Sign up for The Envelope

Get exclusive awards season news, in-depth interviews and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Santiago Mitre’s historical drama “Argentina, 1985” tells the true story of the legal team, led by chief prosecutor Julio Strassera (Ricardo Darín), that brought a military dictatorship to justice in a civilian court. It also, indirectly, establishes the origin story of Luis Moreno Ocampo, the young deputy prosecutor who — after serving as Strassera’s courtroom partner — would later become the founding chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court.

In the film, which won the Golden Globe for non-English language motion picture, and is Oscar-nominated for international feature film, Moreno Ocampo is played by Peter Lanzani, in a memorable supporting role.

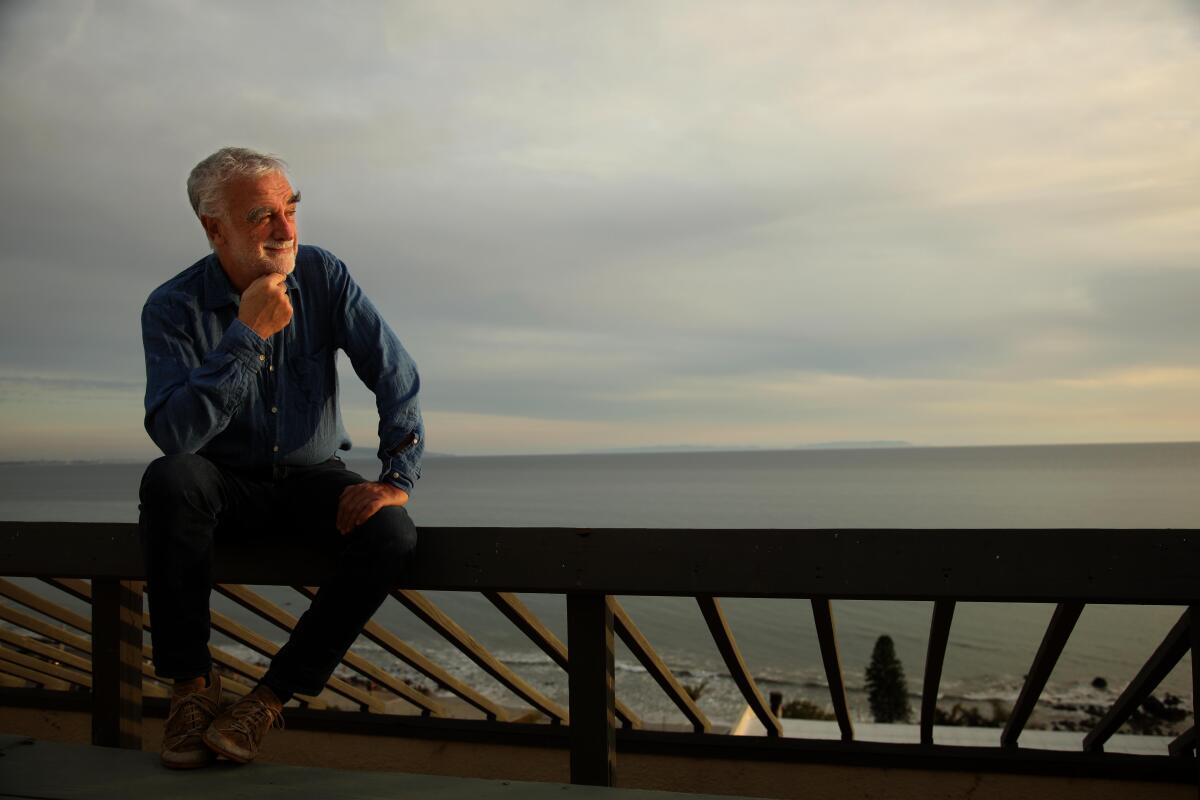

Moreno Ocampo and Lanzani had not met in person until after “Argentina, 1985” was filmed, but in a recent Zoom conversation — where the two called from Malibu and New York City, respectively — their affinity for each other was evident.

