Gay cowboys? ‘Power of the Dog’ does not stand alone in going there

- Share via

The western tends to be macho fare, akin to the gangster movie in the genre universe. It gets dusty and brawny out there on the frontier, with all those cattle to drive and bandits to battle. It’s no accident that the movies’ exemplar of manliness, John Wayne, is also the face of the genre.

But genres are made to be subverted, and love takes many forms out on the prairie, where a certain type of machismo is expected but not always delivered. Jane Campion’s “The Power of the Dog,” which leads all movies this year with 12 Oscar nominations, is just the latest example of the queer western. These are westerns that focus on gay relationships, overtly or thematically. Their key theme is often loneliness: If the closet seems desolate in modern times, imagine what it was like on the frontier.

For the record:

12:48 p.m. March 11, 2022This article quotes a line from “Brokeback Mountain” as “Why don’t I know how to quit you?” The line is “I wish I knew how to quit you.”

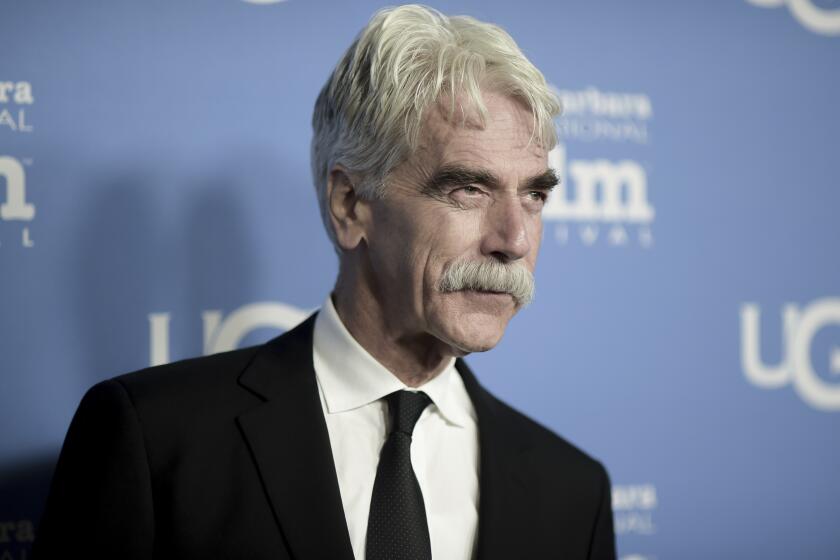

And despite Sam Elliott’s derision of the film (the actor, known largely for starring in westerns, took exception to “all these allusions to homosexuality throughout the f— movie,” on Marc Maron’s podcast this week), it’s a theme that’s been explored before. This subgenre can be quirky (1995’s “Dead Man”), heartrending (2005’s “Brokeback Mountain”) and can even put women at its fore (1954’s “Johnny Guitar”), however subtly.

Actor Sam Elliott, who has played a cowboy for most of his career, slammed Jane Campion’s revisionist take on the American West: ‘I took it personal.’

Based on Thomas Savage’s 1967 novel, “The Power of the Dog” trades in ambiguity as it explores what the New Yorker’s Brandon Taylor describes as “Jane Campion’s gothic vision of rural queerness.” The time is the 1920s. The main players are Phil (Benedict Cumberbatch), a cruel, caustic man who owns a Montana ranch with his brother, George (Jesse Plemons); and Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee), the thin, delicate son of George’s new wife, Rose (Kirsten Dunst). (All four actors are Oscar nominees.) Phil obsessively oils the saddle of the late Bronco Henry, who once saved Phil’s life by warming him up in a sleeping bag. He mocks Peter’s lisp and encourages the gay epithets hurled by his ranch hands.

The plot and characterizations deepen as Peter stumbles upon an old male nudie cache that apparently belonged to Bronco Henry, and Phil begins wooing Peter, at one point stopping just short of kissing him. But the aesthetics here are more important than the screenplay.

