Cal State San Marcos to remove founder’s name from building over comment deemed racist

- Share via

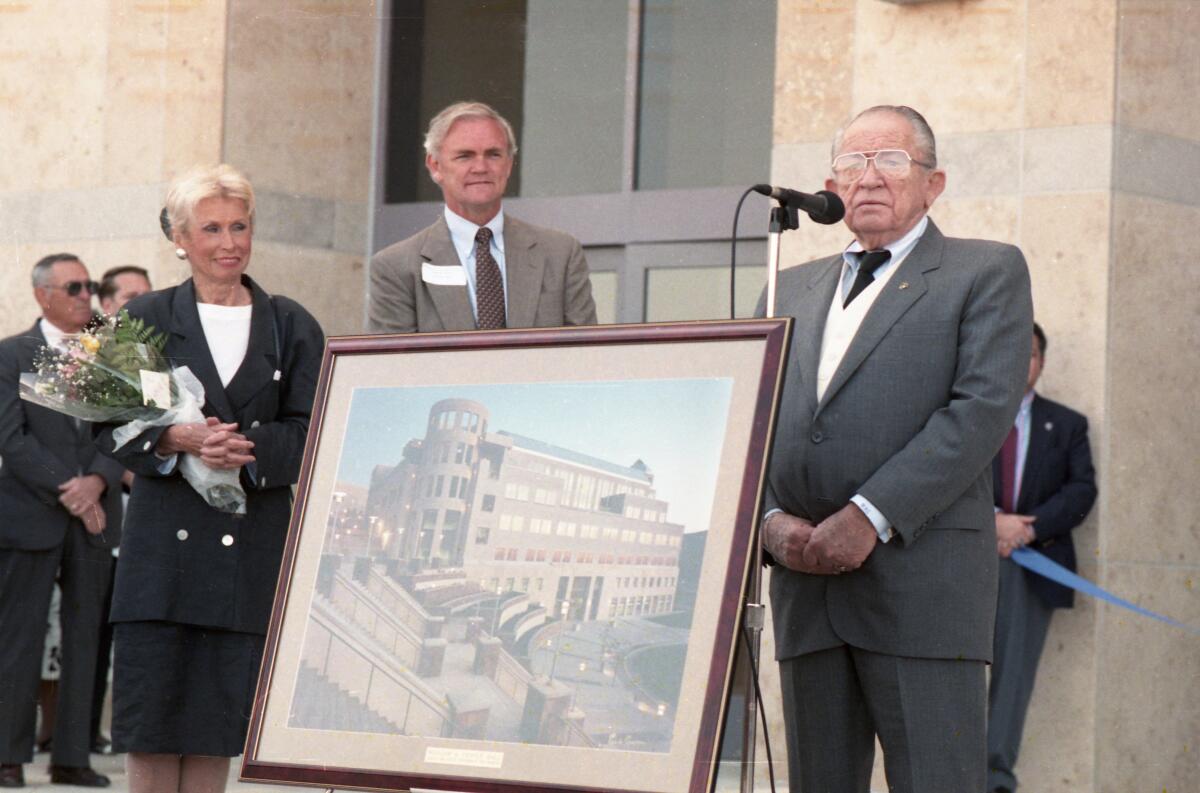

SAN DIEGO — There was a moment at Cal State San Marcos 30 years ago when many people looked at the school’s inaugural building and asked, “Should we really being naming this after our founder, Bill Craven?”

They were thinking of the Republican state senator from Oceanside who had worked to raise the money and support needed to give northern San Diego County something it badly wanted, its own university.

But in 1993, Craven infuriated many when he said that migrant workers “are perhaps on the lower scale of humanity for one reason or another.” He also appeared to target Latinos when a proposal arose to require Californians to carry state ID cards proving they were legal residents.

This story is for subscribers

We offer subscribers exclusive access to our best journalism.

Thank you for your support.

Angry faculty leaders urged school officials to drop the idea of naming the building after Craven. Administrators said no. They didn’t want to alienate him. And some thought the controversy would simply blow over.

That’s not how things turned out.

In a reflection of changing times nationally, Cal State San Marcos recently sought permission to take down Craven’s name. On Wednesday, mostly without discussion, the California State University Board of Trustees gave the go-ahead.

It did not end years of arguing and resentment.

Many educators say the decision is a step toward creating a more welcome feel at a school where the enrollment is now more than 50% Latino.

“Sen. Craven did some amazing work that we are so thankful for, including me,” said Elizabeth Matthews, a political science professor. “I have this job because this campus is here ... [But] this was the decision that needed to be made.”

Ken Lounsbery, an Escondido lawyer who was friends with the late senator for many years, sees this as an unfounded and spiteful act of political correctness.

“Calling Bill Craven a racist or white supremacist is slanderous,” Lounsbery said. “He had no prejudice.

“In the insular field of academics, it’s advantageous to win this kind of battle. And it’s pretty easy to tee-off on a dead man.”

Righting wrongs

Cal State San Marcos wasn’t stepping into the unknown in 2021 when its faculty senate began a new push to take Craven’s name off its administration building, the home of most student services.

In recent years, scores of schools have reexamined whether the words and deeds of the people whose names appeared on their buildings were socially acceptable. In many cases, the answer was no.

