- Share via

As Dr. Louis Tran walked through the field hospital outside Arrowhead Regional Medical Center in Colton, he passed weary casualties of a COVID-19 surge with no peak yet in sight. Young and old, they slept on cots while receiving oxygen through nasal tubes.

One of the largest hospitals in San Bernardino County, the 456-bed facility ran out of intensive care unit space two weeks ago amid an onslaught of COVID cases across Southern California.

By now, the effects of the surge on hospitals have become familiar: Ambulances waiting up to six hours to offload patients. People suffering from other ailments, including one with kidney failure, getting treated outside the hospital for more than two hours before a bed opened up. Medical staff thinking about what other areas of the hospital, including conference rooms, can be used to treat the ill.

And yet, Tran said, he believes the worst is yet to come.

“We knew there was [another] wave coming in the wintertime,” Tran said. “But I did not expect to have as many sick people who required ICU care like we’ve been having.”

Hospitals across Southern California have been hit hard by the recent COVID-19 surge. Many of them are operating at peak capacity and are concerned about an even larger surge after Christmas and New Year’s gatherings. The feeling that the other shoe — a larger and heavier one — has yet to fall is pervasive among healthcare workers.

“We are short-staffed because there are not enough nurses to take care of all these patients,” said Vanessa Heaton, 34, a charge nurse. “I just don’t know, if it gets any worse, how we’re going to be able to handle it.

“We hope that it slows down at some point, but we’re kind of scared of post-Christmas,” she added.

Heaton worries that if the hospital becomes too inundated with COVID-19 patients, it will be harder to care for people having other emergencies, including victims of crimes.

“People are still going out, they’re still getting shot or stabbed, and our hospital has to deal with all that on top of COVID,” she said.

If ever a region was susceptible to faring poorly during a pandemic, it is one like the Inland Empire, with rampant poverty and high rates of people with just the kind of underlying health issues that COVID-19 preys on. And San Bernardino County has been more resistant to state mandates than L.A., with officials clashing with Gov. Gavin Newsom over the latest stay-at-home order.

For weeks, coronavirus cases in this region were growing faster per capita than in most counties in the state, according to a Los Angeles Times tracker.

Although the infection rate has slowed a bit in San Bernardino County, it is still listed as one of the 10 counties hit hardest by the recent COVID-19 surge.

Over the last seven days, there were about 744.4 cases for every 100,000 residents in San Bernardino County.

The situation is far worse in Riverside County, where in the last seven days there were 941.7 cases per 100,000 residents.

A Times analysis of coronavirus case rates in communities for which data are available found that, of the top 50, about half were in the Inland Empire, including Riverside, San Bernardino, Perris, Moreno Valley, Jurupa Valley, Bloomington, Barstow, Colton, Rialto, Victorville, Fontana, Highland, Adelanto and Hesperia.

Kareem Gongora, a board member of the Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice, was not surprised.

“Those are all minority communities,” he said. “They’re predominantly Latino, Black and low-income.”

He said many people here work at warehouses and live in multigenerational homes under crowded conditions. The region is home to a booming logistics industry that has created tens of thousands of warehouse jobs.

But that same industry has also helped drive up air pollution, which has led to an increase in asthma rates, Gongora said.

“We call this region the diesel dead zone because your increased exposure to particle matter worsens Alzheimer’s disease, heart disease and a slew of other diseases,” he said.

At Arrowhead Regional Medical Center, a short walk from the medical tent, men were putting the final touches on trailers that will add about a dozen treatment rooms for COVID-19 patients. Twelve more rooms will be added in the coming days, officials said.

Ravneet Mann, a clinical director at Arrowhead, said they have been trying to plan for the worse. She said they have placed cots in conference rooms should they run out of space again.

“If worse comes to worst with our planning, then we’ll use the cafeteria,” she said. “We can go to the lobby also.”

On the second floor, a surgical intensive care unit was converted to a COVID-19 unit during the summer. At least 32 patients lay in beds; most of the men and women were intubated.

Mann said that if the situation becomes more critical, nurses may have to consider taking on more patients. Normally the ratio is one nurse for every two patients. Hospital officials say staff shortages have led them to alter those ratios at times.

