How Traumatic Brain Injury Affects the Brain and Body Over Time

- Share via

Key Facts

- TBI triggers both primary mechanical damage and delayed secondary injuries like inflammation and neurodegeneration.

- Cognitive effects may include memory loss, mood swings, and impaired social judgment.

- The hippocampus is especially vulnerable, disrupting learning and memory formation.

- Older adults with TBI face an elevated risk of dementia and functional decline.

- Treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach, integrating mental and physical rehabilitation.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) doesn’t stop at impact. TBI is a spectrum, from mild to severe, with different symptoms and outcomes. Whether it’s a fall, car crash, motor vehicle accidents, child abuse or a battlefield blast, TBI sets off a chain reaction in the brain and body that can last for years. Shaken baby syndrome, a form of closed brain injury caused by child abuse, is an example of how rough handling of infants can cause serious brain trauma.

The more we learn, the more we realize: TBI is not just a head injury. While head injuries and brain injuries are related, TBI refers to trauma that disrupts normal brain function. It’s a whole body condition with far reaching consequences for thinking, feeling and functioning, sometimes resulting in permanent disability or death.

This article will explain what happens during and after TBI, the evolving science of treatment and why long term care and awareness matter more than ever. Unlike many neurological disorders, TBI is often preventable with safety measures and awareness.

Table of Contents

- Pathophysiology: From Initial Impact to Chronic Damage

- Systemic and Cognitive Effects

- Treatment Strategies: Current and Emerging Approaches

- Closing Thoughts

- References

Pathophysiology: From Initial Impact to Chronic Damage

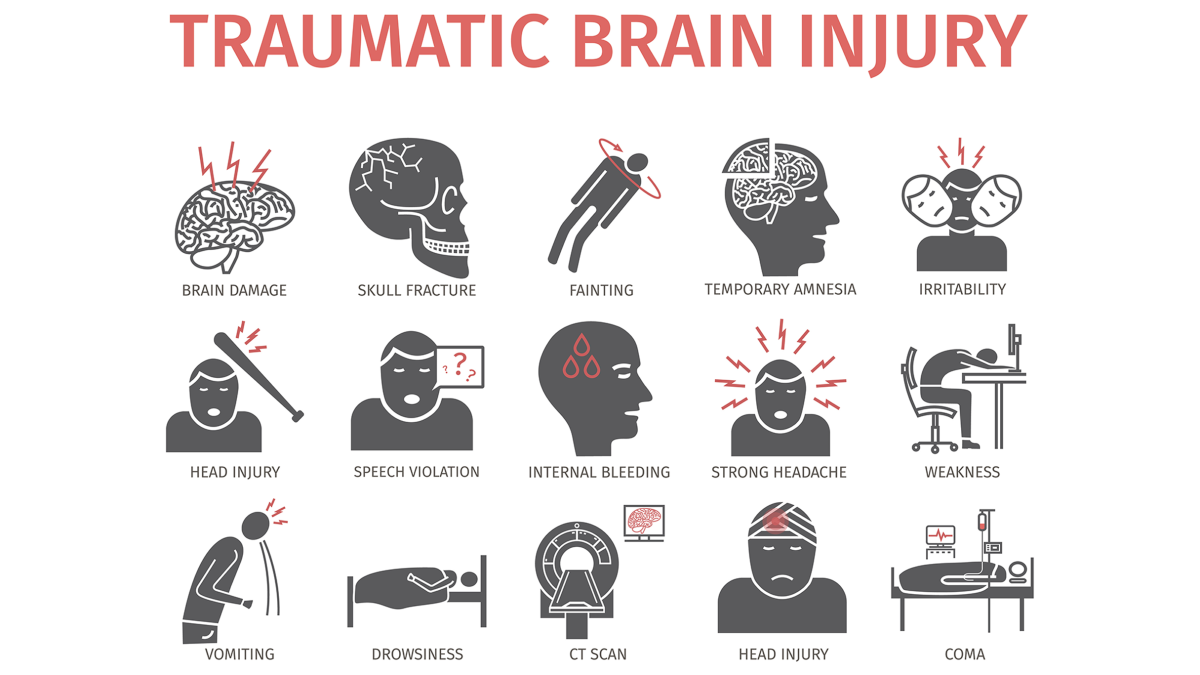

The story of TBI starts with the initial trauma – the primary brain injury. This is the immediate, brain caused physical damage to brain tissue and brain cells from a blow to the head, often from motor vehicle collisions, falls or explosions. Common types are closed head injury and non penetrating TBI, where the skull remains intact, compared to penetrating TBI where an object breaches the skull and brain tissue, including trauma like concussions. Severe trauma can also cause skull fractures.

