Managing Generalized Epilepsy: Treatment Strategies and Personalized Care

- Share via

Key Facts

- Levetiracetam reduces tonic-clonic seizures by over 77% in clinical studies.

- Ethosuximide is highly effective for absence seizures, especially in children.

- Valproate remains the gold standard for multiple generalized seizure types.

- Psychiatric conditions often co-occur with epilepsy and need simultaneous management.

- Emergency care for seizures typically starts with benzodiazepines per 2024 ACEP guidelines.

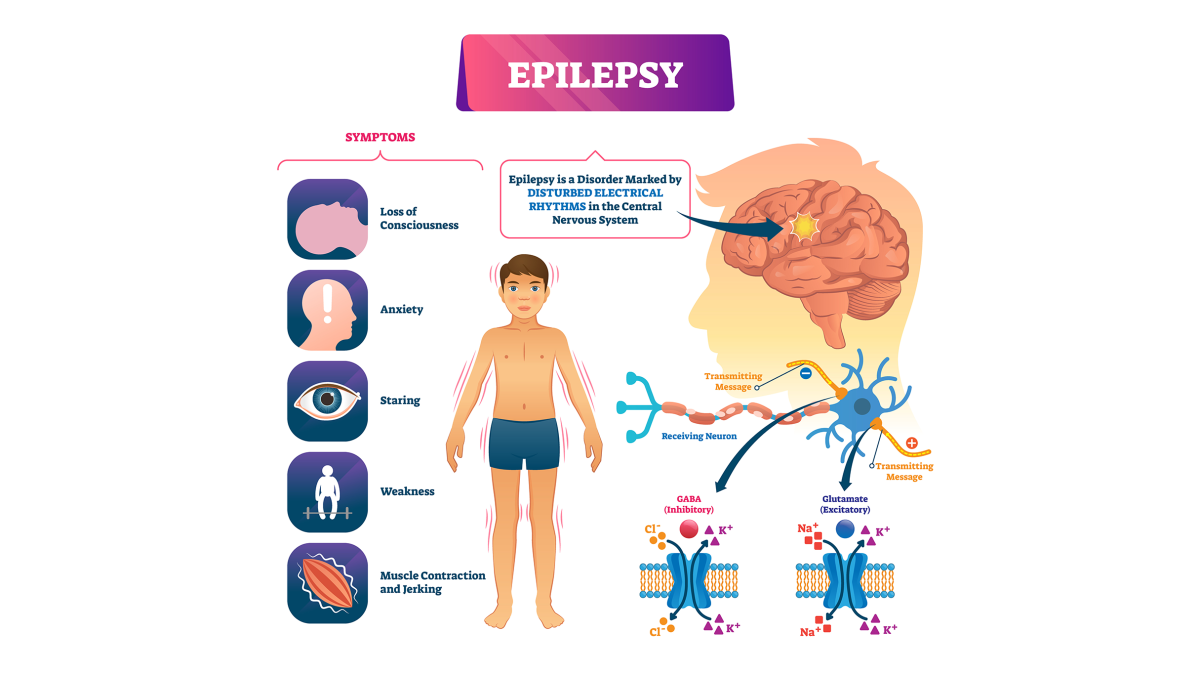

Generalized epilepsy is a type of seizure disorder, a chronic neurological condition often used interchangeably with epilepsy, where abnormal brain activity affects both sides of the brain from the start. In epilepsy, damaged or abnormal brain cells generate abnormal electrical activity, leading to epileptic seizures.

These epileptic seizures are characterized by specific seizure symptoms, which can vary depending on the types of seizures involved. There are different types of seizures, including generalized and focal seizures, and understanding seizure symptoms helps guide diagnosis and treatment. These seizures can take various forms—like tonic-clonic (grand mal), absence (petit mal), or myoclonic—and can profoundly impact a person’s daily life, safety, and mental well-being.

Thankfully, early diagnosis and evidence-based treatment with broad-spectrum antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) offer many patients the chance to achieve meaningful seizure control and long-term stability.

Table of Contents

- First-Line Treatment Options

- Personalized Medication Strategy

- Management of Specific Syndromes

- Risk and Seizure Triggers Management

- Emergency Management Considerations for Status Epilepticus

- Broader Clinical Context in Epilepsy Treatment

- Closing Thoughts

- References

First-Line Treatment Options

Broad-Spectrum AEDs for Generalized Seizures

The cornerstone of treatment for generalized epilepsy is the use of broad-spectrum AEDs—medications that are effective across a variety of seizure types. According to expert guidelines, the leading first-line options include:

- Valproic acid (500–2000 mg/day, divided BID)

- Lamotrigine (100–400 mg/day, divided BID)

- Levetiracetam (1000–3000 mg/day, divided BID) [2]

These agents have shown consistent effectiveness in treating generalized tonic-clonic, absence, and myoclonic seizures. Broad-spectrum AEDs are designed to reduce seizure frequency and help patients become seizure free, which are key goals in epilepsy management. However, certain seizure types respond even better to more targeted medications.