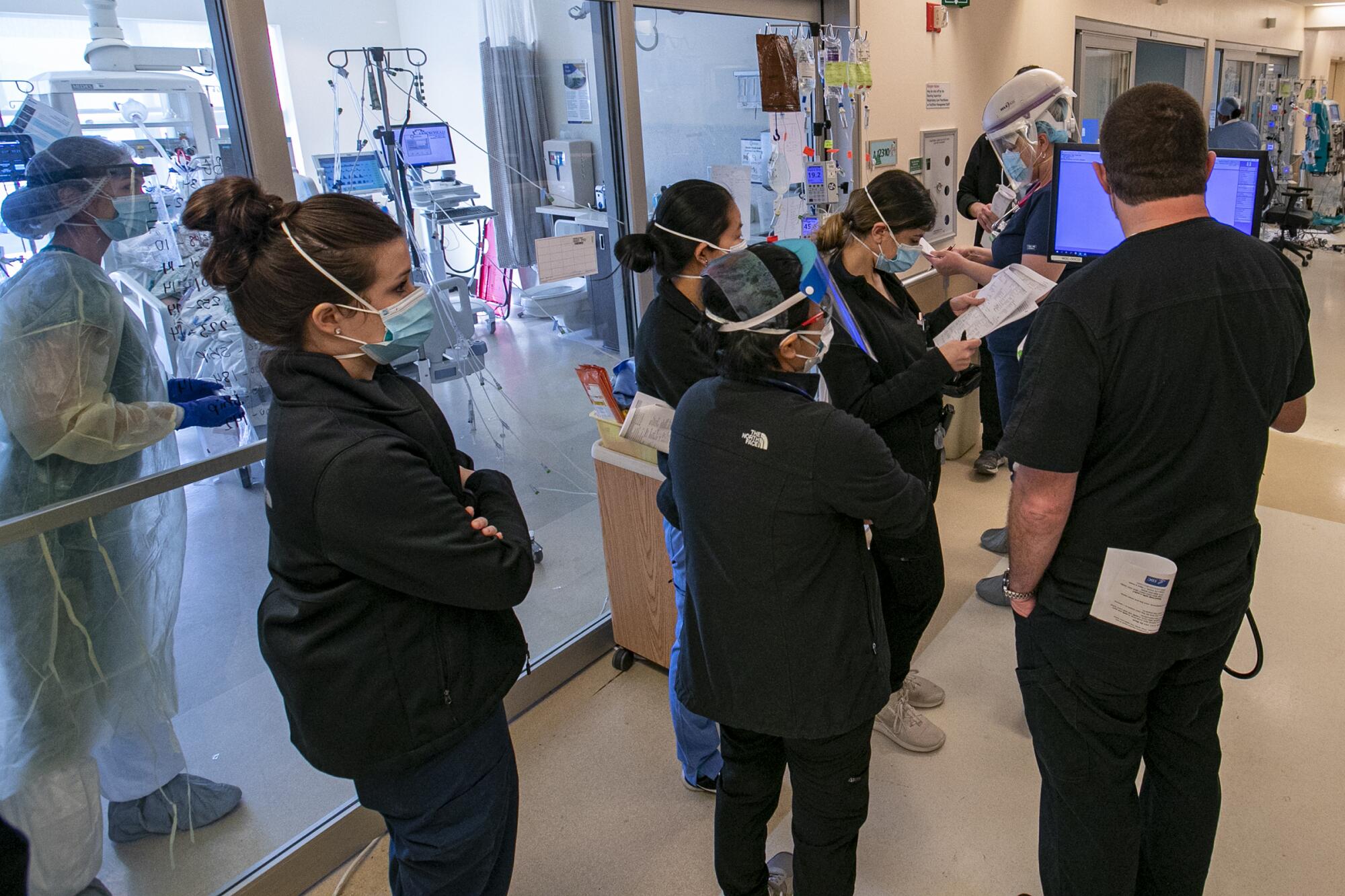

But it takes a lot of work to care for even one COVID-19 patient who’s been intubated. Nurses not only must monitor IV pumps but sometimes also have to flip patients onto their stomachs because it helps them breathe more easily. It takes about six nurses to flip a patient.

Around the corner, a 41-year-old man lay intubated. He arrived Dec. 12, and four days later his condition worsened. He recently was placed on dialysis after his kidneys began to fail, another complication brought on by the disease.

“That’s our average age that we’re getting,” Mann said. “They’re coming in younger and coming in sicker.”

On average, patients are going into respiratory and cardiac arrest at least four times a day. The medical staff has saved people from dying during those medical emergencies.

But every day, at least two people are dying of COVID-19 here.

“That’s the hardest thing,” Mann said. “We became nurses to make sure patients get better. To see a death every single day is just so depressing.”

The hospital staff has shown resiliency during the latest surge, which has become the deadliest since the pandemic started.

So far, more than 26,000 people have died of COVID-19 in California. It is the third-leading cause of death in the state.

During moments of relative calm, nurses share tips about caring for patients. They discuss scheduling shifts. There are random conversations and laughs. And always, there is praise for the exceptional care they provide to patients.

“There are some pretty amazing nurses here,” Mann said.

In the medical ICU on the fourth floor, Elizabeth Koelliker, 36, the charge nurse, dashed from one patient to another, checking IV pumps.

“There’s just way too many patients and not enough nurses and we’re trying our best,” she said. “You think last week was bad, and then you come in this week and it’s worse.”

Koelliker arrived at 7 a.m. and had been unable to take a break for more than six hours because there was no one to take her place.

The state has sent 24 ICU nurses to the hospital. Although workers say it helps, it’s still not enough.

In the last few days, Koelliker said, some nurses have had to come in for some overtime just to help relieve other nurses for lunch.

“We would not be able to do what we’re doing without the teamwork we have here,” she said.

More help is expected to arrive soon as 75 Air Force and Army doctors, nurses and other medical personnel have been deployed to California hospitals, including Arrowhead Regional Medical Center, according to Army officials. Mann said the hospital will get 14 nurses, four physicians and two respiratory therapists.

