- Share via

How to encompass half a century of hip-hop? You start by acknowledging you can’t. Too many stars, too many songs, too many places, too many scandals: Hip-hop is an entire universe — a musical genre, sure, but also an attitude, a language, a business, a culture — and the thing about a universe is that it has no bounds.

Yet 50 years after hip-hop was born, we find ourselves needing to call attention to its endurance, to get our minds around the thing somehow, not because of what it was but because of what it continues to be.

Hands were wrung a few months ago when pundits realized that no rap album had made it to the top of the Billboard 200 during the first half of 2023 — a seemingly dramatic shift from 2022, when LPs by six rappers had hit No. 1 by the beginning of summer. (Lil Uzi Vert finally got there in early July with his “Pink Tape.”) But the truth is that nearly every album that topped the chart had hip-hop in its grooves, be it SZA’s “SOS,” on which the R&B singer spits rhymes with wit and dexterity, or Morgan Wallen’s “One Thing at a Time,” a country record laced with woozy trap beats.

To look for hip-hop on the charts these days — to look for it in film, in fashion, in visual art — is to find it virtually everywhere. The most important Black-pioneered art form of our time, hip-hop began as — and to some degree remains — a product of the street, accessible to anyone, even as it’s grown into a global industry that now generates billions.

Our approach to marking hip-hop’s 50th anniversary was to enumerate 50 moments that shaped the culture, one per year from 1973 to 2022. The aim of this list is to celebrate (although not with a blind eye to trouble), which is why we didn’t dwell on certain deaths or other tragedies, impactful as they were. Did we leave out key events? Fail to give every star their proper shine? No doubt. But a tribute to hip-hop that manages not to irritate somebody — well, that’s no tribute at all.

Part I

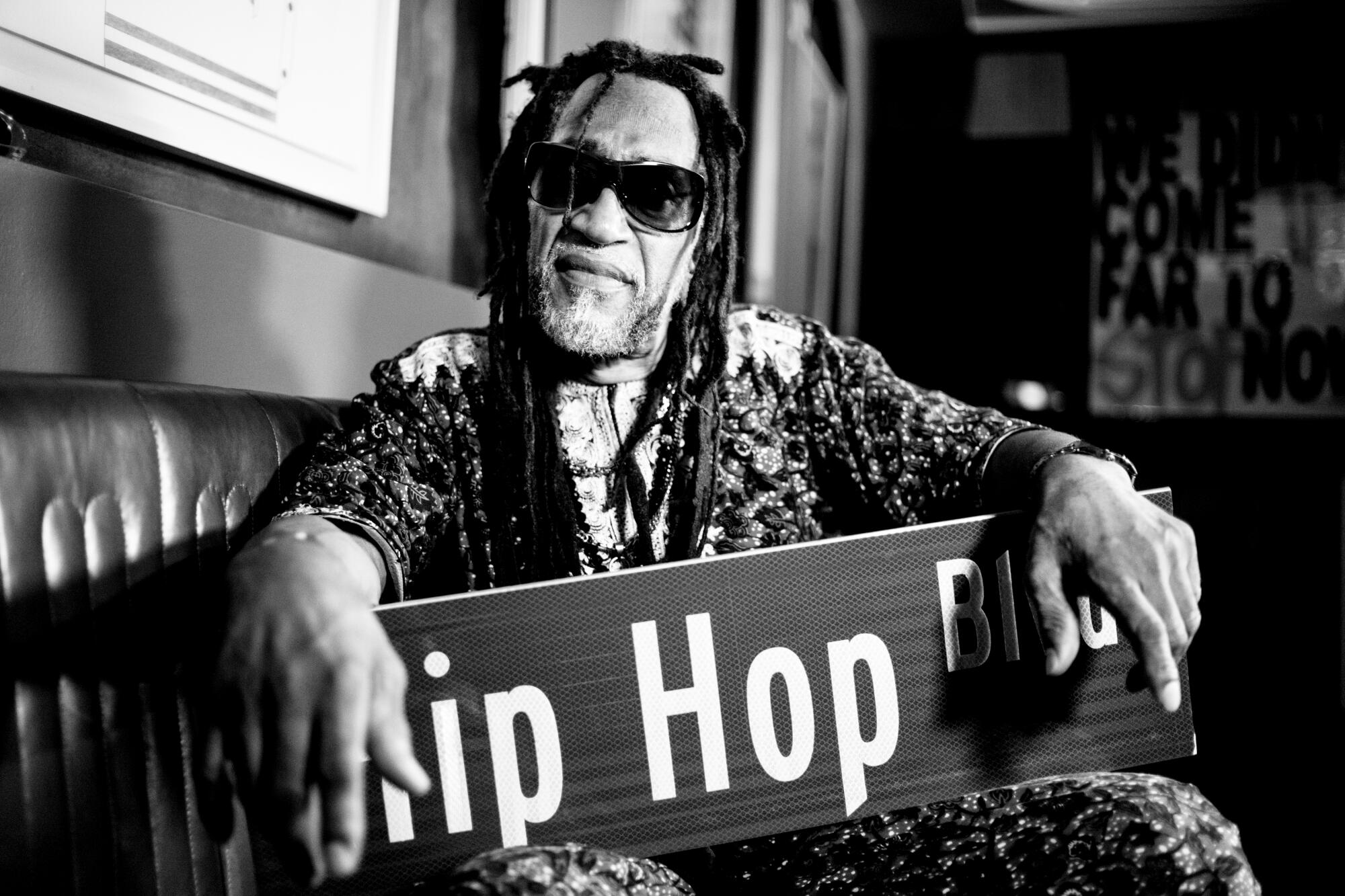

DJ Kool Herc invents hip-hop

The musical and cultural movement that would become known to the world as hip-hop began on Aug. 11, 1973, inside a recreation room at 1520 Sedgwick Ave., a 102-unit residential apartment complex in the Bronx borough of New York City. Yet when Cindy Campbell decided to throw the now legendary party credited as the big bang of rap music, making history was the last thing on her mind; she simply wanted to raise money to buy new clothes for kids for the upcoming school year. And she knew the best person to draw the type of enthusiastic crowd needed: Cindy’s 18-year-old brother, Clive “DJ Kool Herc” Campbell.

