- Share via

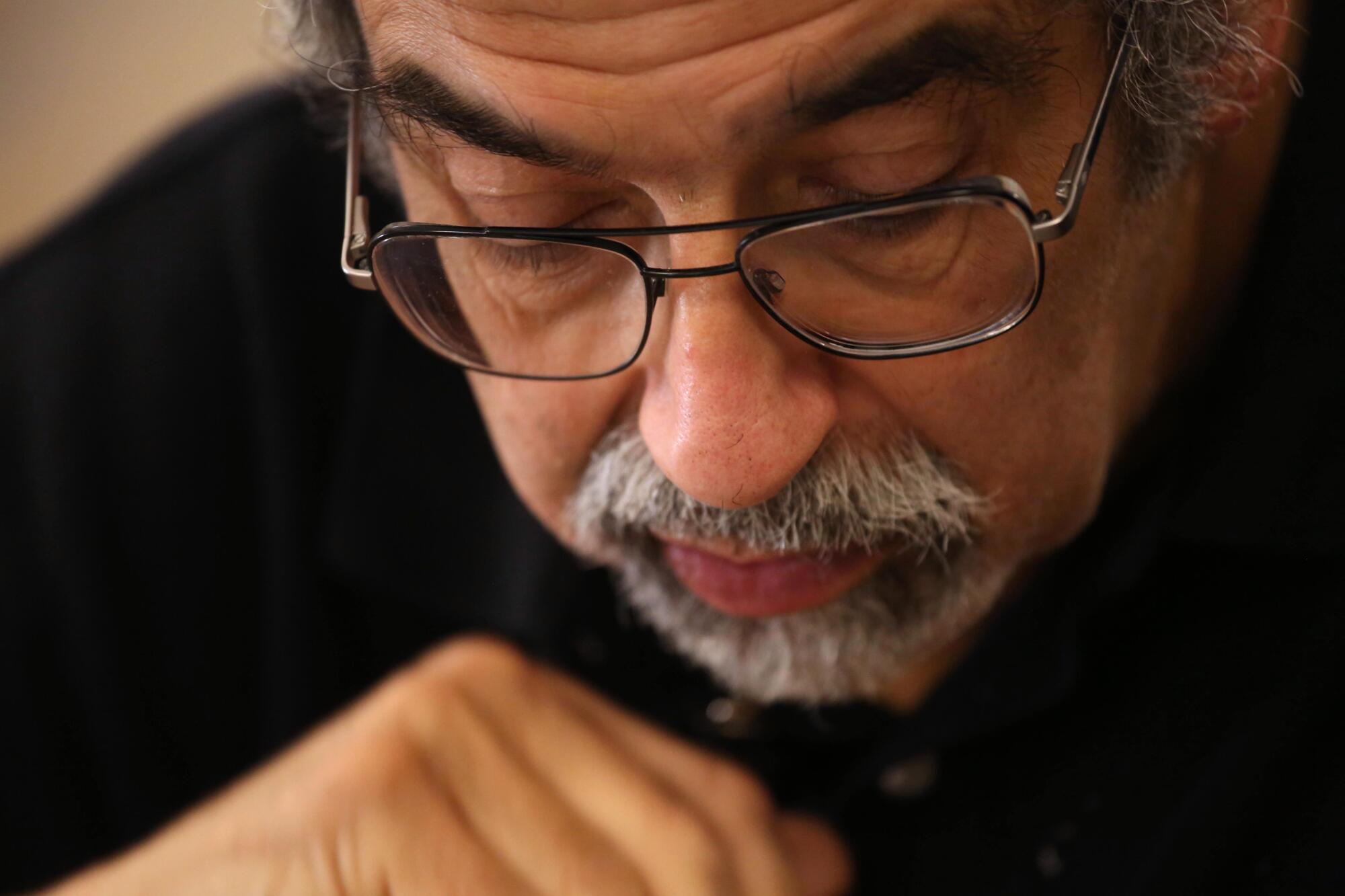

Mannie Rezende, a film buff, went to see a movie a few years ago and when it ended, he couldn’t remember where he had parked his car.

So he went home on a bus.

Mannie, 71, loves to read, but as soon as he finishes the L.A. Times or the New Yorker, he starts over again as if it’s his first read-through.

“It’s kind of heartbreaking,” said his wife, Rose, who has watched the man she married gradually lose himself in a thickening fog. “I feel like he’s just a shell of himself, and I think, ‘Oh, my God, I’m really alone even though he’s still here.’

“He’s disappearing on me.”

California is about to be hit by an aging population wave, and Steve Lopez is riding it. His column focuses on the blessings and burdens of advancing age — and how some folks are challenging the stigma associated with older adults.

Mannie is one of nearly 7 million people in the U.S. who have Alzheimer’s disease. That’s roughly 10% of the 65-and-older population, and the numbers are growing as the population ages.

