Why REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Is a Warning Sign for Parkinson’s and Other Brain Diseases

- Share via

Key Facts

- RBD is marked by loss of REM sleep atonia, leading to physical dream enactment.

- Polysomnography is essential to confirm RBD and rule out other disorders.

- Idiopathic RBD is a strong predictor of Parkinson’s and dementia with Lewy bodies.

- Melatonin and clonazepam are the most commonly used treatments.

- RBD patients often show early signs of neurodegeneration before clinical diagnosis.

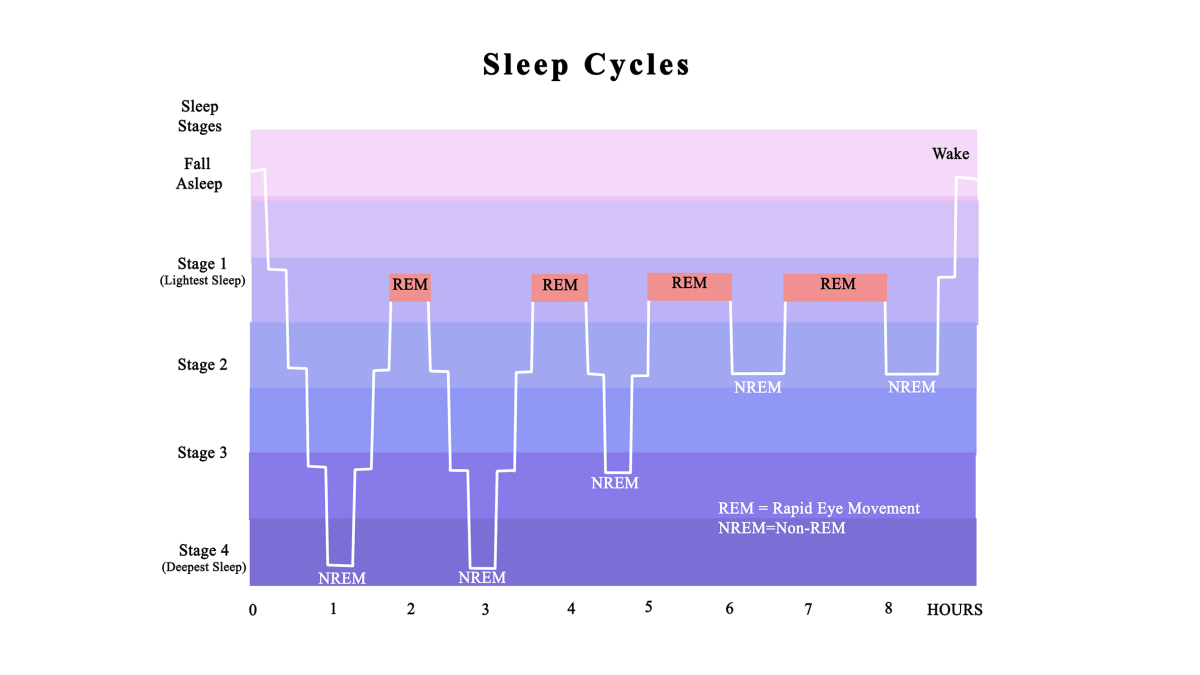

REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD) might sound like something out of a sleepwalker’s nightmare, but it’s a very real—and increasingly important—sleep disorder. RBD occurs when the normal muscle paralysis, known as muscle atonia, during REM (rapid eye movement) sleep disappears, allowing individuals to physically act out their dreams during dream sleep.

REM sleep is one of several sleep stages, also referred to as paradoxical sleep or active sleep, and is characterized by rapid eye movements and vivid dreaming. This loss of muscle atonia can involve anything from flailing limbs to more aggressive or even violent behaviors, potentially resulting in injury to the sleeper or their bed partner.

Once seen as a rare curiosity, RBD is now recognized as both a disruptive parasomnia and a warning sign of more serious neurological conditions—especially neurodegenerative disorders known as synucleinopathies, such as Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body dementia, and multiple system atrophy (MSA). This dual significance places RBD at a unique crossroads between sleep medicine and neurology.