For example, ethosuximide (500–1500 mg/day, BID) is particularly effective for absence seizures and is often used in pediatric cases [5]. The goal of first-line therapy is not only to control current seizures but also to prevent future seizures.

What the FDA Data Shows

Clinical trials reinforce the strength of these therapies:

- Levetiracetam led to a 77.6% median reduction in generalized tonic-clonic seizure frequency, compared to 44.6% with placebo in a large double-blind trial [3].

- Perampanel, another approved AED, demonstrated similar success, cutting seizure frequency by 76% versus 38% with placebo [4].

These outcomes support the use of these agents not just as first-line treatments but also in cases requiring additional control. Effective treating epilepsy with these medications significantly reduces the risk of future seizures and improves long-term outcomes.

Personalized Medication Strategy

Managing epilepsy isn’t one-size-fits-all. A personalized approach to medication selection can help people with epilepsy improve outcomes and reduce side effects:

- Start with monotherapy—a single AED—titrated slowly to balance efficacy with tolerability.

- Monitor blood drug levels, patient-reported side effects, and overall adherence during routine follow-ups.

- When selecting medications, consider family history of epilepsy, other risk factors (such as previous brain injury or genetic predisposition), and individual patient characteristics.

- Discontinuing AEDs may be considered after 2–5 years of seizure freedom, but only under the guidance of a neurologist [2] .

Adjusting therapy based on factors like age, reproductive plans (especially in women), psychiatric comorbidities (including mental illness), and side effect profiles helps tailor care to each patient’s lifestyle and medical needs.

Management of Specific Syndromes

Generalized epilepsy includes several epilepsy syndromes, each with distinct features such as age of onset, seizure types, and underlying causes. Each syndrome comes with its own best practices for epilepsy treatment:

- Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy (JME): Valproate is the gold standard. However, lamotrigine and topiramate are useful alternatives—especially in women of childbearing age, where valproate is often avoided due to teratogenic risk [6].

- Childhood Absence Epilepsy: First-line treatments include ethosuximide, valproate, and lamotrigine, depending on the child’s tolerance and response to the drug [5].

- Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizures: Valproate remains highly effective, especially for idiopathic generalized epilepsy [7].

Understanding the relationship between epilepsy and seizures is crucial for selecting the right therapy. Epilepsy treatment may include medication, lifestyle changes, and, in cases of drug-resistant epilepsy, epilepsy surgery may be considered to reduce seizure frequency and improve quality of life.

Recognizing the specific epilepsy syndrome is key to choosing the right therapy and setting realistic expectations for long-term seizure control.

Risk and Seizure Triggers Management

While medication forms the backbone of treatment, managing seizure triggers is equally important. Patients and caregivers should be educated on:

- Avoiding sleep deprivation, alcohol, medication non-adherence, and low blood sugar, all of which can lower seizure threshold or trigger seizures.

- Keeping consistent dosing schedules to maintain stable drug levels.

- Wearing medical ID bracelets and training family members in seizure first aid to ensure safety in emergencies.

Head injury and traumatic brain injury are important risk factors that can trigger seizures in susceptible individuals. When triggered by these risk factors, seizures affect the brain by disrupting normal nerve activity, which can lead to widespread or localized neurological effects depending on the seizure type.

Lifestyle consistency can make a dramatic difference in seizure frequency and severity.

Emergency Management Considerations for Status Epilepticus

When breakthrough seizures occur—or if a patient arrives at the emergency department in a prolonged seizure (status epilepticus)—immediate care is critical. The 2024 ACEP clinical policy recommends:

- First-line: Benzodiazepines (like lorazepam)

- Second-line: Phenytoin, levetiracetam, or valproate if seizures persist [1]

Emergency management may also be required after a first seizure, particularly if it is an unprovoked seizure, as these cases carry a higher risk of recurrence and warrant careful evaluation. The occurrence of a second seizure, especially if both are unprovoked, often prompts the initiation of long-term antiseizure treatment.

These protocols ensure rapid stabilization and minimize the risk of long-term neurological damage.