Harvard erased the name of Carter Glass, a former U.S. Treasury secretary who backed racist voter laws. Fresno State removed the name of Henry Madden, a Nazi sympathizer.

This intense period of introspection was brought on by many things, including the Black Lives Matter movement, the nation’s culture wars, social media and the rise of Generation Z, the most racially and ethnically diverse generation yet. They’re filling colleges from coast to coast.

The faculty senate referred the mater to a relative newcomer, Ellen Neufeldt, who became the school’s president in 2019.

She commissioned a task force of faculty, students, alumni, staff and community members to dig into Craven’s political life, particularly during the early 1990s, when a deep recession and high immigration led to a lot of hostility toward migrants in California.

“I didn’t have an outcome in mind,” Neufeldt told the Union-Tribune. “In fact, I was new enough that I really needed to understand more myself.”

The task force released its report in mid-January. Portions of the study characterize Craven as a racist. It also recommends that his name be removed from the building.

Street-level politician

Craven was a Philadelphia native who earned a degree in economics at Villanova University before enlisting in the Marines during World War II. He fought at Iwo Jima, a battle that killed nearly 7,000 Marines. He also was on active duty during the Korean War.

After that, he moved around, holding jobs that capitalized on his gift for communicating with people and remembering their names. He worked in radio, public relations, newspapers and sales.

His journeys eventually brought him to Oceanside, where he joined the planning commission, his springboard to a long career in government and politics. He served as city manager of San Marcos and a member of the county Board of Supervisors before winning election to the state Assembly and, later, the state Senate. He died in 1999 at age 78.

Craven was a fiercely independent moderate Republican who believed in bipartisanship and regularly supported bills filed by Democrats. He backed rent control, which was anathema to Republicans.

Craven constantly roamed his Senate district in northern San Diego County, catering to people’s interests. That led to his long quest to convince the state to place a university in the region. In 1978, the state gave him enough money to start a branch campus of San Diego State University in Vista. The satellite evolved into an independent school with its formal founding as Cal State San Marcos in 1989.

Migrant backlash

The university’s first students enrolled in fall 1990, when the state’s unemployment rate was 6.1%. It would rise to 9.8% two years later. The recession occurred while immigration was soaring, leading to a political backlash that included Proposition 187, which would have prevented undocumented immigrants from accessing social services and public education. It was approved by California voters in 1994 and later found to be unconstitutional.

Craven was a major political player during this time. His work included chairing a legislative committee on border issues that commissioned a study of the financial impact of undocumented people in San Diego County. As the task force report notes, he soon suggested that every school district and city in the county conduct a head count of suspected undocumented people who used public services.

Some people saw this as racist. Craven disagreed, saying he was trying to qualify the region for more federal funds.

His remarks about the humanity of migrants weren’t as easily explained.

The incident occurred on Feb. 5, 1993, during a Senate hearing on the legal status of children in San Diego County school districts. According to a transcript of the meeting, Craven said:

“There will be a lot of people who will disagree with what I am going to say and it is just a thought I had. It is not a philosophy.

“It seems rather strange that we go out of our way to take care of the rights of these individuals who are perhaps on the lower scale of our humanity for one reason or another, and we really spend a lot of time and, obviously, a lot of money to discommode the people who pick up the tab to care of the people that the law seems to favor. Is that correct? Well, maybe I should not ask that ...” (On a video of the hearing., the remarks are at the 1 hour, 27-minute mark.)

Craven was again accused of racism. He countered by saying that he was referring only to the “economic status” of undocumented immigrants.

Video adds context

Carleen Kreider, a business executive from Rancho Santa Fe, knew little about the historical controversy when she joined the task force, and initially thought “we were probably making too much of this.”

That changed when the group dug up a videotape of Craven delivering his remarks.

They were “hearing the words in context, not just that one sentence,” Kreider said. “Forty minutes [of tape] before and forty minutes after. I really felt sick to my stomach.”

It also was a turning point for Merryl Goldberg, a Cal State San Marcos music professor and member of the task force.

“For me, that was a total gut punch,” Goldberg said. “I really asked myself, ‘What do we do when this kind of rhetoric becomes public?’ We don’t let it slide.”

One of the comparatively few people to publicly come to Craven’s side in the past week was Tricia Craven Worley of San Diego, the late senator’s daughter.

She told CSU trustees during a hearing Tuesday that her father “was a public servant on the county and state levels with many notable achievements, Cal State San Marcos being the most important.”

“His mission was to make higher education available to the under-served in North County,” she said. “The current student body, over 50% of whom were Hispanic, demonstrates the fulfillment of this vision.

“The vitriolic slanders against him is based on a statement taken out of context 30 years ago. What the task force asserts is not fact, and it is not true ...

“Have you never said something you wish you had said another way?”

Some of this heartache might have been avoided if Craven had met with the faculty in 1993 and apologized for his words. He addressed their concerns in statements and to news reporters. But he never sat down with faculty to discuss the matter.

“Lots of people said [to the task force], look at the character of this man, look at all the good things he did,” Kreider said. “But why couldn’t he apologize? For me, that was really a deciding factor.”

President Neufeldt says the next steps will be deciding exactly when Craven’s name will be removed from the building, where to move a bust of the senator, and what to call the building in the future. A precise date for all of this has yet to be set.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.