In the pandemic, businesses and nonprofits become authors

- Share via

The menu was always small at Sonoratown on the outskirts of the Fashion District, and the coronavirus didn’t change that.

The critically acclaimed Mexican restaurant still sells tacos and burritos filled with mesquite-grilled beef and chicken, flaky handmade flour tortillas and an awesome coconut horchata that’s like an island vacation in a cup.

But the small spot looked like a mini-mart when I visited last week for the first time in more than a year.

Cases of beer and Mexican Coke rested on bars where eaters used to lean. Boxes of tortilla chips covered up art on the brightly colored walls. A counter with random knickknacks blocked anyone from entering what used to be the dining room and patio.

Sonoratown needed to diversify to beat back the financial devastation wrought by the pandemic and is doing a good job, co-owner Jennifer Feltham told me as she showed off the restaurant’s latest offering: a book.

The 93-page self-titled effort isn’t your typical restaurant tome chockablock with studio portraits on shiny pages.

There are a couple of recipes, but the focus is on the life stories of Feltham and her business and romantic partner, Teodoro Diaz-Rodriguez Jr. It’s a quick, enjoyable read that pairs well with Sonoratown’s salsa roja and is part of a recent trend born of desperation and pride.

Multiple Southern California businesses have published books about themselves to try and tap another revenue source in the wake of a disastrous year.

The inspiration to become authors isn’t purely financial: COVID-19’s existential disruption of life convinced these new Twains that 2021 was the perfect time to share their stories with the world.

Because if not now, when?

That’s how Feltham felt when an Australian book publisher asked her and Diaz-Rodriguez to pen the latest entry in its “Take Away Los Angeles” series. The collection highlights restaurants in the city and lets them keep 50% of all sales — an unheard-of take in an industry where writers rarely see any residuals.

“I’m not a writer, so I didn’t have the time to say no when they asked,” said Feltham as we sat in her office, which used to be Sonoratown’s main seating area. “I was worried people would think it’s navel gazing or indulgent, but people were looking to support.”

Feltham, whose restaurant has been featured in this paper and in Netflix specials, also enjoyed the challenge of doing something beyond the usual T-shirts or bumper stickers that businesses have long peddled to make some extra dough — or, in Sonoratown’s case, masa.

“I feel weird with people walking around with our name on their chest,” she said. “But this is a good way for you to do work and not feel like you’re just accepting money from people who pity you. It’s nice to allow people into something deeper in this Instagram-y world instead of a pithy quote next to a picture of a taco.”

The situation was different for CIELO, which is dedicated to helping Indigenous communities from Mexico and Central America in Los Angeles. The nonprofit created a fund that has doled out $1.7 million to families and individuals who are in the country illegally — to help with food, rent and other expenses.

That drive was important, said CIELO Executive Director Odilia Romero, but she also saw a different need.

“People started to die more, and stories were getting lost,” said the 50-year-old, who is Zapotec. “We needed to act now.”

Romero had long wanted to do a book about the history of Mexican and Central American Indigenous communities in Southern California. She gathered a group of women over a week of get-togethers at CIELO’s office and her backyard to talk about their lives over food and mezcal.

