Pseudomembranous Colitis (Clostridium Difficile Infection): Risks and Treatment Strategies

- Share via

Key Facts

- Pseudomembranous colitis is usually caused by Clostridium difficile overgrowth after antibiotic use.

- TcdA and TcdB toxins from C. difficile damage the colon and cause inflammation.

- Symptoms include diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, and blood in stools.

- Metronidazole and vancomycin are common treatment options based on disease severity.

- Preventing PMC starts with smart antibiotic use and proper hygiene in healthcare settings.

Table of Contents

- What Is Pseudomembranous Colitis?

- Pathophysiology: How PMC Develops

- Risk Factors and Clinical Presentation

- Diagnosis

- Treatment Options

- Prevention is Key

- Closing Thoughts

- References

What is Pseudomembranous Colitis?

Pseudomembranous colitis (PMC) is an antibiotic associated severe inflammatory condition of the colon caused by an overgrowth of Clostridium difficile (C. difficile), a toxin producing bacterium. It’s known for forming yellow-white plaques – called pseudomembranes – on the lining of the colon which can be seen during colonoscopy or on histology [1], [6]. Although often linked to antibiotic use, PMC can present with a wide range of severity from mild diarrhea to life threatening colitis.

Pathophysiology: How PMC Develops

While Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile) is the primary organism behind PMC, it’s not the only one. Other pathogens have occasionally been found to cause similar colonic inflammation and pseudomembrane formation [1], [3]. But C. difficile is the most common and clinically relevant.

The process starts with antibiotics. These medications while useful for treating bacterial infections can disrupt the balance of normal colonic flora in the gut. This gives C. difficile – often present in small amounts in the intestines – the opportunity to flourish [2], [7], [9]. Spores that were once dormant now find an environment ripe for growth.

C. difficile produces two potent toxins, toxin A (TcdA) and toxin B (TcdB). These toxins bind to cells lining the colon, damaging them and setting off a cascade of inflammation. In severe cases the body’s immune response and cell damage leads to the hallmark pseudomembranes seen in PMC [5].

Risk Factors and Clinical Presentation

Not all antibiotic therapy is created equal, but broad spectrum agents like clindamycin, cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones are often implicated. These drugs wipe out a wide range of gut flora making room for C. difficile to flourish [10].

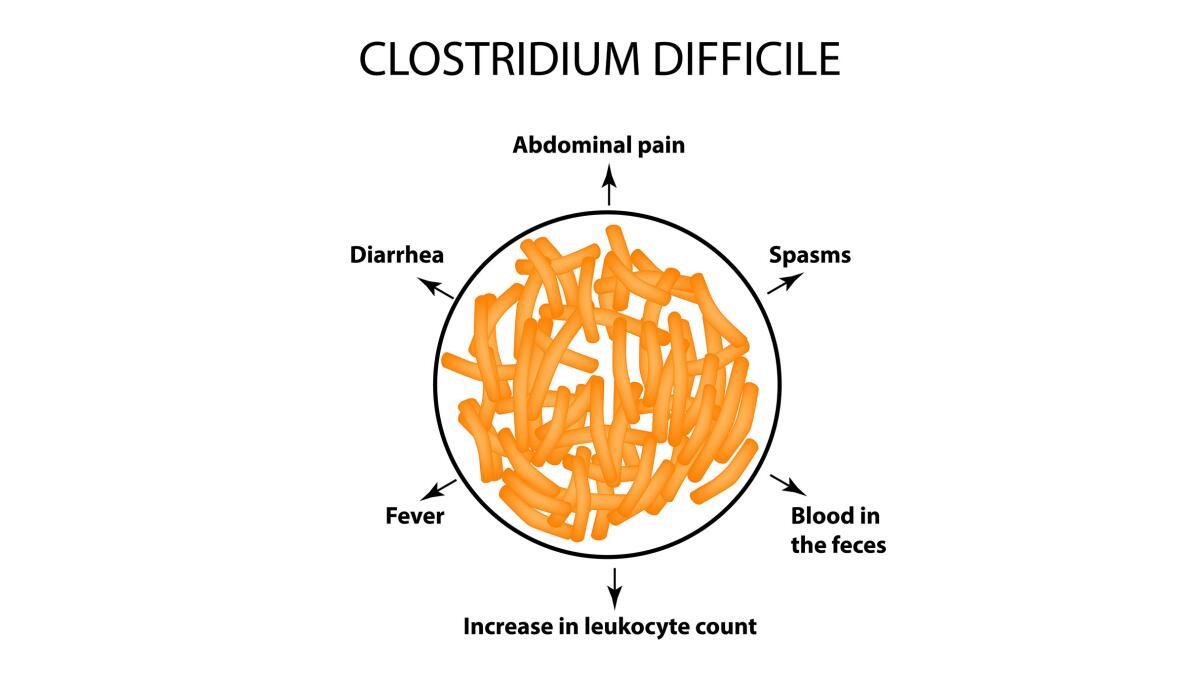

Symptoms

PMC symptoms often start during or shortly after antibiotics:

- Watery diarrhea (can be mild or profuse)

- Abdominal cramps or pain

- Fever

- Blood or mucus in stools [4]

- Bloody diarrhea

These symptoms can overlap with other conditions but the timing, especially after antibiotics, is a key clue.

Severity Spectrum

PMC doesn’t affect everyone the same way. While some people have mild diarrhea others can spiral into severe colitis and complications like:

- Fulminant colitis

- Toxic megacolon

- Perforation of the colon

These cases need urgent medical attention.

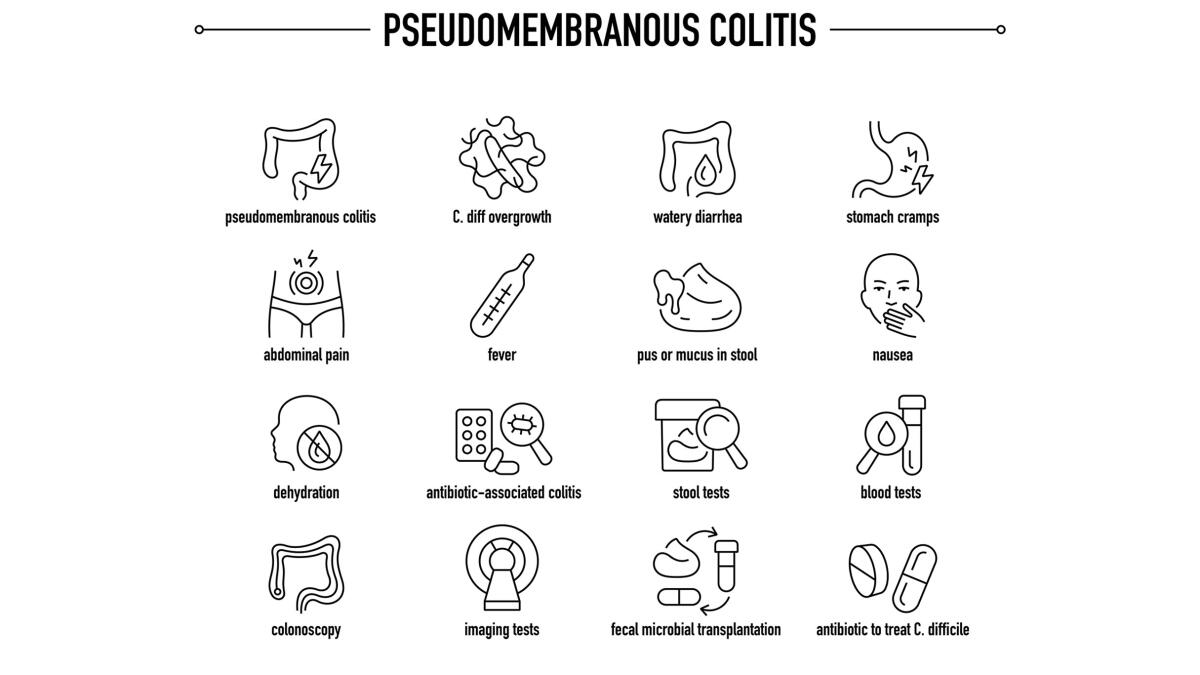

Diagnosis

Healthcare providers consider PMC when a patient on antibiotics develops sudden or worsening diarrhea, so rapid diagnosis is key. But diagnosing it isn’t always easy.

- Stool tests for C. difficile toxins or DNA are commonly used but not all tests are created equal [4].

- Endoscopy may reveal the pseudomembranes especially in more advanced or unclear cases.

- Histological examination of colon tissue can confirm inflammation and membrane formation which is particularly useful when the cause isn’t C. difficile [6].

Treatment Options

Metronidazole: Metronidazole is used for mild to moderate PMC. It’s effective, cheap and oral [1], [8]. But it’s being replaced by other treatments due to higher relapse rates and slower symptom resolution.

Vancomycin: Oral vancomycin is now the go to for severe or complicated C. difficile infections. It stays in the gut (where it’s needed) without being absorbed into the bloodstream so it targets the infection locally.

PMC relapses so recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection is common. Some patients may need extended vancomycin tapers, fidaxomicin (a newer antibiotic) or even fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT).

FMT involves restoring healthy gut bacteria by transplanting stool from a donor—a treatment that’s showing promising results in recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection cases [4].

Prevention is Key

One of the best ways to prevent PMC is smart antibiotic prescribing. Avoiding unnecessary prescriptions especially broad spectrum antibiotics can help preserve the natural gut microbiome and prevent C. difficile overgrowth.

Hospitals and healthcare facilities also have a role to play by enforcing infection control measures such as hand hygiene and isolation protocols to limit the spread of C. difficile spores.

Closing Thoughts

Pseudomembranous colitis is more than just a complication of antibiotic use—it’s a serious gastrointestinal illness that needs timely diagnosis and treatment. Understanding the underlying disruption of gut microbiota and toxin production is key to managing and preventing this condition. As we learn more about PMC the emphasis remains on prevention through good antibiotic stewardship and early intervention when symptoms occur.

References

[1] Surawicz, C. M., & McFarland, L. V. (1999). Pseudomembranous colitis: causes and cures. Digestion, 60(2), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1159/000007633

[2] Janoir C. (2016). Virulence factors of Clostridium difficile and their role during infection. Anaerobe, 37, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.10.009

[3] Tang, D. M., Urrunaga, N. H., & von Rosenvinge, E. C. (2016). Pseudomembranous colitis: Not always Clostridium difficile. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine, 83(5), 361–366. https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.83a.14183

[4] Surawicz, C. M., & McFarland, L. V. (2000). Pseudomembranous Colitis Caused by C. difficile. Current treatment options in gastroenterology, 3(3), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11938-000-0023-x

[5] Castagliuolo, I., & LaMont, J. T. (1999). Pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of Clostridium difficile infection. The Keio journal of medicine, 48(4), 169–174. https://doi.org/10.2302/kjm.48.169

[6] Farooq, P. D., Urrunaga, N. H., Tang, D. M., & von Rosenvinge, E. C. (2015). Pseudomembranous colitis. Disease-a-month : DM, 61(5), 181–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.disamonth.2015.01.006

[7] Trnka, Y. M., & Lamont, J. T. (1984). Clostridium difficile colitis. Advances in internal medicine, 29, 85–107. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6369936/

[8] Brar, H. S., & Surawicz, C. M. (2000). Pseudomembranous colitis: an update. Canadian journal of gastroenterology = Journal canadien de gastroenterologie, 14(1), 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1155/2000/324025

[9] Counihan, T. C., & Roberts, P. L. (1993). Pseudomembranous colitis. The Surgical clinics of North America, 73(5), 1063–1074. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46141-4

[10] Weymann L. H. (1982). Colitis caused by Clostridium difficile: a review. The American journal of medical technology, 48(11), 927–934. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6758571/