“He’s not me, but he’s a sincere Moreno Ocampo,” the real-life prosecutor says. “Peter is the age of my own son, and he is a hero to the younger generation. We have to inform them about what happened, because for people born after 1985, democracy feels normal — and it is not normal. Even in the U.S. and Brazil you have to fight for it, and Peter has helped younger generations understand that fight.”

In preparing for the role, Lanzani says he didn’t review video footage of his real-life counterpart. “We didn’t want to make a documentary about what happened,” he says. “We went into it with respect, but we made our own version of Luis, instead of just imitating the real person.”

Even so, Moreno Ocampo adds, the film is true to the historical record and his own experiences. “Santiago interviewed me for three years, and his script is really precise,” he says. “The testimonies and the closing arguments are exactly what happened in court, word for word. The creativity is all in the context.”

In an unprecedented undertaking by a democratic government, the trial of the juntas directly established the guilt of former presidents, admirals and brigadiers. During the trial, Strassera and Moreno Ocampo’s prosecution team foregrounded the testimony of victims of kidnapping, torture and murder during Argentina’s Dirty War.

The film’s texture is defined not just by the victims’ testimony, but also by the emotionally charged scenes that take place outside the courtroom. Alongside the central task of swaying a panel of judges, Moreno Ocampo faced the challenge of convincing his own mother of the military junta’s guilt.

As a performer, Lanzani was especially moved by the scene where Moreno Ocampo confronts his nationalistic mother: “That moment is very powerful, because it’s not just one character talking to his mother. It’s talking to a whole part of Argentina, and convincing our society that this trial has to happen.”

“Yes, my mother had a different mindset,” Moreno Ocampo adds. “My grandfather was a general, so she saw [former Argentinian President] Jorge Rafael Videla as her father. She went to the same church as him.” But she was eventually swayed by the testimony of one of the regime’s victims, a young teacher who was arrested while six months pregnant, then forced to give birth on the side of the road.

Moreno Ocampo says his mother’s change of heart was subtle, but decisive: “She told me, ‘I still love General Videla, but you are right. He needs to go to jail.’”

His experiences in 1985 and afterward have made Moreno Ocampo a trusted expert on questions of human rights, and the movie’s popularity has unfortunately dovetailed with a series of international threats to democracy.

“Journalists from Brazil call me all the time because of Jan. 9 and the rebellion. Journalists in Spain call me because in 1975, they transitioned to democracy without any investigation into the past. I’m going to Washington in a couple weeks because they need to understand what happened on Jan. 6 in this country. The movie is called ‘Argentina, 1985,’ but it’s not just about Argentina and not just about 1985.”

Moreno Ocampo’s storied legal career includes a decade in the Hague, and then teaching roles at Yale and Harvard, but he’s now primarily focused on issues of narrative and representation.

“I came to L.A. to teach in the USC Cinematic Arts School because I learned that you have to win your cases for the judges, but then you also have to win the communication, the narrative, the memory.”

In his class, “Shaping the World With Cinematic Arts,” Moreno Ocampo (along with co-professor Ted Braun) is focused on “the interplay between global crisis and the cinematic arts, [and] the ways in which different narratives define conflict.” His syllabus includes “The Battle of Algiers,” “Judgment at Nuremberg” and “Homeland.”

What would an Oscar win mean to the team from Argentina? Moreno Ocampo sees the campaign as an extension of his lifelong quest for justice.

“When I was first trying to promote this discussion, using the evidence I collected on the dictatorship, I wrote a book. The book sold 10,000 copies in two months. But the movie was watched by 1 million people in Argentina in a single month! And now with Amazon, it can reach 10 million people across the world, and an Oscar would add another 20 million, and that is incredibly important. The point of this Oscar promotion is to promote democracy and values and respect.”

Sign up for The Envelope

Get exclusive awards season news, in-depth interviews and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.