Everything about the “Back to School Jam” was hip-hop years before the term had been coined. Its hand-drawn promotional flier, which declared “A DJ Kool Herc Party,” was written in early New York-style graffiti. The 300-plus revelers that paid 50 cents (boys) and 25 cents (girls) to get inside were treated to a playlist of future hip-hop-DJ staples that included “It’s Just Begun” by the Jimmy Castor Bunch and classic cuts from James Brown, the Isley Brothers and the Incredible Bongo Band. And Herc, who got the nickname “Hercules” because of his massive, muscle-bound 6-foot 5-inch frame, unveiled a new turntable technique known as “the merry go ‘round,” in which he would use two versions of the same record to extend the song’s meatiest section, igniting dancers he dubbed the break boys (B-boys) into a frenzy.

After the party, Herc’s stature only grew. He became known for his mammoth speakers, a six-foot tower-of-sound he called the “Herculoids,” which frequently overpowered opposing DJs in the parks and at the clubs. Soon, other pioneers like Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa would follow his lead. In November, DJ Kool Herc, now 68, will finally be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame for his foundational contribution to popular culture. — Keith Murphy

James Brown releases “Funky President (People It’s Bad)”

As the most sampled artist in rap history, Brown laid the break beat foundation for hip-hop. Even in ’74, when critics questioned whether the Godfather of Soul still had it, he delivered the effortless “Funky President (People It’s Bad),” which ranks among his all-time most mined tracks. Elements of the strutting workout’s elastic drums, soul-power vocals and slinky guitars have been lifted by the likes of Eric B. & Rakim (“Eric B. Is President”), Salt-N-Pepa (“Shake Your Thang”), Public Enemy (“Fight the Power”) and Kanye West (“Clique”). — K.M.

Grand Wizzard Theodore invents scratching

Like just about everything else in hip-hop, the technique of scratching records is an art form born of limitation. In 1975 (as best remembered), a tween DJ named Theodore Livingstone — called Grand Wizzard Theodore for his precocious talent — was practicing his craft at his Bronx home. He had “Bongo Rock” from the Incredible Bongo Band cued up when his mom yelled at him to turn it down, and he accidentally nudged the record, making an audible rip in the playback. It was wrong but kind of interesting.

Livingstone soon figured out that with a bit of manual deftness and a deep feel for his records, he could use that “scratching” sound as percussion. With even more practice, he learned to jump between turntables and splice moments of songs together.

This novel technique wowed his mentor Grandmaster Flash, and it soon became a foundational element of hip-hop. Under the mantle of Grand Wizard Theodore & the Fantastic 5, Livingstone released the stellar 1980 single “Can I Get a Soul Clap,” and his flamboyant stage presence and record flips earned him a slot in the landmark rap film “Wild Style.”

Livingstone also perfected the “needle drop,” where a DJ begins a track by lowering the stylus from dead silence, rather than cueing a song up in advance in his headphones. But it was scratching that became as important to hip-hop as the distortion pedal is to rock ’n’ roll — a mistake so profoundly transformative that it became an essential tool. — August Brown

Lee Quiñones tags a 10-car subway train

Hip-hop, as a nascent subculture, encompassed many art forms, graffiti being one of the most visible and divisive. With a spray can in the right hands, it was a thrilling reclamation of urban space, a defiant declaration that you exist here, right now.

No single piece of graffiti art was more important than Quiñones’ daredevil project on a New York City subway in 1976. The Puerto Rico-born Quiñones and the Fabulous Five crew were a respected underground street-art team. But his audacious plan to tag up an entire 10-car subway train — widely acknowledged as one of the first to ever try it — would make his career as a hip-hop folk hero. Mickey Mouse, a Christmas tableau, a desert landscape — a utilitarian piece of public infrastructure suddenly became a global symbol of a new art form.

Quiñones now has work at the Whitney Museum and designed the lobby for New York’s Hotel Indigo. But back in ’76, even the MTA workers knew they’d just seen some kind of audacious history being made. “We were hanging out the sides and the windows going, ‘Yaah! Fabulous Five!’” Quiñones told an interviewer in 1982. “I heard the conductor going, ‘Who the hell pulled that?’ Then I saw all the Fab Five jumping out of the train shouting, “Yaah, take pictures!’ There was only one guy in that station, and he was looking at us. And I said, ‘How do you think about it?’ And he said, ‘Incredible, man, incredible!’” — A.B.

Afrika Bambaataa hosts the first Zulu Nation party

When Bambaataa began hosting his legendary Zulu Nation block parties in 1977, the South Bronx, N.Y., native and Black Spades warlord intended the gatherings to provide a peaceful environment for fellow former gang members looking for a positive outlet. Yet the first jam thrown by the pioneering DJ and activist would have a far more enduring impact: Bambaataa (born Lance Taylor) was the first to envision rap music as a cultural movement, during a turbulent year in which New York City was crippled by a summer blackout and fires burned throughout the slums of the South Bronx.

Bambaataa and his crew preached the four elements of hip-hop that would soon define the burgeoning scene: deejaying, B-boy/girl dancing, emceeing and graffiti painting. But it was his catholic taste in music that melted minds: Alongside favorites from James Brown, Sly and the Family Stone and the Incredible Bongo Band, Bambaataa’s massive vinyl arsenal included the Rolling Stones, the Yellow Magic Orchestra and most notably German morotik kings Kraftwerk, whose futuristic ’77 single “Trans Europe Express” became a break-dancing anthem.

By 1982, the groundbreaking “Planet Rock,” which sampled “Trans Europe Express,” had made Bambattaa and his Soulsonic Force a gold-selling act. He waved the flag for the Zulu Nation until he was removed from leadership in 2016 following multiple allegations of sexual abuse dating back decades. Since parting ways with Bambaataa, the Universal Zulu Nation has continued to push forward its message of hip-hop unity. — K.M.

