Parkinson’s Disease: What We Know and Where Treatment Is Headed

- Share via

Key Facts

- Parkinson’s disease affects over 10 million people globally, with incidence increasing after age 60.

- Dopamine-producing neuron loss leads to both motor and non-motor symptoms, including tremors, sleep disturbances, and depression.

- Environmental exposures like pesticides and well water have been linked to PD, while caffeine and exercise may be protective.

- There is no cure for PD, but symptom management includes medications, physical therapy, and deep brain stimulation.

- Emerging research is targeting inflammation, α-synuclein aggregation, and lipid metabolism for new therapeutic pathways.

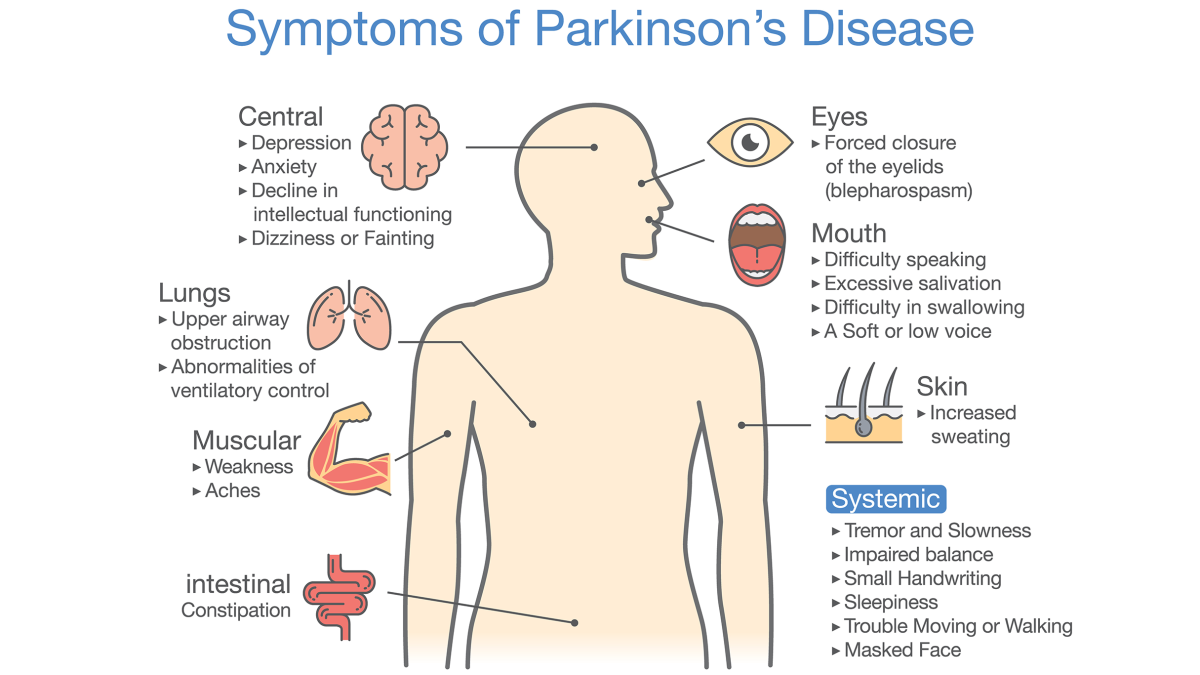

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is more than a movement disorder—it’s a neurological condition that reshapes the lives of patients and families. Parkinson’s affects both motor and non-motor functions so its impact is broad and multifaceted. While tremors and stiffness may be the most visible signs, PD also brings a wide range of symptoms that impact thinking, mood and overall functioning.

Common symptoms are bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor, postural instability, sleep disturbances and mood changes. As science digs deeper into this condition, hope grows for more precise, effective and compassionate care.

Table of Contents

- What Is Parkinson’s Disease?

- Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Epidemiology and Risk Factors

- Diagnostic Approaches

- Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Impairment and Related Disorders

- Inflammation, Biomarkers, and Future Directions

- Closing Thoughts

- References

What Is Parkinson’s Disease?

Parkinson’s disease is defined by the gradual loss of dopamine producing neurons in a part of the brain called the substantia nigra. This dopamine deficiency disrupts the brain circuits responsible for smooth and coordinated movements, leading to hallmark motor symptoms: resting tremor, muscle rigidity, slowness of movement (bradykinesia) and postural instability [1] [3] [5].

These are the most common Parkinson’s disease symptoms targeted by treatment. The hallmark motor symptoms encompass a range of movement symptoms and movement related symptoms that affect daily functioning. Postural instability often results in balance problems making coordination and stability difficult for patients. In addition to resting tremor, muscle rigidity, slowness of movement (bradykinesia) and postural instability, other motor symptoms such as freezing of gait and difficulty with fine motor tasks may also occur. Collectively these are referred to as PD symptoms, the clinical features of Parkinson’s disease.