In some cases, both penetrating and non-penetrating TBIs can occur in the same person, highlighting the complexity of head trauma. But it’s what happens next, in the hours, days and even months after that causes most of the long term damage. Secondary injuries occur as the brain tries to recover. These include inflammation, oxidative stress and excitotoxicity – a biochemical overreaction that can damage neurons.

Damage to blood vessels can lead to complications such as blood clots, further damaging brain tissue. Microscopic injuries like diffuse axonal injury and axonal injury can occur, often undetectable with standard imaging but resulting in significant impairment. Managing blood pressure and interventions to relieve pressure inside the skull are crucial in preventing further damage.

A 2021 review in the Journal of Neuroimmunology notes that this secondary damage isn’t limited to the brain; it triggers systemic effects that ripple throughout the body [1].

Researchers in Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience have identified several of these secondary cascades as potential therapeutic targets – especially in the context of long term damage, including neurodegeneration and glial scarring [4].

Systemic and Cognitive Effects

Social Cognition and Emotional Regulation

After a moderate or severe TBI, people often find themselves struggling with more than just memory lapses. Changes in mood, personality and social behaviour are common – and they can be just as debilitating as physical symptoms. According to a 2021 review in the Handbook of Clinical Neurology, survivors may experience apathy, impulsivity, irritability and difficulty interpreting facial expressions or social cues [8].

These effects can isolate individuals from friends, family and the workplace, often leading to depression or anxiety. Emotional dysregulation after TBI isn’t a character flaw – it’s a neurological consequence of brain trauma.

Learning, Memory and Synaptic Plasticity

The hippocampus, the brain’s memory centre, is particularly vulnerable in TBI. Damage here disrupts synaptic plasticity – the brain’s ability to adapt and form new connections. A 2025 study in The Neuroscientist found that TBI interferes with both long term potentiation and memory retention, especially in developing or aging brains [9].

In simpler terms, recovering from TBI is like trying to learn new information with a foggy chalkboard – memories don’t stick as easily and retrieval becomes harder over time.

Aging and Chronicity

Time doesn’t heal all wounds, especially when it comes to TBI. Aging exacerbates the long term effects, with older adults at higher risk of dementia, degenerative brain diseases, reduced functional independence, persistent communication problems, physical complications, disrupted sleep patterns and cumulative brain atrophy. A 2021 article in the Journal of Neurotrauma notes that the chronic effects of TBI are most pronounced later in life, especially for those with repeated injuries or delayed treatment [7].

These findings have prompted public health experts to call for more long term surveillance and care planning for aging TBI survivors – especially as the population of older adults continues to grow due to the long term consequences of TBI.

Treatment Strategies: Current and Emerging Approaches

TBI treatment has come a long way – but we’re still scratching the surface when it comes to effective therapies.

A 2017 article in Cell Transplantation outlines current options – anti-inflammatory medications, neuroprotective drugs, physical and occupational therapy and cognitive rehabilitation programs [2]. In some cases, surgical interventions may be necessary to relieve intracranial pressure or remove damaged tissue.

For mild traumatic brain injury (mild TBI) which often presents with symptoms like headache, dizziness and confusion, treatment is focused on treating symptoms and monitoring for worsening symptoms.

Most people with mild TBI recover fully within a few weeks, although some may experience persistent symptoms. A healthcare provider should monitor recovery and approve return to activities. Healthcare providers use neuropsychological tests, MRI, CT scan and blood tests to diagnose and assess TBI. For moderate to severe cases, a rehabilitation team is essential for planning and delivering comprehensive recovery programs.

But translating lab findings into everyday clinical care is difficult. The variability in outcomes especially in moderate to severe TBI and severe brain injury where no single treatment fits all. These cases may require intensive treatment and patients can sometimes enter a minimally conscious state after injury.