Uncle Jamm’s Army throw ragers across L.A.

Brothers Gid, Tony and Greg Martin stood in a Harbor City backyard, plotting ways to earn some money. Their plan? Organize and promote dance parties across L.A. After teaming up with record-store owner and master DJ Rodger Clayton, the crew drew up posters and hit the town, duking it out with the likes of the World Class Wreckin’ Cru and Ultra Wave for control of the city’s dance floors. They called their collective Uncle Jamm’s Army, after the Funkadelic album “Uncle Jam Wants You.”

Before long, Uncle Jamm’s Army had sold out the Santa Monica Convention Center, then the Hollywood Palladium and finally, the L.A. Sports Arena. Membership in the Army was fluid: Participants would go on to include Ice-T, DJ Pooh and DJ Egyptian Lover, and the crew graduated from spinning other artist’s records to making their own, driving the growth of electro music and building a foundation for early L.A. hip-hop. — Kenan Draughorne

“I said a hip-hop, the hippie, the hippie / to the hip, hip-hop and you don’t stop...”

On Oct. 20, 1979, high-school friends Angela Brown, Cheryl Cook and Gwendolyn Chisolm found themselves in a make-or-break audition. Like many adventurous teens at that culture-shifting moment in time, the Columbia, S.C., natives were enamored by a new musical art form that had defiantly risen out of New York’s impoverished South Bronx: hip-hop.

Yet the record that inspired the cheerleaders to create their own rap group called the Sequence, which would become the first female and first Southern rap act to sign a label deal, did not come out of the hallowed Boogie Down Bronx turf of hip-hop originators DJ Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash. “Rapper’s Delight,” the game-changing debut by the Sugarhill Gang, was produced out of Englewood, N.J., and featured unlikely rhyme pioneers Michael “Wonder Mike” Wright, Henry “Big Bank Hank” Jackson and Guy “Master Gee” O’Brien. “The Sugarhill Gang resonated with us,” says Brown, better known these days as Grammy-nominated R&B singer Angie Stone.

Roland releases TR-808 drum machine

When the Roland TR-808 was introduced to the buying public, the electronic percussive kit was deemed a commercial and critical flop. Keyboard magazine summed up the overall reaction to the Ikutaro Kakehashi design, describing its hi-hats as sounding like “marching anteaters.” Yet none of that mattered to the burgeoning hip-hop scene as the new technology presented the perfect vehicle for the rebellious forward-looking movement. Since anchoring Afrika Bambaataa & the Soulsonic Force’s landmark “Planet Rock” (1982), the 808 has become the genre’s go-to drum machine and still can be heard on some of today’s biggest Southern rap productions. — K.M.

Blondie’s “Rapture” becomes the first rap video on MTV

What a telling irony that the first rap video ever played on a nascent MTV came courtesy of Blondie, a band of white downtown New York art-rockers. Hip-hop has long posed thorny questions about how race and music interact and who has the right to profit from the culture. In the early ’80s, though, it was enmeshed in New York’s avant-garde, with ambitious artists from all genres and backgrounds taking notice of its musical promise. That included Blondie, whose single “Rapture” — a post-disco New Wave staple — incorporated some of the vocal cadences and techniques of hip-hop. Their bona fides were genuine — they were pals with Fab 5 Freddy, one of hip-hop’s crucial pioneers. He introduced the band to the bustling Bronx scene and appeared in the song’s video alongside artist Jean-Michel Basquiat and graffiti king Lee Quiñones.

“Rapture’s” success foretold the genre’s potential on MTV, even as network execs more or less maintained a whites-only programming policy until CBS Records strong-armed them into airing Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean” video in 1983. Eventually, Fab 5 Freddy became an MTV star in his own right; he became the inaugural host of the show “Yo! MTV Raps” in 1988. — A.B.

Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five deliver “The Message”

“The Message,” considered by many to be the greatest hip-hop song ever recorded, nearly didn’t happen.

In early 1982, Sugar Hill Records head Sylvia Robinson was looking to break out of the “party rhymes” formula that had come to define her label since the 1979 release of the Sugarhill Gang’s debut “Rapper’s Delight.” She envisioned an unflinching rap composition dealing with the real-life struggles of life in the ‘hood. Sugar Hill Records percussionist “Duke Bootee” Fletcher was ready to take on the challenge.

Although he wasn’t an MC, Fletcher wrote poetry. At his home in Elizabeth, N.J., he penned the lyrics to a song he called “The Jungle,” describing the rough social and economic conditions of the Black ghetto. “I lived across from a park, and I would hear a bottle get broken every once in a while, and I started with that ‘broken glass everywhere,’” Fletcher recalled of the opening line of “The Message.” He quickly teamed up with Sugar Hill arranger and producer Jiggs Chase, who created the track’s signature groove, and the pair unveiled their collaboration to a thoroughly impressed Robinson.

Yet the talent on her streetwise imprint did not share her enthusiasm. They bristled at the idea that their young fans would be interested in hearing a serious, socially conscious statement. Rapper Spoonie Gee turned it down. The Sugarhill Gang’s Master Gee threw the tape away. “No one wanted to do the song,” said Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s Melle Mel. While Robinson eventually persuaded the group to release “The Message,” Melle Mel’s iconic final verse (“A child is born with no state of mind / blind to the ways of mankind…”) was the only contribution to the song made by a member of the group. (Duke Bootee is the other featured rapper on the track.) Prodded by the label, the group filmed a now-seminal video for the gritty track. Eleven days later, the song went gold.

“The Message” gave birth to reality rap, marking a pivotal moment in the evolution of popular music. This year, it was selected by the Library of Congress among a first group of 50 important American recordings. Not bad for a record no one wanted. — K.M.

