to match their production with the lower market demand,” said Sean Comey, a Chevron spokesman, when asked about the refinery’s status and production output.

And while Chevron is the largest employer, other businesses in Richmond — many of which are minority owned — are suffering, too, said Jimenez.

At Rich City Rides, on MacDonald Avenue, owner Najari Smith said he’s had to reduce hours, and the shop is now closed two days a week.

In recent days, however, he said things have started to tick up.

“I think people are riding their bikes more,” he said. “If it’s a choice between sitting in a bus with lots of other people, or riding alone on your bike, people are choosing to ride.”

But for Miguel Garcia, finding enough money to make his rent is major concern.

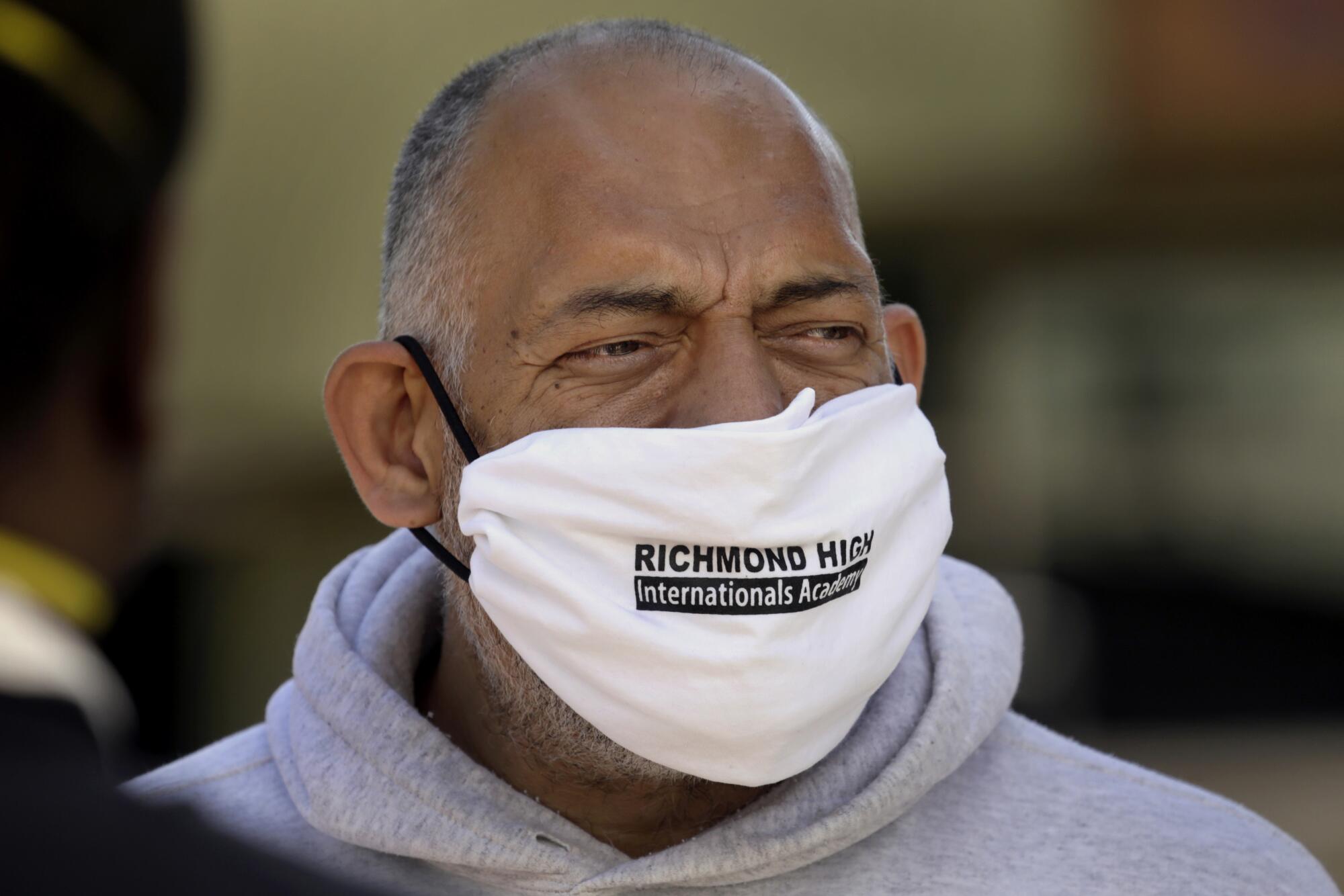

On Thursday, Garcia was standing in the parking lot at the Home Depot in El Cerrito, on the border of Richmond.

He was one of dozens of day laborers in the lot, looking for work in landscaping, painting or minor construction. He said that before the pandemic, he’d usually get work three or four days a week, at a rate of $15 an hour.

But now, “there’s nothing,” he said, speaking through a red bandanna tied around his face. “People are afraid to have us in their home.”

He lives in an apartment in Richmond with his son, daughter and 5-year-old granddaughter. And while his family was able to make the rent on April 1, he’s not sure they’ll have the $2,100 they need for May.

On Tuesday night, two city councilmen introduced an item onto the council meeting agenda that would have suspended all rent and mortgage payments for the duration of the shelter-in-place orders. It was voted down. However, an emergency order from March 17, which prohibits all evictions during this time, still stands.

Garcia, who came here 14 years ago from Guatemala, said if things get worse, he may have to go back. “I can’t believe I’m saying this, but things may be better there.”

When he heard about the food service offered by the schools, he brightened, and called his daughter to let her know.

Times staff writer Anita Chabria contributed to this report.

Los Angeles Times reporter Susanne Rust and photographer Carolyn Cole are embarking on a road journey throughout California. They aim to give voice to those in remote parts of the state as they grapple with the worst health and economic calamity of our lifetimes.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.