But PD isn’t just about what the body can or can’t do—it’s also about what the brain feels. Long before a tremor appears many patients experience non-motor symptoms:

- Loss of smell (anosmia)

- Constipation

- REM sleep behavior disorder

- Depression and anxiety

- Subtle cognitive changes [1] [4] [7]

Parkinson’s symptoms, both motor and non-motor, can develop gradually and vary significantly between individuals. These symptoms can be easy to overlook or misattribute, often delaying diagnosis.

According to a 2008 review, clinicians rely on a detailed medical history and physical examination to distinguish PD from other parkinsonian syndromes [1], while a 2020 JAMA review emphasizes the role of dopamine transporter (DAT) imaging and clinical expertise in diagnosis and staging [5]. Parkinson’s is diagnosed primarily through evaluation of medical history and clinical examination, as there is no definitive blood test or brain scan for confirmation.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

So, what causes Parkinson’s disease? The short answer: it’s complicated. Most cases are considered idiopathic—meaning no single cause is identified—but multiple factors seem to converge. Both genetic and environmental factors are recognized as major contributors to the development of Parkinson’s disease.

Genetic contributions are increasingly recognized, with mutations in genes like LRRK2, PARK7 and SNCA playing a role [2]. Genetic mutations in these and other genes can influence disease development, sometimes interacting with environmental exposures. But genes don’t tell the whole story. Environmental exposures, such as pesticide use or heavy metals, also contribute, especially in individuals with underlying vulnerabilities.

At the cellular level PD is defined by several overlapping pathological processes:

- α-synuclein aggregation: This protein clumps abnormally into structures called Lewy bodies which disrupt neuron function [8] [12].

- Mitochondrial dysfunction: Neurons in PD often show signs of energy failure and impaired recycling of damaged components.

- Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress: Chronic immune activation leads to progressive neuronal injury.

- Impaired autophagy: The cell’s garbage disposal system breaks down, especially in chaperone-mediated processes, allowing toxic protein buildup [8].

- Dysregulated lipid metabolism: Emerging studies, including a 2025 paper, link altered fat processing to increased disease risk and progression [6].

The loss of dopamine producing neurons in the substantia nigra involves the degeneration and death of specific brain cells and nerve cells which underlies the motor and non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

These mechanisms interact like a feedback loop—fueling one another and accelerating neurodegeneration. This complex interplay drives the disease process, shaping both the progression and development of Parkinson’s disease.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Parkinson’s disease affects more than 10 million people worldwide, with incidence rising sharply with age—especially after 60 [11]. Most Parkinson’s disease cases are idiopathic and occur in older adults, with the majority of diagnoses in people over 60.

However, early onset cases, known as early onset PD, can develop before age 50 and may differ in disease progression, diagnosis and treatment compared to typical cases. Men are more frequently affected than women, and rural living, well water exposure and pesticide contact are established risk factors.

On the other hand, researchers have also identified protective factors. Regular caffeine consumption, moderate nicotine exposure and consistent physical activity may lower PD risk. Though not fully understood, these factors may influence inflammation, neuroplasticity or dopamine metabolism.

Diagnostic Approaches

There’s no single test for Parkinson’s, which makes early and accurate diagnosis a clinical challenge. Physicians typically rely on:

- Detailed history and neurological exam

- Positive response to dopaminergic therapy (like levodopa)

- Neuroimaging, especially DAT-SPECT scans, which assess dopamine transporter availability [5]

- Genetic testing to identify inherited forms of Parkinson’s disease

In advanced diagnostic settings a spinal tap (lumbar puncture) may be performed to collect spinal fluid for biomarker analysis, such as detecting abnormal alpha-synuclein proteins.

New frontiers are expanding diagnostic accuracy. Machine learning algorithms are being trained to analyze voice patterns, gait dynamics and digital biomarkers.

AI-enhanced diagnostics and bioinformatics platforms are also being developed to detect early inflammatory signals before motor symptoms emerge [10]. Autonomic testing, including monitoring for blood pressure changes, may be used to assess non-motor symptoms.

Distinguishing Parkinson’s disease from other syndromes is crucial, with multiple system atrophy being an important differential diagnosis due to overlapping symptoms but differing disease progression and treatment responses.

Treatment Strategies

While there’s no cure for PD, treatment can significantly improve quality of life. The primary goal of therapy is to manage symptoms and help patients maintain independence.

Medications:

- Levodopa therapy is the gold standard, especially effective in the early stages of Parkinson’s disease, as it replenishes brain dopamine levels.

- Dopamine agonists like pramipexole act directly on dopamine receptors.

- MAO-B inhibitors (e.g., selegiline) prevent dopamine breakdown.

