Doorknobs, trash cans, gas pumps: Citizen scientists search for coronavirus on everyday surfaces

- Share via

SAN DIEGO — Keira McGee carefully drew a small square of cloth across the handle of the city trash can outside her home near San Diego State. She then dunked it quickly in a cleaning solution before tucking it away inside a small test tube filled with a pink liquid. Snapping the lid closed, she slipped the vessel inside a red-and-white cooler alongside 15 other identical specimen tubes.

McGee is one of the first to sign up for a new research effort that seeks to learn more about how the novel coronavirus spreads and mutates on common surfaces by enlisting an army of citizen scientists to collect nearly 10,000 samples from throughout the community.

It was a new experience for someone whose day job entails making costumes for La Jolla Playhouse. But when she spotted a post online from local doctoral candidate Jason Baer seeking volunteers, she said helping a team of researchers at San Diego State track the invisible threat that has shut down so much of the world had a certain appeal.

The idea that swiping shared surfaces, from doorknobs to gas pump handles, might help scientists learn how to better contain the threat was too powerful to pass up.

“It’s empowering that somebody working in theater is able to contribute a tiny bit to this process; it feels really good,” McGee said.

Researchers are using artificial intelligence programs to navigate the coronavirus crisis. AI helps them decide which patients are most at risk.

Baer and fellow doctoral student Mark Little have recently worked to design the core methods that now allow the university to put out a call countywide for a total of 1,000 people to help collect samples from surfaces throughout the region, sending them back to university labs for molecular analysis by microbiologist Maria-Isabel Rojas. The effort is overseen by viral ecologist Forest Rohwer and mathematician Naveen Vaidya and is funded by a rapid-response research grant from the National Science Foundation.

The team has already collected about 700 samples in the community to make sure the process that McGee used last week works. The amount of coronavirus circulating on surfaces, Rohwer said, is expected to pick up as the strict set of social-distancing measures are gradually lessened, making the period between now and roughly mid-June prime corona hunting season.

“Now, the density is going to go up, so this is a very good time to be collecting,” Rohwer said.

