- Share via

Just down the street from Pamela and Valentin Marquez’s tidy two-bedroom home, next to an industrial strip where trains rumble through the night, is a park and playground with a walking path through oak trees.

For decades, the couple, now in their 70s, took on issue after issue in El Sereno, beating back plans to build a freeway offramp nearby, advocating for improvements in their working-class neighborhood — and building the El Sereno Arroyo Playground.

In their nook of Los Angeles, they are the type of hyperengaged citizens that turn a community’s needs into political action. But leaked audio of three council members using racists insults as they plotted to reshape district maps has upended City Hall and thrown into question how much neighborhood advocates can do in a district that’s in limbo.

Councilmember Kevin de León, the once powerful pro tempore of the California Senate who ran for mayor in the primary election this year, refuses to step down despite deafening calls to resign, saying he won’t leave his constituents without representation.

Once considered a trailblazer, De León has been politically isolated by the scandal, and his council colleagues are moving to cut off the little power he has remaining in the two years left of his term.

Although a move to recall him is already afoot, it could take months to qualify, if it does at all.

“It’s frustrating to be in the dark waiting on the political game to play itself out,” said Pamela Marquez, who founded Concerned Neighbors of El Sereno with her husband. “The communities in Council District 14 are so disenfranchised right now by everyone.”

About a quarter-million people, the majority of them Latino, live in this district hugging the eastern edges of Los Angeles that stretches from downtown and the old Mexican American barrios of Boyle Heights to the gentrifying neighborhoods of Highland Park and Eagle Rock. The district has played a critical role in city governance as the beating heart of Latino politics, and as the hub of the iconic Eastside culture with landmarks like Mariachi Plaza and the new 6th Street Viaduct.

There are pressing issues for its council member to deal with: the continued cleanup of neighborhoods around the Exide battery recycling facility, looming evictions of residents at abandoned homes owned by the California Department of Transportation, homeless camps, park funding and city-backed food drives that residents rely on during the holiday season. The district includes some of the poorest parts of the city and has a large immigrant population and high rates of renters.

“I’m extremely disappointed and sad for our community,” Marquez said.

In the leaked audio recording released last month, De León conferred with Council President Nury Martinez, Councilmember Gil Cedillo and Los Angeles County Federation of Labor President Ron Herrera about keeping districts in Latino control, making racial insults and not objecting when Martinez made even cruder ones.

He accused fellow Councilmember Mike Bonin of using his Black son as an accessory like Martinez holds a Louis Vuitton bag. And he compared Black political power in Los Angeles to the Wizard of Oz.

“When you’re at the side of the curtain, it’s like this big voice, it sounds big,” De León was captured saying. “It sounds like there’s thousands. And then, when you actually pull the curtain, is that you see the little Wizard of Oz. You know what? It’s the same thing.”

Martinez and Herrera resigned after news of the tape broke. Although Cedillo joined De León in refusing to do the same, his term ends next month.

The tape showed a raw side of De León, who was raised in poverty in San Diego by a single mother, a Guatemalan immigrant who cleaned homes to support him. Race and class shaped his worldview. In the recordings he complains of a double standard judging Latino politicians, saying the media criticized him for a lavish inauguration in 2014 while white colleagues who had similar events received little scrutiny.

He said the biggest threat to Latinos was not “those crazies in Orange County who are pro-Trump.

“It’s the white liberals. It’s the L.A. Times.”

The racist comments on a recording that rocked Los Angeles City Hall ensnared Councilman Kevin de León in controversy. The tape also revealed an undercurrent of ambition and grievance in his political career.

In the first days after the leak, raucous protesters nearly shut down council meetings and De León’s district offices were shuttered by staff out of safety concerns. De León has gotten multiple death threats. Protesters set up tents outside his Eagle Rock home with signs that read, “just 25 Black people yelling.” The City Council censured De León and Cedillo and stripped them of their ability to sit on or chair committees, where projects largely get decided and much of the council work gets done. Members are also conferring over how to limit De León’s ability to make motions, approve contracts and access the discretionary funds given to each council office for projects like holiday giveaways or movies at the park.

In television appearances shortly after the tape emerged, he apologized and said he doesn’t want to leave his constituents without representation, telling Noticiero Univision anchor León Krauze, “I am extremely sorry, and that is why I apologize to all my people, to my entire community, for the damage caused by the painful words that were carried out that day last year.”

But the protests continued and De León has still not attended a City Council meeting. He said he and his staff have been carrying on business attending food giveaways, celebrating veterans or other milestones, and he has slowly emerged in public, if not at City Hall. Earlier this month he toured skid row, where he helped secure a $47-million grant for street lighting, crosswalks and tree planting.

“I still have a vote that impacts the lives of those who elected me,” De León said in an interview. “In a democracy, only the voters can give that and take that away.”