Table of Contents

- Diagnosis: Beyond the Bedroom

- Treatment: From Safety to Disease Modification

- RBD as a Window to Neurodegenerative Disorders

- Emerging Risk Factors and Experimental Research

- Closing Thoughts

- References

Diagnosis: Beyond the Bedroom

Pinpointing RBD isn’t just about noticing odd behavior at night. While many patients (or more often, their partners) report vivid, sometimes violent dream enactment, true diagnosis requires polysomnography—an overnight sleep study that records brain activity, muscle tone, and eye movements. RBD diagnosis relies on identifying abnormal behaviors during the REM stage of the sleep cycle. Specifically, clinicians look at the REM stage as a specific sleep stage for the presence or absence of muscle atonia—REM sleep without atonia indicates a loss of the muscle paralysis that should naturally occur during this phase.

According to a 2017 review in Mayo Clinic Proceedings [1], this diagnostic confirmation is vital—not just to guide treatment, but also to identify those at heightened risk for developing a neurodegenerative disorder.

And that risk is real. A 2025 study titled The Many Faces of REM Sleep Behavior Disorder [4] found that individuals with idiopathic RBD (i.e., RBD not linked to medications or other causes) have a significant chance of developing Parkinson’s or DLB within a decade. This makes RBD one of the most robust prodromal biomarkers in neurology today.

Treatment: From Safety to Disease Modification

First and foremost, in managing RBD, we need to keep patients and partners safe. That often means adapting the sleep environment—removing sharp objects, padding furniture, or even sleeping separately if necessary. RBD often coexists with other sleep disorders which can complicate management and require a comprehensive approach. But pharmacological treatment can also be very effective.

Two drugs are front runners:

- Clonazepam, a benzodiazepine long considered the gold standard, is effective but carries risks—particularly sedation, confusion, and increased fall risk in older adults. Note that some medications can suppress REM sleep which can impact symptom control and overall sleep quality.

- Melatonin, a natural hormone that regulates sleep, is gaining popularity for its safer profile. Multiple studies show its efficacy is comparable to clonazepam in many patients [2] [3]. Sleep medicine reviews have summarized the efficacy and safety of current and emerging therapies for RBD, providing a scientific basis for treatment decisions.

The 2025 International RBD Study Group consensus [2] also explores new territory, finding potential benefit from cholinesterase inhibitors like rivastigmine and dopamine agonists such as pramipexole. However, these are still under investigation and treatment must be individualized based on symptom severity, age and co-existing conditions.

Good sleep hygiene and lifestyle modifications are also important. Avoiding sleep deprivation and ensuring a sufficient sleep period helps promote enough sleep and enough REM sleep which are critical for overall health and RBD management.

RBD as a Window to Neurodegenerative Disorders

Perhaps the most exciting—and urgent—aspect of RBD is its predictive value. Multiple studies show RBD isn’t just a symptom; it may be an early sign that the brain is already undergoing neurodegenerative changes long before other signs appear. REM sleep plays a crucial role in brain development and maintaining the brain’s ability to process information and regulate emotions, making its disruption particularly important in the context of RBD.

Advanced neuroimaging and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers have shown early pathology in many patients with idiopathic RBD. This aligns with broader research on alpha-synuclein accumulation in the brain—key in Parkinson’s and DLB development [5].

A 2020 review in Frontiers in Neurology [3] reminds us we need to watch for neurologic signs. Ongoing brain research and sleep research will continue to uncover why REM sleep is important for early detection of neurodegenerative changes. That means screening not only for motor symptoms but for early cognitive changes—because acting out dreams today could mean dementia tomorrow.

Emerging Risk Factors and Experimental Research

New studies are looking at what might contribute to or worsen RBD risk and severity. These are early days but here are some findings:

- A 2025 Neurology study [7] found long-term consumption of ultraprocessed foods may be linked to prodromal Parkinson’s signs, including RBD. The mechanism is unknown but may be related to systemic inflammation or gut-brain axis dysfunction.

- Research in Sleep [8] has highlighted preoptic glutamatergic neurons which regulate REM suppression in mouse models. This may lead to targeted, non-sedating treatments for RBD and related conditions.

- In psychiatric populations, disrupted REM sleep is common—and RBD may coexist or be mistaken for other conditions. A 2025 Médecine/Sciences review [6] emphasizes how sleep quality, mood and neurological health are intertwined.