Broader Clinical Context in Epilepsy Treatment

Accurate diagnosis is critical. Not all seizures that look generalized are truly generalized. Some focal seizures can “generalize secondarily,” meaning they start in one brain region and then spread. That’s where tools like ambulatory EEG and brain imaging (MRI) come into play to clarify the diagnosis [5]. Abnormal electrical activity in nerve cells is detected by EEG and is central to the diagnosis of generalized onset seizures, which involve widespread electrical disturbances across both hemispheres of the brain.

Generalized seizures, including generalized onset seizures, can be caused by various underlying factors such as brain tumors, abnormal brain tissue, and brain damage. Some individuals develop epilepsy after brain injury, tumors, or developmental disorders. Developmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorder, are associated with an increased risk of epilepsy.

Also worth noting:

- Tonic-clonic seizures, also called grand mal seizures, are the most common presentation of idiopathic generalized epilepsy, affecting up to 86% of patients [8]. Atonic seizures are another type of generalized seizure, characterized by sudden loss of muscle control, often resulting in falls or injuries. Muscle control is often lost during generalized seizures due to abnormal electrical activity in the brain.

- Febrile seizures (or a febrile seizure) are distinct from epileptic seizures; they occur in children with high fever and are not classified as epilepsy. Febrile seizures typically have different risk factors and outcomes compared to unprovoked seizures, which are a key criterion for diagnosing epilepsy.

- Some antiseizure medications may increase the risk of birth defects, so careful management and consultation are important for women who are pregnant or planning pregnancy.

- Psychiatric comorbidities—such as anxiety, depression, and attention issues—often accompany epilepsy and must be part of the care plan, especially for teens and adults [7].

- In complex cases or when considering epilepsy surgery, evaluation and treatment at a specialized epilepsy center may be necessary to identify abnormal brain tissue and prevent future seizures.

- There is a rare but serious risk of death in epilepsy, called sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), or death on the epilepsy sudep. Proper management and medication adherence are important to reduce this risk.

Addressing epilepsy holistically leads to better quality of life, fewer hospital visits, and improved long-term outcomes.

Closing Thoughts

Generalized epilepsy is a lifelong condition, but for many people, it’s a manageable one. With the right treatment—guided by evidence, individualized to the patient, and backed by strong communication between patients, caregivers, and clinicians—seizure control is achievable.

Medications like valproic acid, lamotrigine, and levetiracetam remain the go-to choices, but optimal outcomes depend on much more than just the prescription pad. Regular follow-up, trigger avoidance, and education round out a treatment plan that can help patients live full, independent lives.

References

[1] ACEP Clinical Policies Committee, & Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Seizures (2004). Clinical policy: Critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with seizures. Annals of emergency medicine, 43(5), 605–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.01.017

[2] Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging, Lee, R. K., Burns, J., Ajam, A. A., Broder, J. S., Chakraborty, S., Chong, S. T., Kendi, A. T., Ledbetter, L. N., Liebeskind, D. S., Pannell, J. S., Pollock, J. M., Rosenow, J. M., Shaines, M. D., Shih, R. Y., Slavin, K., Utukuri, P. S., & Corey, A. S. (2020). ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Seizures and Epilepsy. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR, 17(5S), S293–S304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2020.01.037

[3] Friedman-Korn, T., Benoliel-Berman, T., Doufish, D., Shifman, T., Medvedovsky, M., & Ekstein, D. (2025). Levetiracetam-induced seizure aggravation-case series and literature review. Seizure, 129, 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2025.04.005

[4] Sullivan, J. E., & Dlugos, D. J. (2004). Idiopathic Generalized Epilepsy. Current treatment options in neurology, 6(3), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-004-0015-6

[5] Beydoun, A., & D’Souza, J. (2012). Treatment of idiopathic generalized epilepsy - a review of the evidence. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy, 13(9), 1283–1298. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656566.2012.685162

[6] Stephen, L. J., & Brodie, M. J. (2020). Pharmacological Management of the Genetic Generalised Epilepsies in Adolescents and Adults. CNS drugs, 34(2), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-020-00698-5

[7] Mayville, C., Fakhoury, T., & Abou-Khalil, B. (2000). Absence seizures with evolution into generalized tonic-clonic activity: clinical and EEG features. Epilepsia, 41(4), 391–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00178.x

[8] Asadi-Pooya, A. A., & Homayoun, M. (2020). Tonic-clonic seizures in idiopathic generalized epilepsies: Prevalence, risk factors, and outcome. Acta neurologica Scandinavica, 141(6), 445–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.13227