As of yet, there is no surefire remedy — medicinal or therapeutic — to thwart a disease that makes people strangers to themselves as their loved ones bear cruel witness. But Rose wanted to share that she and Mannie have at least found a measure of support.

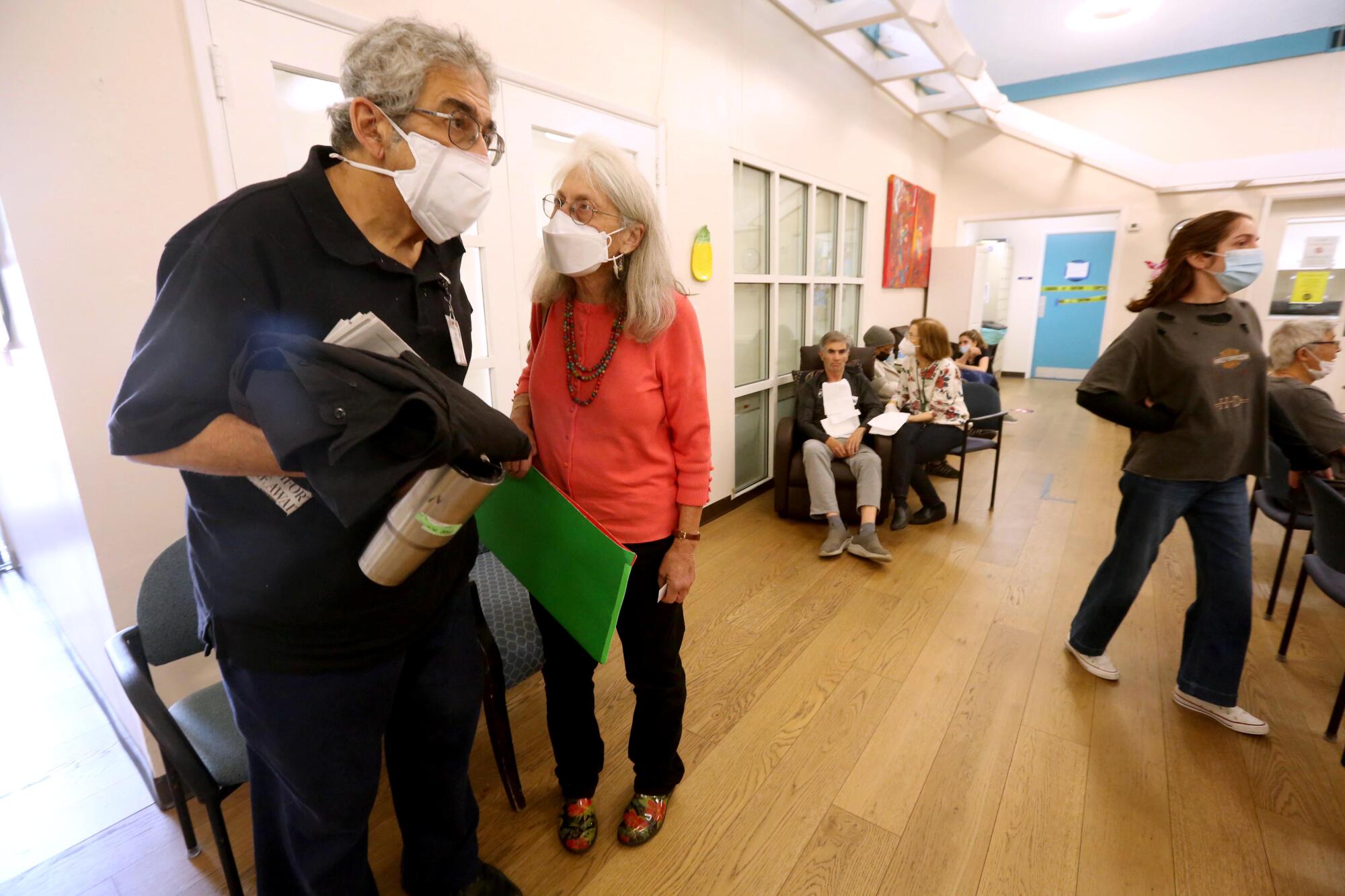

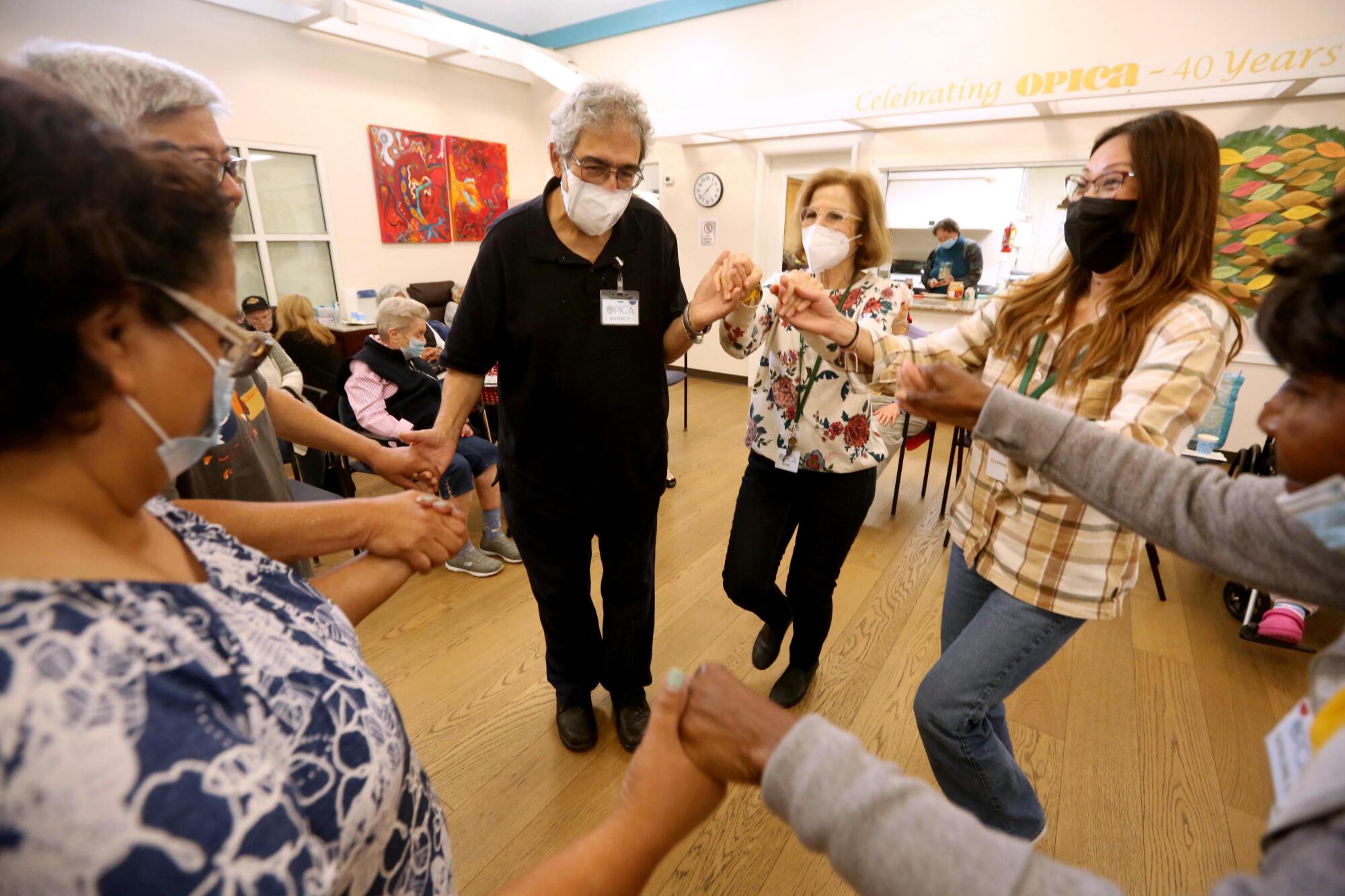

I met them on Monday just after 9 a.m. at a West Los Angeles adult day-care center called OPICA (Optimistic People in a Caring Community), a nonprofit founded more than four decades ago. Mannie and others with various forms and stages of dementia are engaged with group discussions, brain stimulation exercises, music, dancing, aerobics, art projects and strolls through adjacent Stoner Park.

“We can’t say that it improves their memory, but what we can say is that socialization is critical in terms of their mood and their health,” said Sara Kaye, OPICA’s director of family services.

This is also a way to keep members in their own homes rather than in nursing facilities. And while they’re busy at OPICA, their caregivers get breathers. For Rose, 69, that means focusing on her job as a family therapist. And she’ll have time to attend OPICA’s caregiver support meetings.

“Hi, Mannie,” one of the OPICA staffers called out as he entered the multipurpose room, where coffee and croissants were being served.

Mannie sat next to Kitty, another regular. It was not clear whether he recognized her, or any of the others, but he looked at ease, as if this was all familiar to him — and comfortable. He didn’t start conversations, but he listened in.

“Thank God, we’re so blessed to be here,” Kitty declared with a smile as bright as the sun. “What a nice day it’s going to be.”

Mannie always takes a copy of The Times to OPICA. He folds it, stuffs it into a back pocket, and pulls it out now and then. I told him that photographer Genaro Molina and I work for the paper and he nodded. A few hours later, I saw him reading the paper and I repeated the connection, but he seemed to have forgotten who we were.

