Sierra Club reflects on its racist roots and looks toward a new future

- Share via

As U.S. companies, politicians and institutions seek to atone for a history of systemic racism, the environmental movement is also grappling with a past built on white supremacy and a glaring lack of diversity in its current rank and file.

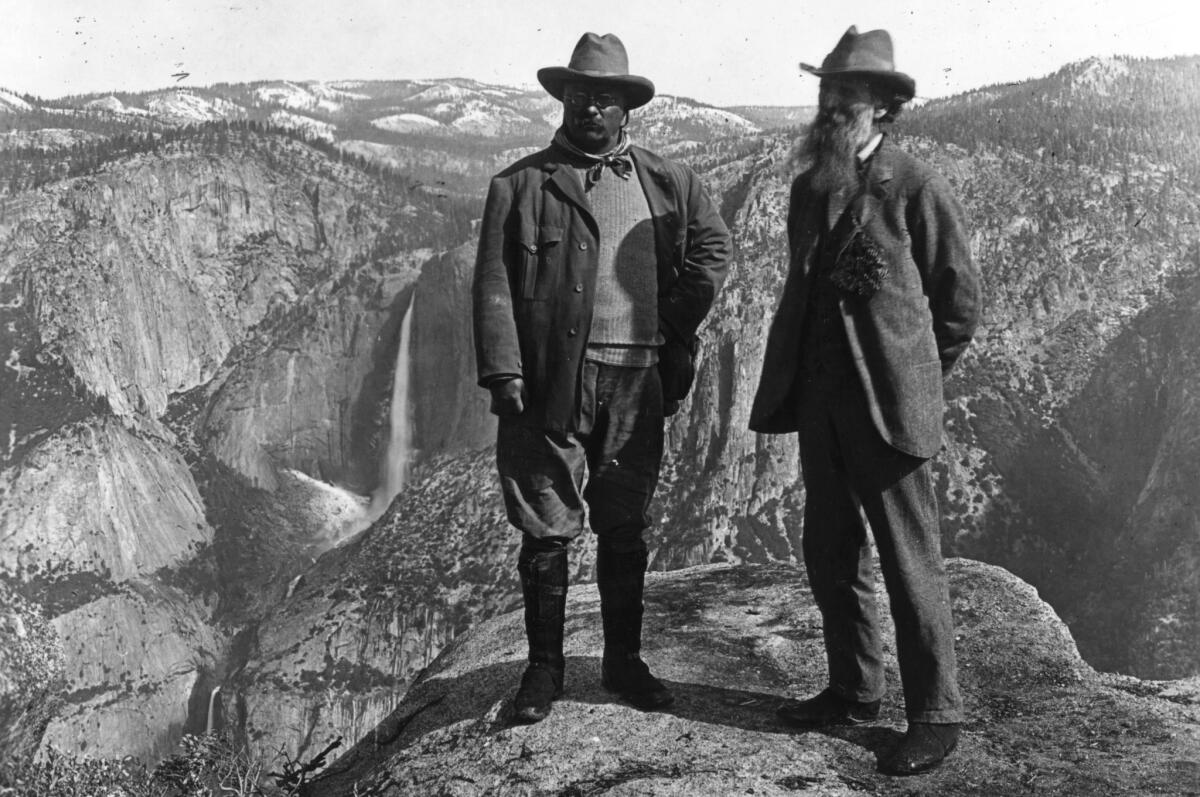

On Wednesday morning, Sierra Club’s executive director, Michael Brune, penned a missive on the organization’s problematic history — from founder John Muir’s racist statements about Black and Indigenous people, to its affiliation with the eugenics movement, and its current, predominantly white membership and sentimentality.

”... willful ignorance is what allows some people to shut their eyes to the reality that the wild places we love are also the ancestral homelands of Native peoples, forced off their lands in the decades or centuries before they became national parks,” he wrote. It is this ignorance, he said, that “allows them to overlook, too, the fact that only people insulated from systemic racism and brutality can afford to focus solely on preserving wilderness.”

As advocates for a more equitable nation take down Confederate statues in the South and those of Christopher Columbus and Father Junipero Serra in California, Brune called for the organization to reexamine its own role in perpetuating white supremacy, “starting with some truth-telling about the Sierra Club’s early history.”