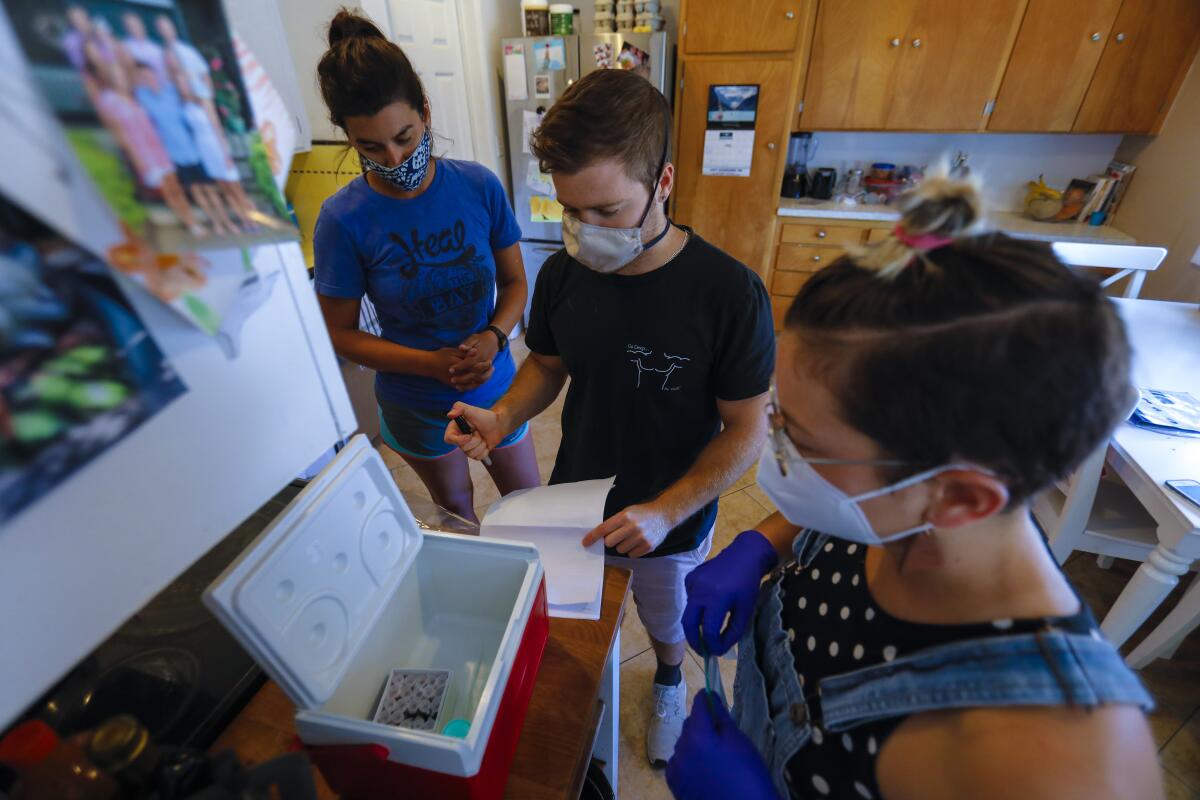

The team will select participants from submitted applications based on where they live and a few other factors, and will provide each with 16 vials, gloves, masks and swabs made from squares of floor-sweeping pads. Participants are free to decide where to collect their samples, staying close to home if they want or venturing further out. The work should be carried out over a two-week period and samples must be kept cold once they’re collected to keep viral genetic material from degrading.

It is key that participants aren’t all clumped together in one area. Sampling as broad a range of locations as possible will help researchers understand better which areas are more prone to have more virus present and which have less activity, helping paint a picture of how the virus moves through the real world.

It is clearly the case that small water droplets that spray into the air when an infected person sneezes or coughs play a significant role in transmitting the coronavirus from one person to another. It’s also clear that viruses left on surfaces, most significantly when an infected person wipes their nose or mouth and then touches an object that is then touched by another, is another route for the virus to find new hosts.

But there is still more to learn about the relative risk involved. For one thing, most of the studies that have looked at how long this pathogen can survive on surfaces have been conducted under controlled laboratory conditions. But there’s nothing controlled about the real world where infections actually occur.

The new coronavirus can live in the air for several hours and on some surfaces for as long as two to three days, scientific tests have found.

“Really, how much of the spread is actually related to surfaces is still a really big question,” Rohwer said.

The pink chemical inside the 16 test tubes that each participant receives contains TRIzol, a chemical that isolates and stabilizes the ribonucleic acid chains that store viral genetic codes. A first step exposes the whole sample to a chemical that is essentially dish soap, killing any microbes that were alive at the moment they were picked up. Making sure that nothing is still growing creates a kind of snapshot of that particular moment in time.

From there, genetic analysis works a little like carbon dating, examining the condition of the genetic code inside viruses to see how much it had already deteriorated at the moment the sample was taken. The more degradation detected, the longer the virus was probably present on a surface. In locations where the novel coronavirus turns up in samples, a research team will follow up with additional focused testing to corroborate initial findings.

Understanding where and when viruses are present is just the right kind of food for Vaidya’s mathematical models. Modeling will combine viral data with many other types of information, everything from temperature and time of day to demographic and socioeconomic information. Analyzing all of those factors in relation to each other should help tease out better information on where novel coronavirus is most and least dangerous in the environment.

Ideally, modeling might shed new light on whether, say, gas pump handles or elevator buttons have a higher probability of transmitting the virus from one person to another. Once scientists know more about the riskiest situations, public health policy could tighten its focus, coming up with higher-precision methods to lessen that risk.

“We can actually quantify what is the risk of getting infected through the environment,” Vaidya said. “If we know the risk of the environment, then we can develop the dynamics model, at a population level, of how this virus is spread including both direct transmission and environmental transmission.”

The researchers at San Diego State are collaborating with a similar program underway at UC San Diego called the Microsetta Initiative, a crowdsourcing endeavor that asks participants to contribute $99 for a kit to collect fecal, nasal, oral or skin swabs and mail them in for analysis. Though initially designed to gauge variation in the human microbiome — the vital and ever-variable communities of microorganisms that live inside our bodies — the program, co-created by Rob Knight, director of the university’s Center for Microbiome Innovation, announced in early April that it had expanded to collect data on the SARS-CoV-2 virus causing the current pandemic.

Other local efforts are underway in San Diego, Rohwer added, to study transmission through the air and for presence of the virus in sewage samples. Collaboration between various efforts, he said, should add up to something big.

“There is going to be a reasonably good overview of how the city has this virus,” Rohwer said.

Those interested in participating in the San Diego State environmental sampling project can apply by clicking the sign-up link at coralandphage.org, the joint lab website of Rohwer and fellow investigator Linda Wegley Kelly.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.