Mannie has what the OPICA staff refers to as moderate impairment. As Rose put it, he can find his way to the bathroom in their Sunland home, but he might have trouble locating the laundry room or bedroom.

At OPICA, there’s a range of memory loss among the clientele; some have less cognitive loss, some have more. One man slept through several activities. Another gentleman, wearing a Lakers hat, held the hand of a staff member and stared at their intertwined fingers.

Mannie was an eager participant in the group warmup, waving an orange pom-pom to the beat of a Michael Jackson song. Then it was on to trivia and current events, a walk in the park, a performance by a guitar-strumming singer and art class, where Mannie worked on a watercolor painting.

When Mannie, Rose and I broke away for a few minutes to talk, he told me he was aware of his memory problems. “Especially compared to the old days, when I was younger,” he said. “It comes with the territory sometimes.”

You could observe Mannie and not suspect he has Alzheimer’s. He participates. He responds. When he danced, a smile appeared. But when he reaches inside himself, there is less to find than there used to be. Buried in the dust of time is his courtship of a young co-ed by the name of Rose, back when they were UCLA students who shared a passion for social justice and dreamed of a life together.

Mannie later worked in the university’s registrar’s office and mentored students, but the story of his life is less accessible now, and Rose says Mannie uses throwaway lines to keep conversations going.

When he has trouble with memory, Mannie told me, “there are workarounds.” He’s written things down, for example. “Chores. Upcoming events. Things we’re going to do and places where we’re going to go.”

Mannie, who likes sports and watches the Dodgers on TV, rooted for the Red Sox as a child in Connecticut. He remembered the name of the stadium where the team plays — Fenway Park — but did not seem to recall that he had just returned from a trip to see his family in the Hartford area.

Rose thinks about the Dylan Thomas line about not going “gentle into that good night,” but to instead “rage against the dying of the light.” And she thinks: If only that were possible.

“My job now is to help Mannie go kind of gently,” Rose said. “To not remind him he’s forgotten things.”

She and Mannie found OPICA during the pandemic, when the program temporarily went remote. Mannie liked it right away, and even more so when in-person sessions resumed. But Rose wonders how long she’ll be able to manage her job, and Mannie, and the $2,000 monthly cost of OPICA, where the capacity is limited to about 80 regular clients.

That brings up another of the many gargantuan challenges in a society that’s aging rapidly: Not enough of this kind of care is available despite growing need, not everyone can afford it, and in most cases, there is no insurance coverage. Mary Michlovich, OPICA’s director, awards “scholarships” to help some members defray costs, but she notes that in greater Los Angeles, there are only a handful of similar nonprofits.

The state administers dozens of adult day-care facilities with varying levels of service, some of which accept Medi-Cal coverage, but many counties have no such offerings. Sarah Steenhausen, a deputy director in the California Department of Aging, said the state is exploring ways to increase access and coverage, including for those who are neither wealthy enough to pay for care over long periods of time or poor enough to qualify for subsidies.

Dr. David Reuben, who runs UCLA’s Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care Program, said about 3,800 patients have received 24/7 access to medical care, counseling and other services there, and some are sent to OPICA for daytime activities.

Reuben told me he’s making the argument to congressional representatives and federal officials that Medicare could reduce costs by covering such models of care. Participants in his program, he said, have shorter hospital stays, fewer ER visits and reduced long-term nursing home stays, among other benefits.

Last month, Rose delivered a speech at an OPICA luncheon, thanking the staff. In the early days of Mannie’s Alzheimer’s, she said, it was as if they’d hit a sinkhole, then climb out to find steady ground “until suddenly there is another place where the ground gives way.” Mannie then got a bad case of COVID and his mental decline accelerated, leaving him lost and depressed until they found OPICA.

With all that love and support, Mannie looked forward to each day, despite long van rides from Sunland to West L.A. Lifted by a renewed sense of purpose, Rose said, Mannie’s emotional decline reversed and his cognitive decline slowed.

But she didn’t sugarcoat what they’re going through.

“Joy does not erase the grief. They sit side by side,” she said. “I know he will continue to grow downwards and backwards. It is heartbreaking. And yet it is also a poignant gift, to be allowed to see Mannie grow younger. … He is becoming sweeter, more childlike.”

Mannie loved the music of the ’60s, and Rose drew on that for a fitting end to her speech, quoting Ben E. King’s 1961 hit, “Stand By Me.”

“When the night has come

And the land is dark

And the moon is the only light we’ll see

No, I won’t be afraid ...

Just as long as you stand

Stand by me.”

For information on services for older adults, call the California Department of Aging information hotline at (1-800) 510-2020 or visit aging.ca.gov. For information on services for caregivers, visit caregivercalifornia.org.

steve.lopez@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.