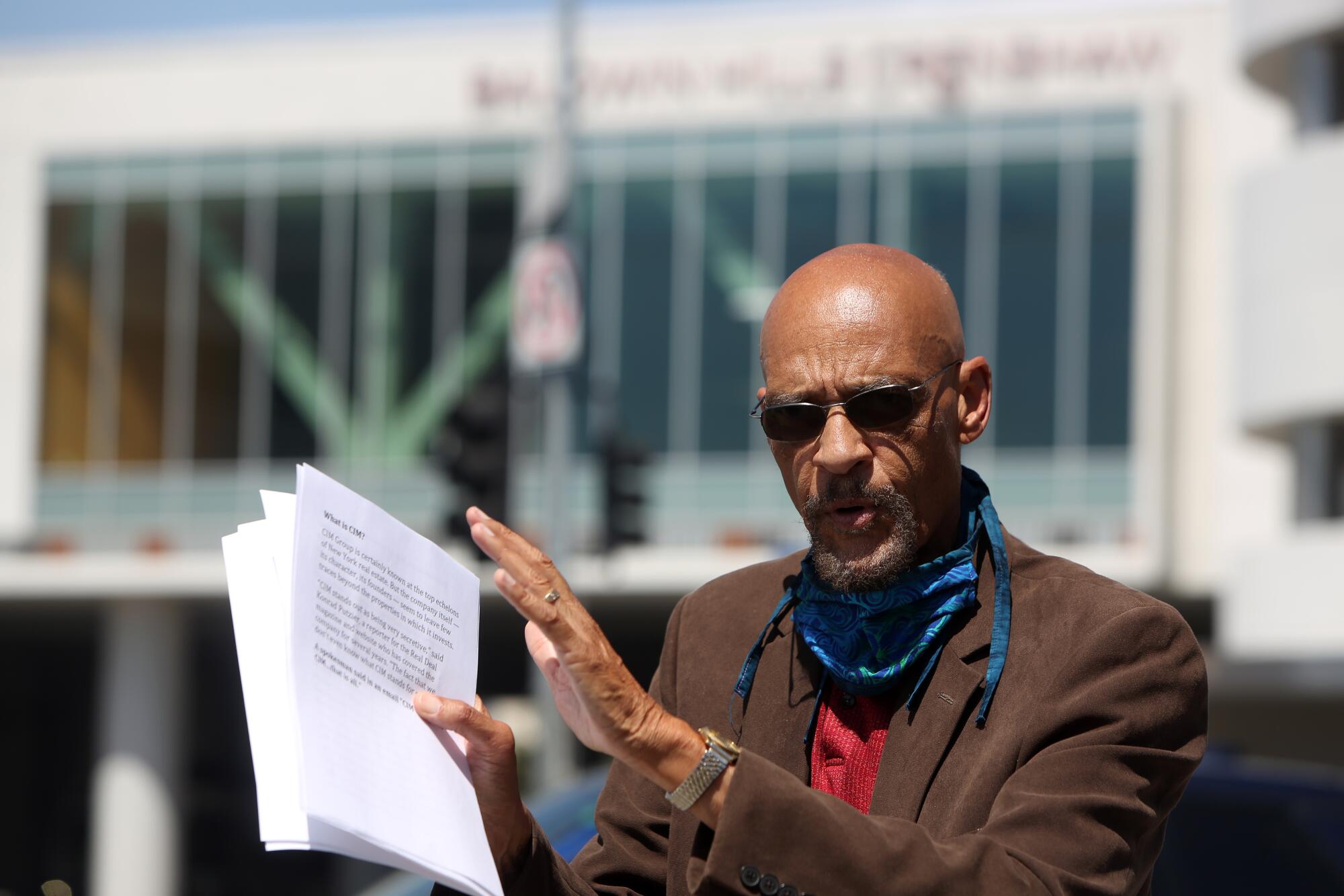

He has been trying to meet with leaders of the Black community, such as Los Angeles Urban Policy Roundtable President Earl Ofari Hutchinson.

Hutchinson, who met with him for about an hour, said De León agreed to reach out to those who would listen and share with them his record in Sacramento, where he named the first Black sergeants-at-arms to the state Senate and allied with Black political leaders.

“From what I’ve seen, he has a fairly good record when it comes to working with African Americans,” Hutchinson said. “I haven’t seen any indication ... that Kevin de León was out to sabotage us.”

Hutchinson was among the first to call for his resignation and, although his mind wasn’t changed, he said De León must now work to prove himself going forward.

“I told Kevin, ‘You know you got a tiger by the tail here. You got a firestorm. And you know, it’s not gonna go away.’”

He thinks De León needs to create policies that ensure racial equity and hold a town hall to air grievances about the tape.

De León says he is doing work for his constituents that a novice legislator would not have the savvy or influence to do. Since becoming a council member, his office has secured $100 million in grants for the district. He built what was the nation’s largest tiny home village for those living on the street and authored legislation that increased the size of the illegal dumping pickup program.