- Amantadine and anticholinergics help with tremor and dyskinesia [5] [9] [12].

Medication is different from surgery and should be discussed with a doctor. Dopaminergic medications can cause orthostatic hypotension and low blood pressure so monitoring is important.

Non-medication is equally important:

- Exercise and physical therapy improves mobility, balance and mood [5] [9].

- Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is used for patients with severe motor fluctuations or medication side effects. Participate in clinical trials to help advance new treatments and future options.

PD can also affect mood, behavior and cognition. Managing neuropsychiatric symptoms like depression or hallucinations requires a nuanced approach, including SSRIs, atypical antipsychotics and cognitive behavioral therapy.

The Parkinson’s Foundation is a key player in advancing research and treatment for Parkinson’s disease.

Cognitive Impairment and Related Disorders

As the disease progresses many patients develop cognitive impairment, from mild forgetfulness to full blown Parkinson’s Disease Dementia (PDD). These symptoms can overlap with or mimic Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) (also known as Lewy body dementia) and Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) and other disorders within the spectrum of atypical parkinsonism, so accurate diagnosis is critical.

A 2025 study compared cognitive trajectories across these syndromes and emphasized the need for tailored care and better biomarkers to distinguish between them.

Inflammation, Biomarkers and Future Directions

Inflammation is no longer seen as just a consequence of PD—it may be the cause. Recent studies, including a 2025 paper using machine learning and bioinformatics, have identified new inflammatory markers that could help with early diagnosis [10]. Ongoing Parkinson’s research is key to finding new biomarkers, better treatments and a cure.Researchers are also finding potential therapeutic targets.

For example, UPS10, a protein that blocks α-synuclein degradation, may be a way to stop disease progression [8]. And lipid metabolism pathways open up metabolic interventions. These therapeutic strategies aim to modify the disease process to slow or stop progression.

This is driving personalized medicine where treatment is based on a patient’s genetic, metabolic or inflammatory profile. And the average life expectancy for most people with PD is the same as the general population thanks to research and care.

Conclusion

Parkinson’s disease is still a challenge for patients, caregivers and clinicians. But it’s also a global research effort to understand the onset, progression and treatment of the disease. As we understand the interplay of genetics, environment and inflammation the future of PD looks more precise and hopeful. Until then a multidisciplinary approach – medication, therapy and emotional support – is the foundation of good care.

[1] Jankovic J. (2008). Parkinson’s disease: clinical features and diagnosis. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 79(4), 368–376. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2007.131045

[2] Kalia, L. V., & Lang, A. E. (2015). Parkinson’s disease. Lancet (London, England), 386(9996), 896–912. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3

[3] Marino, B. L. B., de Souza, L. R., Sousa, K. P. A., Ferreira, J. V., Padilha, E. C., da Silva, C. H. T. P., Taft, C. A., & Hage-Melim, L. I. S. (2020). Parkinson’s Disease: A Review from [4] Pathophysiology to Treatment. Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry, 20(9), 754–767. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389557519666191104110908

[5] Balestrino, R., & Schapira, A. H. V. (2020). Parkinson disease. European journal of neurology, 27(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14108

[6] Armstrong, M. J., & Okun, M. S. (2020). Diagnosis and Treatment of Parkinson Disease: A Review. JAMA, 323(6), 548–560. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.22360

[7] Qin, B., Fu, Y., Raulin, A. C., Kong, S., Li, H., Liu, J., Liu, C., & Zhao, J. (2025). Lipid metabolism in health and disease: Mechanistic and therapeutic insights for Parkinson’s disease. Chinese medical journal, 10.1097/CM9.0000000000003627. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000003627

[8] Bloem, B. R., Okun, M. S., & Klein, C. (2021). Parkinson’s disease. Lancet (London, England), 397(10291), 2284–2303. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00218-X

[9] Anisimov, S., Takahashi, M., Kakihana, T., Katsuragi, Y., Sango, J., Abe, T., & Fujii, M. (2025). UPS10 inhibits the degradation of α-synuclein, a pathogenic factor associated with Parkinson’s disease, by inhibiting chaperone-mediated autophagy. The Journal of biological chemistry, 110292. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2025.110292

[10] Halli-Tierney, A. D., Luker, J., & Carroll, D. G. (2020). Parkinson Disease. American family physician, 102(11), 679–691. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33252908/

[11] Li, Y., Jia, W., Chen, C., Chen, C., Chen, J., Yang, X., & Liu, P. (2025). Identification of biomarkers associated with inflammatory response in Parkinson’s disease by bioinformatics and machine learning. PloS one, 20(5), e0320257. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0320257

[12] Tysnes, O. B., & Storstein, A. (2017). Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Journal of neural transmission (Vienna, Austria : 1996), 124(8), 901–905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-017-1686-y