L.A.’s KDAY invents rap radio

A week after moving to Los Angeles from Houston in 1983, Greg Mack wandered into Ameraycan Recording Studios in North Hollywood, ready to shake some hands at an industry party. Recently hired as the music director for KDAY-AM (1580), Mack, 23, was there on a direct invitation from singer Ray Parker Jr., who owned the studio, and found himself talking with Parker and famed soulman Barry White soon after he walked in.

“I still had that Texas twang, and as I was talking, Barry just started laughing,” Mack said. “I was like ‘What?’ and he said, ‘Man, I’m not laughing at you, I’m just feeling you. You’re like a breath of fresh air.’

“‘You’re gonna do just fine,’” Mack recalled White telling him. “‘Control this city, don’t let this city control you.’”

White’s words were a striking premonition. When Mack came aboard as music director, KDAY, which first signed on the air in 1948, ranked fifth out of five urban-format radio stations in Los Angeles.

“They had a younger demographic,” said Lonzo Williams, promoter of the L.A. electro group World Class Wrecking Cru and owner of the Eve After Dark nightclub in Compton. “They played R&B and funk... artists like Tom Browne, Cameo, Frankie Smith’s ‘Double Dutch Bus.’”

Within 90 days of Mack’s hiring, however, KDAY leapfrogged all the way to No. 2, outranked only by the sole urban-format FM station in the city, KACE.

Mack’s secret? The music director rolled down his window on a drive through South-Central and heard rap music: Run-D.M.C., Kurtis Blow and the Sugarhill Gang, to be specific.

The Roxanne wars

Hip-hop’s earliest recorded rap battle almost didn’t happen.

Before UTFO released the 1984 phenomenon “Roxanne, Roxanne,” the Brooklyn foursome had planned to make the track the B-side to its electro club jam “Hanging Out.” But when the group’s manager gave the 12” to New York radio station Kiss-FM’s Kool DJ Red Alert, the taste-making DJ had other ideas.

“[Red] said, ‘No, I’m going to play the B side,’” UTFO’s Fred “Doctor Ice” Reeves said in a 2017 interview, thus catapulting the group — Reeves, Shaun “Kangol Kid” Fequiere, Jeffrey “Educated Rapper” Campbell and Maurice “Mix Master Ice” Bailey — into music history, and opening the door for 14-year-old Lolita Shante Gooden to make her own. “It turned out to be so huge nobody even knows there was an A side.”

Produced by R&B band Full Force, “Roxanne, Roxanne” — with its entertaining tale of an “all stuck up,” around-the-way fly-girl who rejects the competing advances of UTFO — captured the imagination of young hip-hoppers nationwide, cracking the top 10 of the Billboard R&B chart.

Yet the story of “Roxanne, Roxanne” took on a life of its own when Gooden, a.k.a. Roxanne Shanté, jumped in. After UTFO canceled an appearance at a New York concert, one of the gig’s organizers, future Juice Crew producer Marley Marl, persuaded the young Queensbridge Houses battle rapper to record “Roxanne’s Revenge,” an at-times shockingly profane response targeting the group.

Within weeks of its debut, Shante’s “Roxanne’s Revenge” had sold 250,000 copies in New York City alone. “Getting me to go into the studio was a difficult practice,” Shanté admitted in 2019. “I wasn’t a studio rat. When I recorded ‘Roxanne’s Revenge,’ I was literally doing laundry.” After finishing up her chores, Shanté got down to business: “He ain’t really cute, and he ain’t great / He don’t even know how to operate,” she fired away at Doctor Ice and UTFO.

UTFO and Full Force returned serve with “The Real Roxanne,” featuring newcomer Elease Jack, who would later be replaced by the model-esque Adelaida Martinez. Brooklyn’s Sparky D jumped in with “Sparky’s Turn (Roxanne, You’re Through).” By the following year, a flood of Roxanne records had hit the market, including “The Parents of Roxanne,” “I’m Lil Roxanne,” “Roxy: Roxanne’s Sister,” “Roxanne’s a Man (The Untold Story — Final Chapter)” and “The Final Word — No More Roxanne (Please).”

By the time the dust had settled, an estimated 100 Roxanne novelty songs had been released in an attempt to cash in on the craze. “It was flattering and a few of them were funny,” Kangol Kid said in 2019, “but I was trying to be great like Grandmaster Flash & the Furious 5, the Cold Crush Brothers and Run-D.M.C. While I appreciate the fact that I was part of something that people wanted to emulate, it was annoying that these people couldn’t be original.”

Yet Fequiere may have been selling UTFO’s impact short. Although a reunion never got off the ground — Campbell died in 2017 and Fequiere in 2021 — the song was a gateway for rap’s soon-coming commercial coronation. Roxanne won. — K.M.

Part II

Luther Campbell plants a flag for the South

Although Southern rap is a defining sound of the modern era, it’s often overlooked in the story of the first decades of the genre. Atlanta would become the region’s rap capital, with Memphis, Tenn., and New Orleans and Virginia making era-defining impacts too. But it is Florida, that beautiful and cursed state, where Luther Campbell of 2 Live Crew planted his flag for Luke Skyywalker Records, one of the first Southern rap labels to make a national impact. 2 Live Crew — his group that made records so lascivious they re-shaped American legal theory about free speech — would not have been possible without the independent infrastructure he established with his Miami label (later changed to Luke Records). Campbell set a precedent for Southern rappers not waiting around for the coasts to notice them — they’d cut records on their own terms, to their own tastes, making the music all the more potent for it. — A.B.

Run-D.M.C. gets paid by Adidas

By the time Run-D.M.C. stepped onstage at Madison Square Garden in New York City on July 19, 1986, Joseph “Run” Simmons, Darryl “D.M.C.” McDaniels and Jason “Jam Master Jay” Mizell were already well-versed in making history.

The trio’s 1984 self-titled debut made the group the first hip-hop act to go gold. With the release of its sophomore album, “King of Rock” (1985), it hit another hip-hop milestone, selling more than 1 million copies while becoming the first rappers to receive video airplay on MTV. And a year later, the Kings of Queens once again etched their names in the record books as the first rap act to go multiplatinum with “Raising Hell.”