“In spite of all the challenges, my staff and I are working hard as ever and leading on the most pressing issues in CD 14. We are working across the district, neighborhood by neighborhood,” he said. “It would be easier for me to walk away. But I love my constituents and my track record proves that I have always been about public service and delivering concrete results.

“I have led in the creation of parks, homeless and affordable housing, transportation infrastructure and drawn down more state funding than virtually any other district. In 2 ½ years I will have built six homeless housing sites; what other district has done that?”

The efforts to strip De León of any power enrage some of his constituents, who see them as no more than outside council members undermining their district.

“We didn’t vote these people in and yet they’re making decisions on our funding in the community,” said Sylvia Cruz, president of a neighborhood council representing El Sereno and the surrounding community. “Only the people that elected him can hire and only the people that elected him can fire him. ... That’s due process.”

A spokesman for City Council President Paul Krekorian, who co-authored the proposal to restrict De León’s power, said that he just wants oversight.

“Nobody is talking about canceling, withdrawing or reducing services that were previously scheduled,” said Hugh Esten. “The council is seeking oversight over any future reallocation of resources because [De León] has been censured and he may anticipate leaving office in the near future.”

Many in the district feel abandoned or just want him out.

“It’s a shame, it’s a shame,” said Msgr. John Moretta, the longtime pastor of Resurrection Catholic Church in Boyle Heights. “He is in absentia; we don’t have any representation. And that’s on his shoulders. That’s on his conscience.”

Council offices are the community’s voice, often advocating to fix buckled sidewalks or erect needed street signals. They can push to clean up trash or help to smooth out conflicts within agencies. De León said he thinks he can still do the work, as memories and emotions over the tape fade with time.

Some political experts agree. “Every day that he is there is good for him,” said longtime political consultant Rick Taylor. “People will forget. It just won’t be the most pressing issue anymore.”

Residents are weary, having been let down before. The council district is notorious for bald ambition and corruption.

For the record:

8:35 a.m. Nov. 20, 2022An earlier version of this article said Kevin de León ran for City Council in a special election to replace Councilmember Jose Huizar in 2020. It was not a special election.

Just two years ago, disgraced Councilmember Jose Huizar was suspended after being arrested and charged in a federal corruption probe. De León replaced him, but for months the district was without representation, endangering millions of dollars in funding.

Chinese developer of L.A. skyscraper convicted of bribing ex-L.A. City Councilman Jose Huizar. Wife, mother and brother of Huizar admit laundering cash payoffs.

Claudia Oliveira, president of the Downtown Los Angeles Neighborhood Council, said the group doesn’t want to find itself in a similar situation. Last time she looked to other council offices to introduce motions on behalf of the district residents, working with Councilmember Joe Buscaino to secure funding for extra security at a downtown pocket park.

Her group has largely cut ties with De León and has asked for him to resign. Worried that will leave the district without an advocate at City Hall, she is working to find empathetic council members who could help them tap funds or introduce motions.

“Now we are going through this again,” she said.

Before Huizar, who served the district for 15 years, some activists, such as Marquez, bemoaned his predecessor Antonio Villaraigosa, who they felt used the office as a pathway to become the city’s first Latino mayor before he served a single term.

The Boyle Heights area has been the key entry point for Latino political leaders for over 70 years. In 1949, Edward Roybal became the first Latino elected to the City Council since 1881, holding his seat for 13 years, before serving three decades in Congress. It wasn’t until 1985 that another Latino arrived, Richard Alatorre, a legendary dealmaker who became a powerhouse in city and state politics before leaving amid a federal corruption scandal. He reluctantly conceded that he had abused cocaine and later pleaded guilty to tax evasion, admitting that he had accepted $41,840 in 1996 from those trying to influence his votes.

“It’s so disappointing,” said Josefina Lopez, co-owner of Casa Fina in Boyle Heights, where politicians regularly hold fundraisers or make stops. “All these Latino men come in and then kind of make a difference and they get corrupted somehow.”

George Sanchez, a historian who has written on Boyle Heights, said there’s a pattern among the district’s politicians using the council seat as a means to line their pockets or as a launching pad to higher office.

Criticism of De León falls under the latter complaint. He has a reputation as a hard worker with sharp political instincts who has racked up legislative achievements and is unafraid of taking strong positions. But his ambition has bristled allies.

In 2018, he launched an unsuccessful campaign against Sen. Dianne Feinstein. He came back to the district he had represented from afar and ran for City Council to replace Huizar in 2020. Just a year into his term, he initiated a failed bid for mayor, a move that rubbed many in the district the wrong way.

“Most people look at De León and say he wasn’t there really to represent the people of the district, he was there to use it as a stepping stone to something else,” Sanchez said. “I don’t think his council colleagues are going to let him have any kind of role over the next couple of years. And so I basically think that he’s not doing a service to his constituents.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.