Campion, one of cinema’s great sensualists, captures Phil and his men with water glimmering in the sun off their nude bodies, muscles tensed, not a woman in sight. It’s the inverse of film theorist Laura Mulvey’s male gaze, in which the world is depicted from a masculine, heterosexual perspective that presents women as sexual objects. In this sense, “The Power of the Dog” has more in common with Claire Denis’ often-shirtless 1999 French Foreign Legion/battle of wills film “Beau Travail” than any western.

On a less subtle note, the queer western burst into the popular consciousness in 2005 with Ang Lee’s “Brokeback Mountain.” Here were two stars, Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal, playing Wyoming ranchers hopelessly in love with each other. The film struck a chord, winning three Oscars but losing the big one to “Crash” in a major upset. Adapted by Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana from Annie Proulx’s short story, it’s a queer western you can quote (“Why don’t I know how to quit you?”).

It’s also a tragic love story whose tragedy is rooted in a pretty traditional dilemma: Society won’t let these two people be together. Ennis (Ledger) and Jack (Gyllenhaal) both marry women who love them, but the men keep sneaking off for fishing and hunting trips together. Their rough-hewn, ranch-and-rodeo culture has no tolerance for the love that dare not speak its name, as Oscar Wilde’s lover Lord Alfred Douglas put it, though Jack pushes the issue while Ennis insists on staying in the closet. In the end, Jack is beaten to death, much like a real-life gay Wyoming man, Matthew Shepard; Jack’s family makes up a story about a roadside accident to cover the truth. Even in death, he can’t escape the closet.

The queer western needn’t always be so grave. In Jim Jarmusch’s 1995 psychedelic western “Dead Man,” a city boy named William Blake (Johnny Depp, dressed like Buster Keaton) and his Native American companion Nobody (Gary Farmer) traverse the Great Plains and come across a trio of mountain men, including Billy Bob Thornton and Iggy Pop, the latter in a dress and bonnet. They stroke William’s hair, marveling at its softness, and argue over who gets to bed him (“I saw him first!”).

There’s something refreshingly matter-of-fact about this sequence. Of course there were gay men in the Old West, the film suggests. Why wouldn’t there be? They’re every bit as natural as U.S. marshals, mustangs and prostitutes. They ultimately don’t fare well in “Dead Man,” but neither do many of those whom William and Nobody encounter. The West was a rough place, regardless of one’s sexual orientation.

Lest you think the queer western is strictly a male province, we give you “Johnny Guitar” (1954). As in “The Power of the Dog,” the queerness is largely written between the lines. But, oh, what lines. “Never seen a woman who was more of a man,” says one man of his boss, the saloon owner Vienna (Joan Crawford). “She thinks like one, acts like one and sometimes makes me feel like I’m not.” Or Vienna, commenting on the simmering passion between her adversary, ruthless baron Emma (Mercedes McCambridge), and the Dancin’ Kid (Scott Brady): “He makes her feel like a woman, and that scares her.”

Roger Ebert called “Johnny Guitar” “one of the most blatant psychosexual melodramas ever to disguise itself in that most commodious of genres, the western.” With two icons of lesbian culture in Crawford and McCambridge squaring off and making the guys, who already have names like the Dancin’ Kid, look timid by comparison, Nicholas Ray’s western, shot in the blaring tones of Trucolor, is a kind of queer western fever dream, open to interpretation. Can a movie be both erotically charged and sexless? (Bosley Crowther, writing in the New York Times, described Crawford as “sharp and romantically forbidding as a package of unwrapped razor blades”). “Johnny Guitar” is one of a kind.

Queer westerns come in all shapes and sizes and genders, and they clearly aren’t new. Perhaps this year “The Power of the Dog” will avenge “Brokeback Mountain,” which was upset at the Oscars by what is often called one of the most mediocre best picture winners in academy history. Love, as the saying goes, is love, whether it blooms in the city or the prairie, between cowboys or cowgirls. In these movies, it has no trouble speaking its name.

More to Read

Sign up for The Envelope

Get exclusive awards season news, in-depth interviews and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.