While Run-D.M.C. was leading hip-hop to mainstream glory, Adidas was searching for a Hail Mary. For decades, the German footwear and sporting goods powerhouse had dominated the international market. However, by the mid-’80s, the company was losing significant market share in America to Nike and its high-flying flagship basketball phenomenon Michael Jordan, as well as to Reebok, a major player in the aerobics explosion. Lyor Cohen, Run-D.M.C.’s road manager, invited Adidas executive Angelo Anastasio to the MSG concert to show off the group’s untapped potential as style trendsetters

During the sold-out, 45-date Raising Hell arena tour, the power of Run-D.M.C. was on full display. Many fans in attendance sported the group’s trademark look: tracksuits, dookie rope gold chains, black Fedora hats and, most conspicuously, the classic three-stripe Adidas sneaker, oftentimes with no laces, immortalized on the group’s 1986 single “My Adidas.”

“Now me and my Adidas do the illest things / We like to stomp out pimps with diamond rings / We slay all suckers who perpetrate / And lay down law from state to state,” D.M.C. and Run proclaimed over the sparse Rick Rubin beat propelled by the monster cutting and scratching of Jam Master Jay.

“The record had already been out for around three months,” McDaniel recalled in an interview of the group’s pivotal Madison Square Garden performance of “My Adidas,” “and when Run said: ‘Take your trainer off and hold it up,’ I held up my sneaker up to 20,000 people in the audience, and they did the same. It was crazy.”

Anastasio was so impressed that he signed Run-D.M.C. to a $1.5-million deal with Adidas to push the group’s own signature shoe, a first not just for a rap act but also for any musician. Adidas’ timing couldn’t have been more perfect: Weeks before the Madison Square Garden concert, Run-D.M.C. had released its cover of Aerosmith’s 1975 rock classic “Walk This Way,” featuring the band’s Steven Tyler and Joe Perry, accompanied by a video that was quickly seared into the hearts and minds of young, MTV-besotted America: An Adidas-clad Run-D.M.C. are in a room practicing, drowned out by Aerosmith’s screaming guitar theatrics next door. Each group bangs on the wall to complain about the noise. Finally the wall collapses, and with it, the divide between hip-hop and rock ’n’ roll.

Run-D.M.C.’s “Walk This Way” raced to No. 4 on the Billboard Hot 100, reviving the waning career of Aerosmith. Meanwhile, the Superstar, Run-D.M.C.’s first Adidas shoe, would sell a half-million pairs that same year. Soon, the group had its own Adidas shoe line — the high-top Eldorado and Fleetwood and the low-top Brougham, named after their favorite cars, and the Ultrastar, which featured an elasticized tongue so buyers could wear them laceless like their heroes — along with Run-D.M.C. sweatshirts and leather tracksuits.

Endorsement deals in hip-hop have since become par for the course. But when Kanye West and Adidas reached multibillion heights with their Yeezy shoe empire, they stood on the shoulders of Run-D.M.C. — K.M.

Def Jam goes on tour

At the time, the 1987 Def Jam tour was the most ambitious hip-hop trek ever produced, with a lineup that included soon-to-be double-platinum headliner LL Cool J, Whodini, Eric B. & Rakim, DJ Jazzy Jeff & the Fresh Prince, Doug E. Fresh, an up-and-coming Public Enemy and more. The arena gigs averaged 10,000 to 12,000 seats and would gross $6.5 million (more than $17 million adjusted for inflation). Yet the all-star tour faced strong headwinds: The year before, Run-D.M.C.’s Raising Hell arena tour had packed them in, but the shows also generated negative (and racially biased) headlines because of a few violent incidents. The Def Jam tour proved the doomsayers wrong. — K.M.

Public Enemy and N.W.A bring fury to rap

The genesis of the most pivotal year in hip-hop began in the summer of 1987. Hank Shocklee was listening to his car radio on the way to a Long Island movie theater with his family when Eric B. & Rakim’s “I Know You Got Soul” suddenly jumped out of the speakers. By then, the iconic duo’s platinum debut, “Paid in Full,” had seemingly changed the direction of rap overnight.

Shocklee, a founding member of Public Enemy’s innovative production team the Bomb Squad, sat gobsmacked. He frantically called PE’s lead orator, Chuck D, who was likewise overwhelmed by what he had just heard.

“‘I Know You Got Soul’ stopped time,” Shocklee recalls. “When that record came out, every other song was quiet. Me and Chuck got mad because ‘I Know You Got Soul’ was too good [laughs]. Now we had to do something to top that.”

A teenage Notorious B.I.G. freestyles on a Brooklyn corner

A 17-year-old stands on a street corner in Brooklyn, N.Y.’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. He’s in front of a grocery store, surrounded by buddies and locals, holding a mic with a beat behind him. The kid’s freestyling with preternatural poise and style, never missing a syllable, roasting a dude in the circle who knows he’s been beaten.

You can hear the seeds of an instrument taking shape, a voice coming into its own. The kid looks confident, but still maybe cautious about his obvious talent, as passers-by turn around to watch him perform.

The kid is Christopher Wallace, and soon enough, he would become Biggie Smalls, a.k.a. the Notorious B.I.G., one of the most important, beloved and tragic artists of his time. But for this one minute in 1989, he’s just a teenager having a blast in his neighborhood, fully alive to the possibility of hip-hop and his place in it. — A.B.

“Check out the hook while my DJ revolves it”: Hip-hop goes pop

Think of it as hip-hop’s inevitable Elvis Presley moment: Thirty-four years after the King of Rock ’n’ Roll scored a No. 1 pop hit with his version of Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog,” another pompadoured white man took another Black art form to new commercial heights when Vanilla Ice’s “Ice Ice Baby” became the first rap song to top Billboard’s Hot 100.

Built on a prominent sample of the bass line from “Under Pressure” by Queen and David Bowie — though Vanilla Ice initially claimed that a “little-bitty change” to the riff made it his own — “Ice Ice Baby” brought international stardom to the rapper and dancer born Robert Van Winkle, whose breakout single drove sales of his 1990 LP, “To the Extreme,” to seven-times-platinum status.