A full night’s sleep typically has four or five cycles of alternating REM and NREM sleep (also called non REM sleep). Each sleep cycle has light sleep, deep sleep and REM (also called paradoxical sleep or desynchronized sleep). During the deep sleep stage of NREM, breathing slows, blood pressure drops and the immune system is boosted.

REM sleep (also called active sleep, dream sleep or rapid eye movement REM) is characterized by rapid eye movements, vivid dreaming and variable brain waves. Most people experience REM sleep several times a night. Sleep cycles repeat throughout the night and after each cycle a new sleep cycle begins. Adults need seven to nine hours of sleep to complete enough cycles for optimal health.

Sleep deprivation or a shortened sleep period can reduce enough REM sleep and deep sleep leading to negative health outcomes.Obstructive sleep apnea and other sleep disorders can disrupt sleep architecture reducing sleep time and quality of both REM and NREM sleep. Daytime naps can supplement nighttime sleep and help those who haven’t slept enough at night.

Sleep medicine reviews and sleep research have shown the importance of maintaining healthy sleep cycles for the brain to function and overall well-being. These findings support a holistic approach to RBD care—one that considers sleep hygiene, lifestyle and even dietary factors as part of the treatment.

Conclusion

REM Sleep Behavior Disorder is no longer just a sleep curiosity—it’s a diagnostic warning sign that may sound years before neurodegenerative disease sets in. While traditional treatments like clonazepam and melatonin work for symptom control, newer research points to the possibility of disease interception.

As we learn more about sleep, neurobiology and behavior, RBD may become a key entry point for early intervention in Parkinson’s, DLB and related conditions. The future of sleep medicine will shape the future of neurology—and for those with RBD that’s good news.

References

[1] St Louis, E. K., & Boeve, B. F. (2017). REM Sleep Behavior Disorder: Diagnosis, Clinical Implications, and Future Directions. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 92(11), 1723–1736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.09.007

[2] During, E. H., Malkani, R., Arnulf, I., Kunz, D., Bes, F., De Cock, V. C., Ratti, P. L., Stefani, A., Schiess, M. C., Provini, F., Schenck, C. H., & Videnovic, A. (2025). Symptomatic treatment of REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD): A consensus from the international RBD study group - Treatment and trials working group. Sleep medicine, 132, 106554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2025.106554

[3] Roguski, A., Rayment, D., Whone, A. L., Jones, M. W., & Rolinski, M. (2020). A Neurologist’s Guide to REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. Frontiers in neurology, 11, 610. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00610

[4] Arnaldi, D., Mattioli, P., Orso, B., Massa, F., Pardini, M., Morbelli, S., Nobili, F., Figorilli, M., Casaglia, E., Mulas, M., Terzaghi, M., Capriglia, E., Malomo, G., Solbiati, M., Antelmi, E., Pizza, F., Biscarini, F., Puligheddu, M., & Plazzi, G. (2025). The Many Faces of REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. Providing Evidence for a New Lexicon. European journal of neurology, 32(4), e70169. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.70169

[5] Hu M. T. (2020). REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD). Neurobiology of disease, 143, 104996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2020.104996

[6] Coelho, J., Samalin, L., Yrondi, A., Iftimovici, A., Philip, P., & Micoulaud-Franchi, J. A. (2025). La santé du sommeil comme marqueur et cible d’intervention dans les troubles psychiatriques [Sleep health as a marker and target for health interventions in psychiatric disorders]. Medicine sciences : M/S, 41(5), 477–489. https://doi.org/10.1051/medsci/2025065

[7] Wang, P., Chen, X., Na, M., Flores-Torres, M. H., Bjornevik, K., Zhang, X., Chen, X., Khandpur, N., Rossato, S. L., Zhang, F. F., Ascherio, A., & Gao, X. (2025). Long-Term Consumption of Ultraprocessed Foods and Prodromal Features of Parkinson Disease. Neurology, 104(11), e213562. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000213562

[8] Mondino, A., Jadidian, A., Toth, B. A., Hambrecht-Wiedbusch, V. S., Floran-Garduno, L., Li, D., York, A. K., Torterolo, P., Pal, D., Burgess, C. R., Mashour, G. A., & Vanini, G. (2025). Regulation of REM and NREM Sleep by Preoptic Glutamatergic Neurons. Sleep, zsaf141. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsaf141