Understanding Anal Fissures: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment Options

- Share via

Key Facts

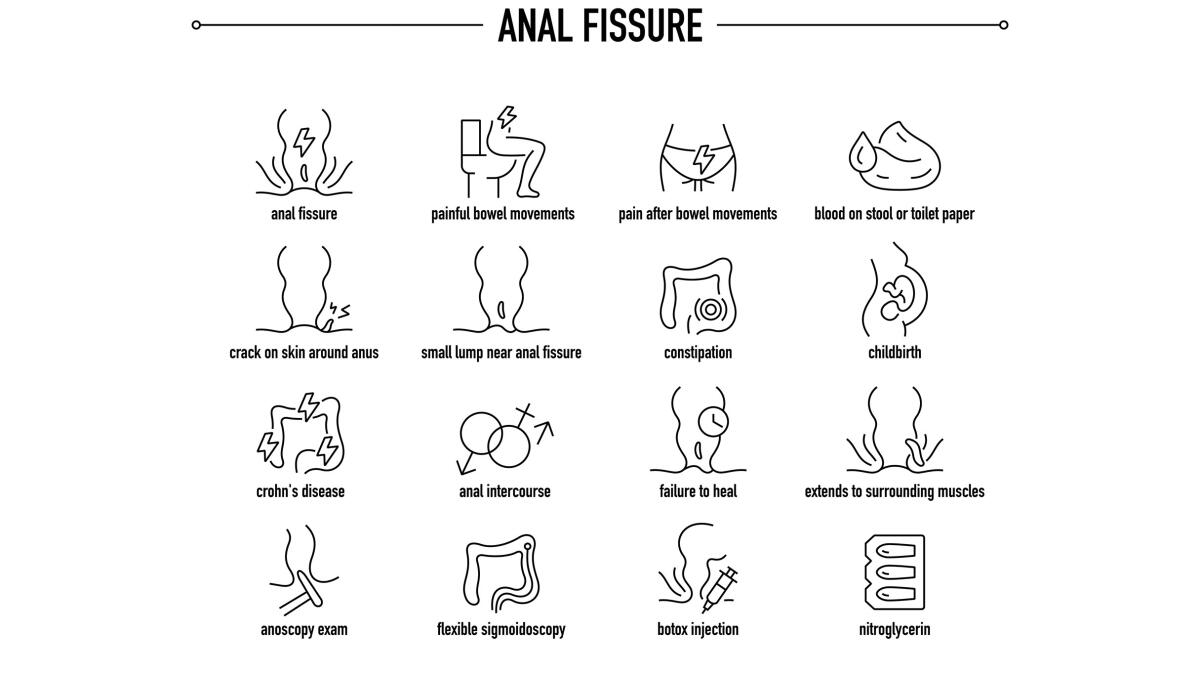

- Anal fissures are small tears in the lining of the anal canal.

- They can cause sharp pain and bleeding, especially during or after bowel movements.

- Anal fissures can be acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term).

- Common causes include constipation, straining, and hard stools.

- Treatments range from self-care to medical procedures like topical ointments or surgery.

Anal fissures may be small in size, but they can cause a surprisingly big impact on a person’s comfort and quality of life. These painful tears in the thin lining of the anal canal—known as the anoderm—can make something as simple as using the bathroom a dreaded experience.

Fortunately, understanding what causes them, how they present, and what treatment options are available can go a long way toward relieving symptoms and preventing recurrence. Lifestyle and dietary modifications, such as increasing fiber intake and staying hydrated, can help prevent anal fissures.

Table of Contents

- What Are Anal Fissures?

- Types of Anal Fissures

- Clinical Presentation

- Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Prevalence and Significance

- Closing Thoughts

- References

What Are Anal Fissures?

Anal fissures are small, linear tears or cracks (a small tear; a fissure is a small break in the lining) that develop in the anoderm, the delicate tissue just inside the anus, usually below the dentate line. They often result from trauma, such as when people pass hard stools or hard or large stools, and are commonly associated with high pressure in the internal anal sphincter muscle. This muscle spasm can reduce blood flow to the area, impair healing, and worsen the condition over time [1], [4], [5].

Anal fissures typically present with sharp pain and anal pain during or after a bowel movement. Common symptoms of anal fissures include pain, bleeding, and discomfort. The sharp pain can last from a few minutes to a few hours after a bowel movement.

In terms of prevalence, anal fissures are among the most frequently reported anorectal conditions—second only to hemorrhoids in outpatient visits [9], [10]. Most anal fissures heal within a few weeks with proper care.

Despite their benign nature, the pain and bleeding they cause can be significant enough to interfere with daily activities, even compared to anal fistulas. Anal fissures and hemorrhoids can have similar symptoms, such as rectal bleeding, but hemorrhoids are swollen veins located in the lower rectum [2].

Types of Anal Fissures

Not all anal fissures are the same. They can be classified by cause and duration:

Primary Fissures:

- These fissures occur spontaneously, typically due to mechanical trauma like straining during bowel movements or anal intercourse. They’re often associated with high anal sphincter tone, meaning a tight anal sphincter muscle increases the risk of tearing during defecation.

- The tension and spasms in the anal muscles, particularly the anal sphincter muscles, play a significant role in the development and persistence of fissures [6].

Secondary Fissures:

- Secondary fissures are linked to underlying health conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (including Crohn’s disease), sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, or even certain types of cancer such as colon cancer.

- Because these are driven by systemic or chronic inflammatory processes, they may be more resistant to standard treatment [3]. In such cases, evaluation and management by a rectal surgeon may be necessary.

Acute vs. Chronic Fissures:

- Acute fissures are new tears that typically resolve within a few weeks with conservative treatment, such as stool softeners and topical creams.

- Chronic fissures last over eight weeks and may show scarring or a skin tag. Medical or surgical treatment is often needed, including lateral internal sphincterotomy, botulinum toxin injections, or topical calcium channel blockers. While surgery is typically most effective for chronic cases, it carries a small risk of complications.

Clinical Presentation

Anal fissures typically present with sharp pain and anal pain during bowel movements. Common symptoms of anal fissures include a sudden, intense sharp pain that is often described as “passing glass.” This anal pain can last for a few minutes to a few hours after a bowel movement.

Other symptoms of anal fissures include:

- Rectal bleeding—bright red blood on toilet paper or on the surface of the stool (as opposed to being mixed in)—which occurs due to small tears in the lining and involvement of blood vessels.

- Itching or irritation around the anus due to inflammation or attempts at healing [8].

Because anal fissures and other anorectal conditions, such as hemorrhoids or abscesses, can have similar symptoms—including rectal bleeding and anal pain—a proper diagnosis is key. A physical exam is often enough, though chronic or atypical fissures might require further testing.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The causes of anal fissures, or causes of anal tears, are most often related to trauma from passing hard stools or straining to pass hard stools during a bowel movement. These hard stools can stretch and tear the delicate lining of the anal canal, which is a short tube at the end of the large intestine.

The anal canal is surrounded by anal muscles, including the anal sphincter muscles, which play a key role in both the development and healing of fissures. When a fissure forms, the anal sphincter muscles may spasm or tighten, further reducing blood flow and hindering healing.

The most common trigger is trauma from passing hard or large stools. When combined with increased pressure in the internal anal sphincter, the anal tissue becomes more prone to tearing. Once a fissure forms, the body often reacts by tightening this muscle further, creating a cycle of poor blood flow and delayed healing [4], [5].

Other contributing factors include:

- Chronic constipation

- Frequent diarrhea

- Childbirth or anal sex

- Reduced anodermal blood flow, especially in older adults [7]

To prevent constipation and reduce the risk of anal fissures, adopting a high fiber diet—rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains—along with adequate hydration, is recommended. These measures help keep stools soft and formed, making them easier to pass and minimizing trauma to the anal canal.

This pathophysiology explains why some fissures heal quickly, while others become chronic and resistant to simple treatments.

Prevalence and Significance

Anal fissures are not just common—they’re a top reason people seek evaluation for rectal pain. In fact:

- They are the second most common anorectal condition after hemorrhoids [10].

- They account for a significant number of outpatient visits to colorectal and gastroenterology clinics each year [9].

A colon and rectal surgeon or rectal surgeon may be involved in the diagnosis and treatment of anal fissures, especially in chronic or complicated cases. Persistent symptoms may require evaluation to rule out colon cancer and other possible complications. Early recognition allows for timely medical treatment and better outcomes.

Recognizing their symptoms early and understanding the types of fissures can help patients avoid complications and minimize discomfort.

Closing Thoughts

Anal fissures are painful yet common anorectal conditions characterized by tears in the anal lining, often due to high sphincter pressure and trauma. While acute fissures may heal with basic self-care, chronic cases often need medical or surgical management.

Recognizing symptoms early—especially lingering pain and bleeding—can lead to faster treatment and better outcomes. If you or someone you know experiences these signs regularly, it’s worth consulting a healthcare provider for guidance.

To learn more, explore additional guidance from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons or read recent updates from Cleveland Clinic and MedlinePlus.

References

[1] Salati S. A. (2021). Anal Fissure - an extensive update. Polski przeglad chirurgiczny, 93(4), 46–56. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0014.7879

[2] Boland, P. A., Kelly, M. E., Donlon, N. E., Bolger, J. C., Larkin, J. O., Mehigan, B. J., & McCormick, P. H. (2020). Management options for chronic anal fissure: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. International journal of colorectal disease, 35(10), 1807–1815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-020-03699-4

[3] Schlichtemeier, S., & Engel, A. (2016). Anal fissure. Australian prescriber, 39(1), 14–17. https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2016.007

[4] Beaty, J. S., & Shashidharan, M. (2016). Anal Fissure. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery, 29(1), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1570390

[5] Zaghiyan, K. N., & Fleshner, P. (2011). Anal fissure. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery, 24(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1272820

[6] Herzig, D. O., & Lu, K. C. (2010). Anal fissure. The Surgical clinics of North America, 90(1), . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2009.09.002

[7] Jonas, M., & Scholefield, J. H. (2001). Anal Fissure. Gastroenterology clinics of North America, 30(1), 167–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70172-2

[8] Lubowski D. Z. (2000). Anal fissures. Australian family physician, 29(9), 839–844. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11008386/

[9] Akinmoladun, O., & Oh, W. (2024). Management of Hemorrhoids and Anal Fissures. The Surgical clinics of North America, 104(3), 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2023.11.001

[10] Lyle, V., & Young, C. J. (2024). Anal fissures: An update on treatment options. Australian journal of general practice, 53(1-2), 33–35. https://doi.org/10.31128/AJGP/05-23-6843