To listen now to “Ice Ice Baby” is to re-encounter its obvious charms: the sticky rhymes about Lamborghinis and less-than-bikinis; the title chant borrowed from a storied African American fraternity; that hypnotic bass line, so easy to check out while his DJ revolves it. Yet to hear the song today is also, of course, to recognize the market advantage of Vanilla Ice’s whiteness, even if the rapper himself seemed uncomfortable with that idea decades ago. “My being white had something to do with it, but not as much as they say it does,” he told the New York Times in 1991 of his ascent.

As with those of Elvis, Vanilla Ice’s achievement extended gains made before him by Black artists finding more limited crossover success. In 1988, Tone Loc peaked at No. 2 on the Hot 100 with the Van Halen-sampling “Wild Thing,” which the song’s co-producer Mike Ross notes broke out first on L.A.’s alt-rock KROQ-FM (106.7). The next year, Young MC made it to No. 7 with “Bust a Move,” which, like “Wild Thing,” came out on Ross’ Delicious Vinyl label. Digital Underground went to No. 11 in 1990 with the comic “The Humpty Dance.” And then there was that year’s “U Can’t Touch This” by MC Hammer, who took Vanilla Ice on the road as an opening act before the two had a falling-out.

The smash “U Can’t Touch This” topped out at a surprisingly low No. 8 on the Hot 100, due in large part to the decision by Hammer’s label not to release the song as a cassette single in an effort to get consumers to buy his album — which they did by the millions. Nevertheless, that marketing gambit gave Vanilla Ice bragging rights in regards to “Ice Ice Baby’s” historic singles-chart position.

And brag he did: “At his pinnacle, I would say there was a lot of arrogance,” says Michael Mena, a former exec at Vanilla Ice’s label, SBK Records, who remembers a photo opp with the rapper and the label co-founder Martin Bandier — the “B” in SBK — and Bandier’s daughter.

“Afterwards, he said to Marty, ‘Hi, Dad,’” Mena recalls with a laugh. “I was like, ‘Boy, I don’t know if Marty’s gonna like that.’” (Vanilla Ice didn’t respond to a request from The Times for comment.)

The rapper made the most of his instant celebrity, dating Madonna, who put him in her much-discussed “Sex” book, and appearing in 1991’s big-screen “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze.” Later, he said “Ice Ice Baby” didn’t represent the real him. “They made me look like Evel Knievel,” he told Spin magazine in 1994. “Some f— teen idol or somethin’. And that just ain’t me.” He remade the song as a tortured nü-metal screed on 1998’s “Hard to Swallow.”

If its legacy is complicated, though, “Ice Ice Baby” undeniably opened the door through which Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg and 2Pac entered the mainstream to become pop superstars. Abbey Konowitch, a music-industry veteran who programmed MTV in the late ’80s and early ’90s, compares hearing Dre’s “Nuthin’ but a ‘G’ Thang” to the first time he heard “Sweet Child o’ Mine,” the gritty-sexy Guns N’ Roses hit that made earlier hair-metal songs by Bon Jovi and Poison seem downright wholesome. Like those airbrushed tunes did for hard rock, Vanilla Ice’s bubblegum-rap sensation made hip-hop “more accessible to the suburban audience,” Konowitch says. — Mikael Wood

Ice-T becomes the first big-time rapper-actor with “New Jack City”

Rappers had been in movies before 1991.

Fab 5 Freddy played a version of himself in 1983’s semi-documentary “Wild Style.” Melle Mel rocked a party wearing a zebra-print vest in 1984’s “Beat Street.” And who can forget Run-D.M.C.’s quest for vigilante justice in 1988’s “Tougher Than Leather”?

But not until Ice-T appeared in “New Jack City” had an MC ever taken on a prominent dramatic role in a major Hollywood production.

Dr. Dre releases “The Chronic”