Muir’s legacy — the father of the national park system, whose words shaped the way generations have thought about the wilderness and how it should be protected and managed — has come under increased scrutiny in recent years. Many questioned whether his ethos is still relevant in today’s world.

This history has come into even sharper focus since the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis as a renewed social awareness of systemic racism takes hold.

“The first step is to own mistakes personally and institutionally,” Brune said in an interview. “There were early leaders in our organization who made harmful and disparaging remarks about Native Americans and Black people that haven’t been acknowledged by leadership in the organization for more than a century, so we’re owning that, apologizing for it.”

The club’s staff, membership and volunteers are predominantly white and the membership skews older.

“The Sierra Club is multi-generational and multi-racial but not nearly enough,” Brune said. “There’s a lot of work to be done in that regard.”

Many of the polluting industries that are propelling climate change disproportionately affect poor and non-white communities that live next to refineries and pipelines.

“It’s been an evolution over time,” said Kathryn Phillips, director of Sierra Club California. “Since the ‘90s, the Sierra Club has gotten more involved in California in urban issues and air pollution … What’s happening now is we are overtly recognizing that we have to make sure we are including all people.”

In 2004, the club was nearly dismantled after an internal rift grew between those who were advocating for tough immigration restrictions as a way to control environmental damage and those who felt such policies were inherently racist.

Marce Gutiérrez-Graudiņš of Azul, a group based in Oakland that aims to bring more Latino voices to coastal issues, said the Sierra Club’s reckoning with its history “was a long time coming, and it’s sadly a reflection of not just the Sierra Club but our field in general.”

Gutiérrez-Graudiņš has spent years framing issues from an environmental justice perspective but said until recently, it did not have the impact and reception it is now receiving — not just from decision makers but also from her conservation colleagues.

“We’re at a point where people can’t ignore it anymore,” she said. “There’s a confluence of all these changes that are coming together, and people are now taking action on this work that has been going on for decades.”

She pointed to generations of work by advocates such as Robert García, of the City Project, and others who fought for equitable access to clean air and water. Together, they pushed for California’s recent environmental justice law, which explicitly authorizes state officials to consider not only impacts to plants, animals and coastal habitats when making decisions but also the effects on underrepresented communities.

Gutiérrez-Graudiņš left the mainstream environmental movement almost a decade ago to amplify Latino voices and show there isn’t just one way to be a conservationist. For years, she has battled a misperception that Latinos don’t care about the environment and has urged colleagues in the environmental space to recognize how diversifying their meetings and events is not just about checking boxes.

“I was basically tokenized left and right, and I wanted to be able to say ‘no’ and do things the way I thought they should be done — informed by and led by my community,” she said. “There was this idea that there’s one way to do environmental work, that there’s one way to do conservation, that there’s one way to do outreach, and that if folks don’t show up to your thing, they don’t care.”

The Sierra Club has taken a number of steps in the right direction in recent months, she noted, including naming the first Latino in its 128-year history to lead its board of directors.

A recent poll, conducted by Yale and George Mason universities, shows that people of color are more concerned about climate change than white people.

The poll found that 49 percent of white people are concerned about climate change, compared to 57 percent of Black people and 69 percent of Latino people.

“There is definitely a reckoning underway, and it’s long overdue,” said Meera Subramanian, the Society of Environmental Journalists’ board president, who oversees a predominantly white membership-driven organization of environmental journalists. “The challenge now is to translate the promises made in an engaged moment into long-term action.”

“The environment isn’t polar bears and Yosemite National Park,” she said. “It’s the water in Flint, Michigan, and the air in New Delhi.”

Gladys Limón, executive director of the California Environmental Justice Alliance, said the Sierra Club and other major environmental organizations have traditionally wielded most of the power and benefited from the biggest budgets.

To advance their racial justice commitments, she said the major players need to make room for smaller, grassroots groups and shift philanthropic financial support directly to environmental justice organizations and communities.

Rene Henery, California science director for Trout Unlimited, noted that the environmental movement arose in a culture that was white and patriarchal: “Everything, from who could participate in that movement and have a voice to how the organizations came to be, to who was on the boards and how the organizations are structured” reflected that culture.

“It is what it is. Now we are trying to set a new boundary,” Henery said. “It’s in everybody’s interest to take care of everybody else because we’re all interconnected.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.