Assessment of consciousness often involves evaluating responses to external stimuli and using tools like the Glasgow Coma Scale to determine severity. This is especially true in military contexts where blast injuries, PTSD and chronic pain often overlap.

A 2010 article in The Psychiatric Clinics of North America notes the need for integrated care – addressing both the psychological and physiological impact of combat related brain injury [3]. Organizations such as the national institute (NIH) and human services agencies play a key role in supporting TBI research, diagnosis and care.

Closing Thoughts

Globally, traumatic brain injuries are a leading cause of death and disability especially in young adults and the elderly. Brain injuries and head injuries are major public health concerns worldwide. In the US alone, 223,000 hospitalizations and 69,000 deaths were attributed to TBI in 2021 according to the CDC. [6]

A 2020 review in The Medical Clinics of North America notes the importance of rapid diagnosis and individualized care pathways [5]. A 2021 Journal of Neurotrauma review argues for a shift in focus – from short term survival to long term quality of life [10]. Identifying risk factors is key to prevention, research and improving outcomes as the long term consequences of TBI can have a big impact on individuals and society.

TBI’s impact isn’t just personal – it’s societal. From healthcare costs to lost productivity the ripple effects are huge, but awareness and access to care is uneven especially in underserved communities.

References

[1] Sabet, N., Soltani, Z., & Khaksari, M. (2021). Multipotential and systemic effects of traumatic brain injury. Journal of neuroimmunology, 357, 577619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2021.577619

[2] Galgano, M., Toshkezi, G., Qiu, X., Russell, T., Chin, L., & Zhao, L. R. (2017). Traumatic Brain Injury: Current Treatment Strategies and Future Endeavors. Cell transplantation, 26(7), 1118–1130. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963689717714102

[3] Meyer, K. S., Marion, D. W., Coronel, H., & Jaffee, M. S. (2010). Combat-related traumatic brain injury and its implications to military healthcare. The Psychiatric clinics of North America, 33(4), 783–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2010.08.007

[4] Ng, S. Y., & Lee, A. Y. W. (2019). Traumatic Brain Injuries: Pathophysiology and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience, 13, 528. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2019.00528

[5] Capizzi, A., Woo, J., & Verduzco-Gutierrez, M. (2020). Traumatic Brain Injury: An Overview of Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Medical Management. The Medical clinics of North America, 104(2), 213–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2019.11.001

[6] Maas, A. I., Stocchetti, N., & Bullock, R. (2008). Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. The Lancet. Neurology, 7(8), 728–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70164-9

[7] Rabinowitz, A. R., Kumar, R. G., Sima, A., Venkatesan, U. M., Juengst, S. B., O’Neil-Pirozzi, T. M., Watanabe, T. K., Goldin, Y., Hammond, F. M., & Dreer, L. E. (2021). Aging with Traumatic Brain Injury: Deleterious Effects of Injury Chronicity Are Most Pronounced in Later Life. Journal of neurotrauma, 38(19), 2706–2713. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2021.0038

[8] Rabinowitz, A. R., Kumar, R. G., Sima, A., Venkatesan, U. M., Juengst, S. B., O’Neil-Pirozzi, T. M., Watanabe, T. K., Goldin, Y., Hammond, F. M., & Dreer, L. E. (2021). Aging with Traumatic Brain Injury: Deleterious Effects of Injury Chronicity Are Most Pronounced in Later Life. Journal of neurotrauma, 38(19), 2706–2713. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2021.0038

[9] Eyolfson, E., Suesser, K. R. B., Henry, H., Bonilla-Del Río, I., Grandes, P., Mychasiuk, R., & Christie, B. R. (2025). The effect of traumatic brain injury on learning and memory: A synaptic focus. The Neuroscientist : a review journal bringing neurobiology, neurology and psychiatry, 31(2), 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/10738584241275583

[10] Haarbauer-Krupa, J., Pugh, M. J., Prager, E. M., Harmon, N., Wolfe, J., & Yaffe, K. (2021). Epidemiology of Chronic Effects of Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of neurotrauma, 38(23), 3235–3247. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2021.0062