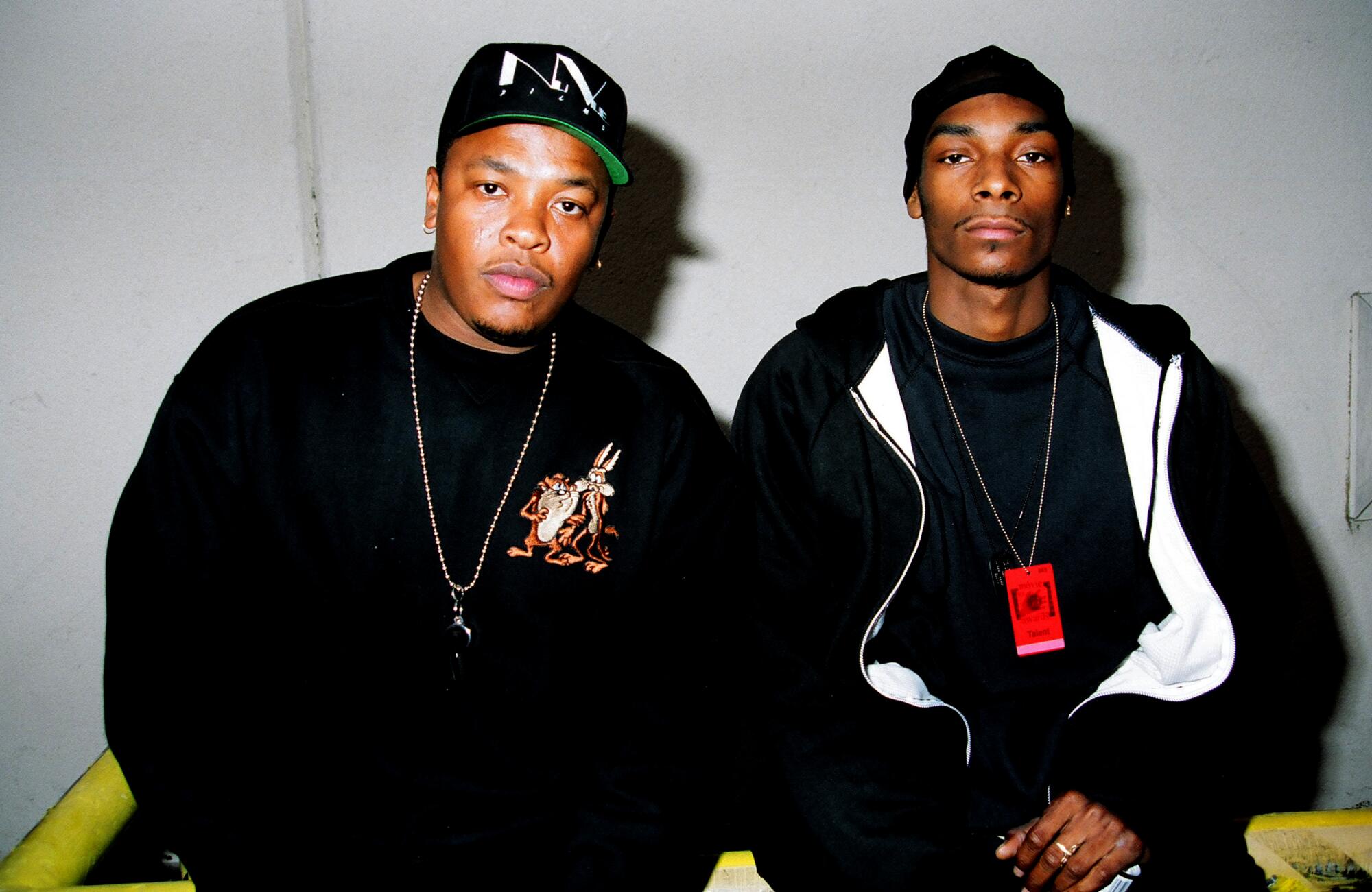

Dr. Dre looms over L.A. hip-hop culture today like a mountain range — something that’s always been there, defining the landscape. Rap’s first billionaire, mentor to hall-of-famers from Snoop Dogg to Eminem, headphones magnate, Super Bowl history-maker — the modern music industry would be unrecognizable without his contributions.

But in 1992, he was still a young producer with something to prove. The architect of N.W.A’s sound — what would become the slow-rolling, laconic style of G-Funk — was not the face of that incendiary group. But he emerged as a solo artist signed to an alluringly dangerous new label, Death Row Records.

First came “Deep Cover,” recorded for the soundtrack of the gangsta-noir film of the same name. Dre’s bracing solo debut took the cop-taunting menace of N.W.A’s “F— tha Police” into even steelier, operatic depths, and introduced one of his young charges, a lean and stylish Long Beach MC named Calvin Broadus, rapping under the name Snoop Doggy Dogg.

The two would reunite later that year on “The Chronic,” Dre’s first solo LP, an instant classic across the Southland. It remains a standout document of a time and place in music — the era when “West Coast” became both a fully articulated style and a global commercial force. The mix of P-Funk samples, nimbly melodic synth lines and hyper-violent lyricism defined a region and captivated the country. Can you imagine life in L.A. without “Nuthin’ but a ‘G’ Thang” or “Let Me Ride?” We won’t even try.

“The Chronic” peaked at No. 3 on the Billboard 200, spending eight months in the Top 10 and introducing soon-to-be-stars Nate Dogg and Warren G. Famously, it turned Snoop Dogg into a must-watch MC who would soon release the Dre-produced “Doggystyle,” another L.A. classic.

Dre’s career as a producer and executive would soon eclipse even this era, as he ushered Tupac Shakur to superstardom and left the troubled Death Row to found Aftermath Entertainment, where he discovered Eminem and 50 Cent. He’d go on to co-found Beats by Dre with Interscope boss Jimmy Iovine; the two would sell the company to Apple for $3 billion in 2014. But in 1992, there was no one closer to the beating heart (and writhing synth) of a new dawn in popular music. Nothing would be the same in the aftermath. — A.B.

Cash Money Records recruits Mannie Fresh

Before Fresh joined the fledgling Cash Money label, eventually overseeing production on records that sold more than 23 million copies, he was the major draw at the popular New Orleans spot Club Rumors. While other deejays would spin MC T. Tucker’s and DJ Irv’s foundational 1992 single “Where Dey At?” to get the crowd hyped, Fresh augmented the local favorite credited with being the city’s first bounce record with R&B and church-music samples. Not only were clubgoers enthralled, so were brothers Bryan “Baby” Williams and Ronald “Slim” Williams, who in ’93 recruited him to be Cash Money’s in-house studio visionary. Five years later, the move had paid off as Fresh kicked off a blistering run with Juvenile’s quadruple platinum “400 Degreez.” Since then, Fresh has found commercial acclaim with Birdman as one half of the platinum duo Big Tymers and has manned the boards for everyone from Lil Wayne to T.I. — K.M.

The Source gives Nas’ “Illmatic” 5 mics

When Nas was 12, he “went to hell for snuffing Jesus” — at least, that’s what he claimed on Main Source’s “Live at the Barbecue,” the first verse of his that the world would ever hear. With that song, along with a feature on MC Serch’s “Back to the Grill” and his own debut single “Halftime,” Nas had the world at his feet. How high were expectations for his debut album? Influential rap magazine the Source proclaimed him “the second coming.”

But Nas didn’t just clear the bar; he delivered what many still consider to be hip-hop’s finest album in “Illmatic.” When the Source awarded it with its highest rating — the hallowed “5 mic” review — it sent shock waves; only six albums at the time had ever received the honor, and it was exceedingly rare for it to go to a new artist.

In just over 500 words, Source intern Minya Oh wrote the album into history, raving over Nas’ lyrical ability and the elite production from DJ Premier, Large Professor, Pete Rock, Q-Tip and L.E.S. “The bottom line is this: even if the album doesn’t speak to you on that personal level, the music itself is still well worth the money,” Oh concluded. “If you can’t at least appreciate the value of Nas’ poetical realism, then you best get yourself up out of hip-hop.” — K.D.