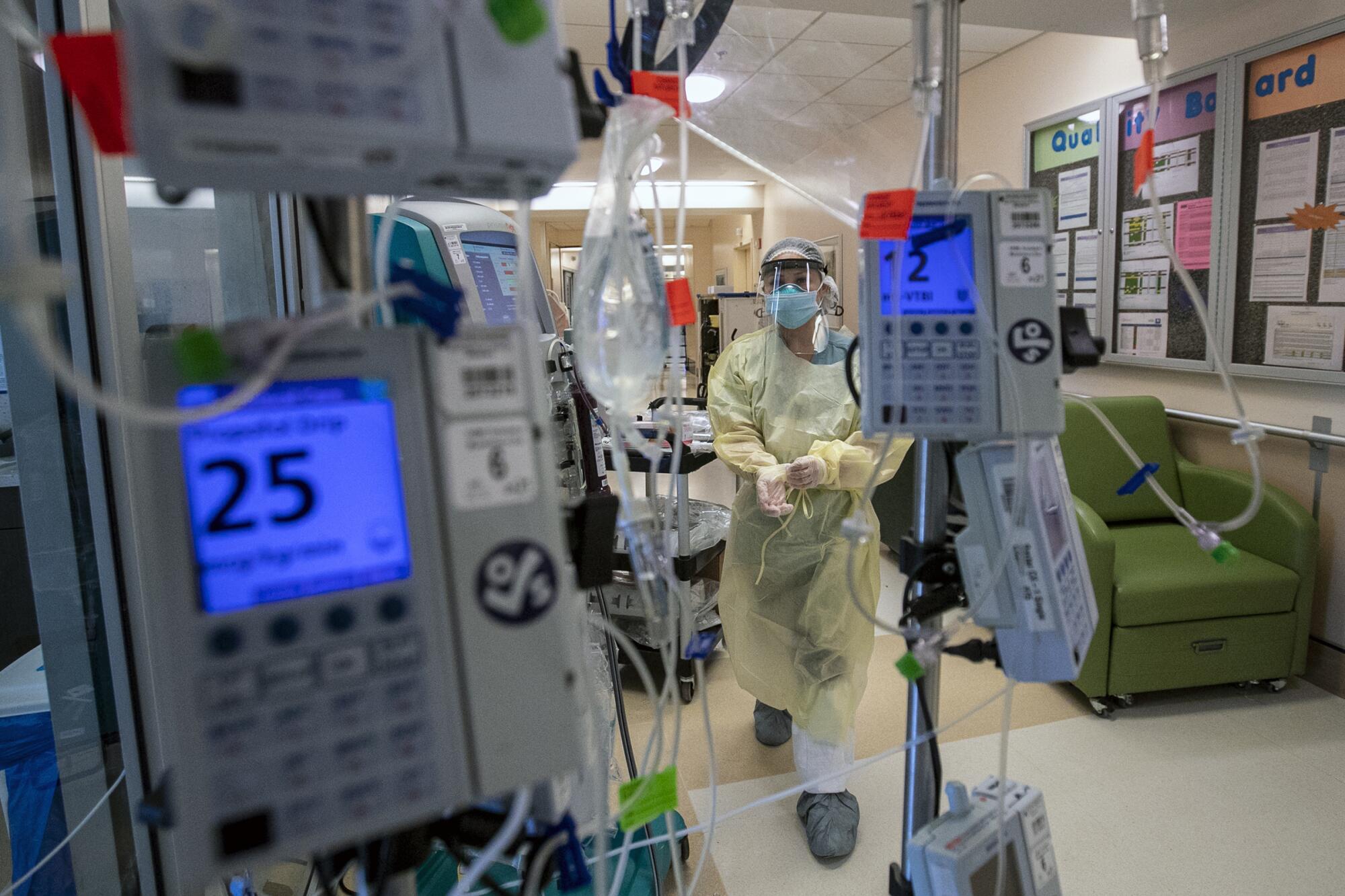

It was just about noon when a nurse put on a negative-pressure helmet and a yellow plastic gown over his scrubs before sliding the glass door open and walking into a patient’s room. Outside, a second nurse held several IV drips that he passed through a gap on the side of the door. The nurse inside grabbed the plastic tubes, gave a thumbs up and walked over to the patient.

To limit exposure to COVID-19 patients, the staff has placed all the medication pumps outside the patient rooms. If healthcare workers go into a patient’s room, it’s often one nurse at a time. Mann said she is trying to obtain more negative-pressure helmets for her nurses.

“If I can keep them safe,” she said, “they can keep taking care of patients longer.”

Koelliker said it took a while for nurses to get used to not walking into a patient’s room without putting on the proper gear.

“We’re not used to not getting to a patient when they need us, so a lot of us found ourselves running in,” she said.

Koelliker said she worries about what lies ahead. She’s afraid that nurses will be overwhelmed by the number of patients they will have to care for — even with the extra help that’s coming. She thinks about the phone calls she’s had with family members who blame themselves for playing a role in the relative’s condition. She worries about her colleagues.

“I’m extremely scared,” she said. “It’s already bad now.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.