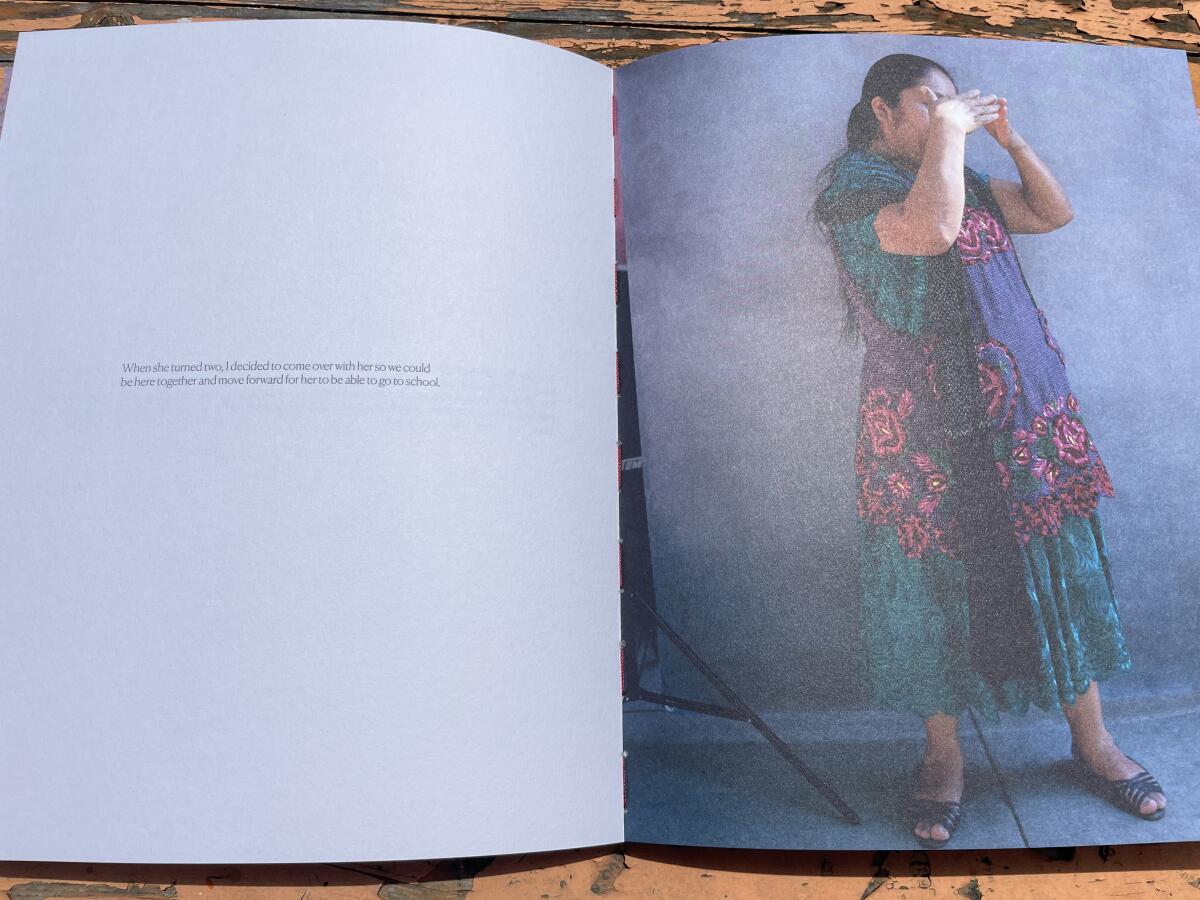

The book “Diža’ No’ole” (“Women’s Word” in Zapotec) is hauntingly beautiful, and all proceeds go to the women who participated. Poems are offered in Indigenous languages without translation. Photos switch between vibrant colors and muted black-and-white as caption-length histories go from the subject’s favorite dances and dishes to the struggles they face.

“Before, the fear was deportation, and now, for many of us, the fear is getting infected, especially if we don’t have family around,” one woman said. “Who would take care of us ... in those moments if we get infected?”

The book ends with a list of the participants’ hometowns. All the women wear the distinct textiles of their hometowns, not to exoticize themselves but as a statement of pride in a world where they face discrimination from English and Spanish speakers alike.

“You love being Indigenous in your hometown association event, but you don’t want to put that out there,” said CIELO Vice Executive Director Janet Martinez, Romero’s daughter. “We need to be out there and show we are here and resilient in L.A. County.”

“The book is literally a physical space that Indigenous people can occupy,” added Romero. “COVID made it happen.”

If “Diža’ No’ole” is a document of where we are now, “Alex’s Bar” is a riotous celebration of what once was and hopefully can be again.

It’s a collection of concert shots from the legendary Long Beach music venue, and the cover photo says it all: a packed, sweaty slam pit where people merrily crowd-surf and social distancing is something for squares.

Photographer John Mairs thought of the idea late last year when he saw the travails of Alex’s Bar play out on Facebook.

“One day, I saw them [post] a photo of this big tent outside,” said the San Clemente resident. “The next morning, they posted that winds had torn it down, and a photo of that. It was like, ‘Man, this poor guy.’”

Mairs asked his contemporaries in the concert photography scene — most of whom hadn’t worked in a year — to pick some of their best shots for a coffee-table book, with all profits going to Alex’s Bar. “People are still struggling to make ends meet, but everybody really wanted to help one way or another,” he said.

He was fearful it would be a lot of work for a pittance. “I didn’t want to go through all this and hand [bar owner] Alex Hernandez 10 bucks.”

So far, they’ve raised more than $6,000.

“It’s bands that everyone loves,” Mairs said. “It’s great photography that a bunch of people haven’t really seen. It’s also supporting a venue and an owner that everybody loves.”

Buy all of these books, because the groups involved are Southern California icons in their respective scenes. Learn about the unsung legends in your backyard. And if you’re a struggling business or nonprofit, write your own. Consider Feltham’s closing words.

“I’ve had my story told so many times by others,” she said. “But this is our story told 100% our way. Claim your narrative — it makes you feel powerful.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.