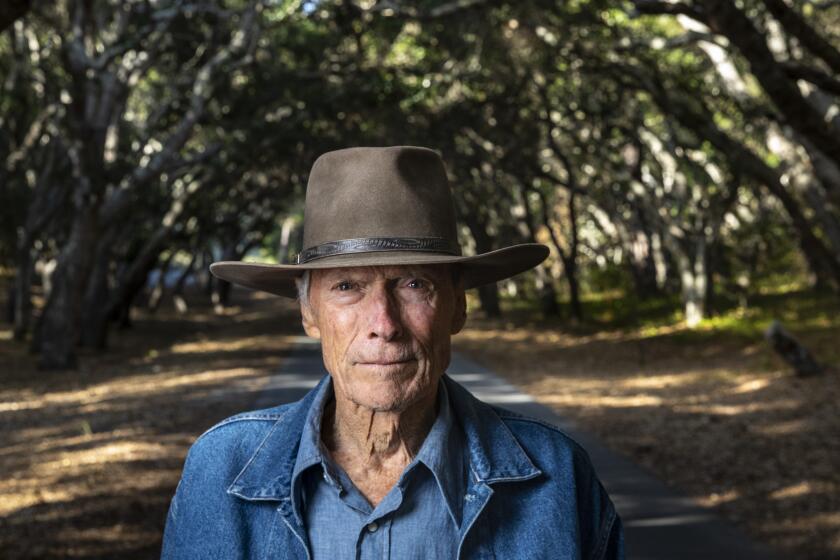

Clint Eastwood confronts his own legacy — again — in the creaky, meandering ‘Cry Macho’

- Share via

The Times is committed to reviewing theatrical film releases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because moviegoing carries risks during this time, we remind readers to follow health and safety guidelines as outlined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and local health officials.

Macho is the name of a rooster, an expert cockfighter and a plucky companion to a wayward teenager named Rafo (Eduardo Minett). Rafo, in turn, finds himself playing sidekick to Mike Milo, a faded rodeo star played with a familiar dyspeptic wince by Clint Eastwood. Making their way from Mexico to Texas in a rusty old truck sometime in 1980, the three travelers get off to a rough start, with lots of literally and figuratively ruffled feathers, before settling into a sturdy groove. Mike and Rafo, in particular, generate an affectionate rapport that implicitly rebukes the kind of aggressive male posturing summed up by the rooster’s name.

“Cry Macho,” a creaky, semi-sweet, unavoidably sentimental adaptation of a 1975 novel by N. Richard Nash, can thus be seen as Eastwood’s latest reckoning with certain wrongheaded assumptions about masculinity, and with a particular tough-guy ethos that he has both defined and subverted over his six-decade career. At this point, it would be a surprise to report that the movie was anything else. The self-critical strain in Eastwood’s work has become so pronounced of late as to run the risk of seeming repetitive. In recent years his usual motifs — the inevitability and futility of violence, the complicated and often-misunderstood nature of heroism — have tended to register with greater force and clarity than the movies themselves.

If “Cry Macho” seems too slight to bear the weight of all this thematic baggage, it nonetheless feels like a picture Eastwood had to make, and not just because the opportunity once already slipped through his fingers. (Eastwood turned down the lead in a “Cry Macho” adaptation in 1988, joining the ranks of several actors — including Robert Mitchum, Roy Scheider and Arnold Schwarzenegger — who have been eyed for the part.) He slips effortlessly into this world of cowboys and horses, dusty roads and lonely missions, though the grim fatalism that has often accompanied his forays into western territory is kept mostly at bay. The most startling violence is meted out not with guns or fists, but by Macho the rooster himself, whose various clucking, crowing performers — all 11 of them — might be collectively credited with the movie’s standout turn.

With ‘Cry Macho,’ Clint Eastwood may be the oldest American to direct and star in a major motion picture. But ask if anything has changed since his start and you get the verbal equivalent of an amused shrug.

Maybe that’s unfair. Eastwood’s human co-stars — including Minett, a Mexican television actor making his Hollywood film debut — sometimes struggle to make something emotionally credible out of the clumsy formulations of the script (credited to Nash, who died in 2000, and Nick Schenk). But Eastwood, now 91, betrays no more strain than usual. You can roll your eyes at his signature mannerisms, but taking those eyes off him is another matter. His weathered scowl and stiff, purposeful gait suit Mike Milo seamlessly, as does a tragic personal history — a rodeo career cut short by injury, a wife and child he lost years earlier — that recalls any number of Eastwood’s many soulful sufferers.

Some of those earlier roles were also written by Schenk, and “Cry Macho” echoes them in ways too deliberate to chalk up to coincidence. Like Walt Kowalski in “Gran Torino” (but with less racism), Mike must bond with a youngster whose culture proves utterly alien to him. And like Earl Stone in “The Mule” (but with less drug-cartel mayhem), Mike finds himself on a Mexican road trip that turns out to be more than he bargained for. He’s sent on this mission by his demanding former boss, Howard Polk (Dwight Yoakam, right at home), a Texas ranch owner who wants to reunite with his long-absent son, Rafo, who’s presently trapped in his mother’s allegedly abusive clutches.

Howard isn’t being entirely forthright about the situation, but those essentials are more or less accurate. You might wish they weren’t. Rafo’s mother, Leta (Chilean actor Fernanda Urrejola), turns out to be an unpersuasive collection of vampy crime-boss clichés who, despite her feigned indifference to her son’s fate, has no desire for Mike to take him across the border. Leta serves a couple of fairly obvious narrative purposes, one of which is to throw herself unsuccessfully at Mike and impress upon us the undimmed vitality of Eastwood’s sex appeal. She also commands a crew of gun-toting henchmen who take off after Mike and Rafo when they fly the coop, and who conveniently turn up whenever the proceedings need a jolt of suspense.

There isn’t all that much more to it. There are two bumbling cops who elicit some choice insults from Mike. There are the requisite bonding moments that transpire between him and Rafo, a likable kid who’s had few role models and even fewer options between his two uniquely irresponsible parents. Rafo aside, the Mexican characters in “Cry Macho” tend to be either irredeemable crooks or candidates for sainthood. Falling squarely into the latter group is a moony-eyed cantina owner named Marta (Natalia Traven) and her adorable grandchildren, who open their home to Mike and Rafo for a pleasant enough spell.

The simplicity of the story Eastwood is telling would seem to suit his unvarnished, unfussy style, though frankly, a bit more fuss — a few more takes to smooth out a wobbly performance, an extra light bulb or two in the interior shots — wouldn’t have gone awry. But “Cry Macho,” with its attractive but not indulgent landscapes (shot in New Mexico) backed by a spare, twangy Mark Mancina score, takes pains to reject anything that might smack of falsity or pretense. That’s a bit rich when you consider that the filmmaker’s much-vaunted modesty also comes with a hefty dose of self-flattery, even (or especially) when Mike calls out the preening male braggadocio that Rafo seems to idolize. “This macho thing is overrated,” he says, “just people trying to be macho and show that they’ve got grit.” For true grit, he scarcely has to add, you need look no further than Clint Eastwood himself.

‘Cry Macho’

Rating: PG-13, for language and thematic elements

Running time: 1 hour, 42 minutes

Playing: Starts Sept. 17 in general release and on HBO Max

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.