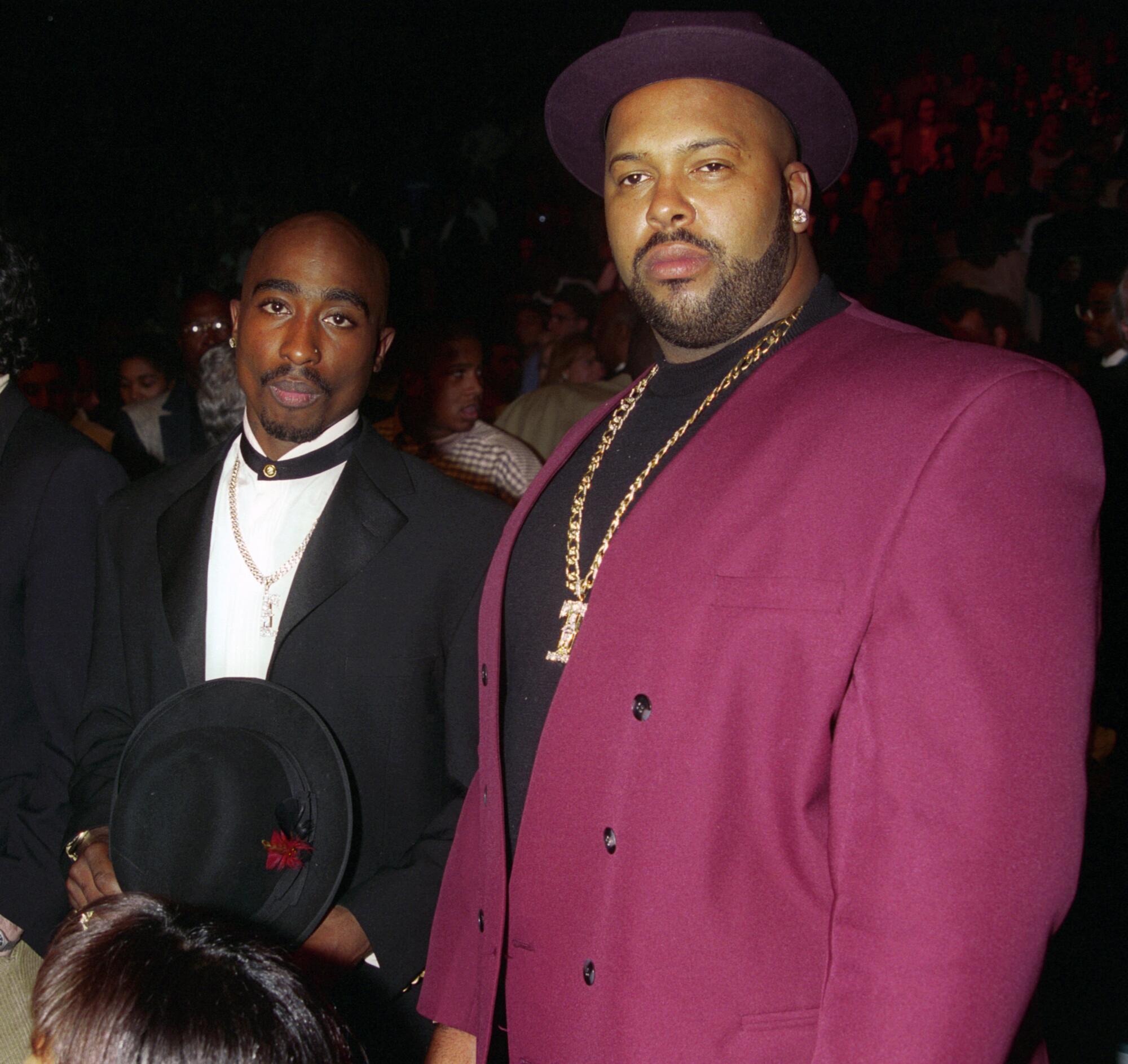

“Come to Death Row”

On Aug 3, 1995, Marion “Suge” Knight, then the chief executive of Death Row Records, used one of hip-hop’s biggest celebrations as an opportunity to sow discord.

At the second Source Awards, at Madison Square Garden’s Paramount Theater in New York City, Knight closed his acceptance speech for soundtrack of the year with a very public insult and an invitation.

“Any artist out there that want to be an artist, stay a star and don’t want to have to worry about the executive producer being all in the videos, all on the records, dancing — come to Death Row.”

The barb was aimed at Bad Boy Records Chief Executive Sean “Diddy” Combs and his love of the spotlight. Bad Boy, based in New York, had emerged as the music industry’s new sensation due in large part to the Notorious B.I.G. and his 1994 debut, “Ready to Die,” and Combs’ own ascent as a shiny-suited rapper, producer and celebrity. Knight’s Death Row, built on the success of Dr. Dre’s 1992 album “The Chronic” and Snoop Dogg’s “Doggystyle” the following year, was its West Coast antithesis, all masculine bravado and lean, gangsta-funk rhythms.

Knight’s comments served as an accelerant to highly publicized bi-coastal tension within hip-hop at the time, precipitating one of the genre’s most turbulent periods. In the meantime, Death Row would make one major addition to its roster: 2Pac, a.k.a. Tupac Shakur, whom Knight had mentioned earlier in his speech.

At the time of the 1995 Source Awards, 2Pac was an inmate at Clinton Correctional Facility in upstate New York after being convicted of sexual abuse that February. 2Pac remained in the zeitgeist despite being removed from society: his third album, “Me Against the World,” debuted atop the Billboard 200 one month into his incarceration. He would make headlines again in September 1995, when he signed a handwritten contract to join Death Row after Knight agreed to post his $1.4-million bail. The following month, he exited prison, flew to Los Angeles and went directly to the studio. “California Love,” released in December 1995, became his brash reintroduction to the world.

“Out on bail, fresh out of jail, California dreamin’,” 2Pac — brimming with the vigor of a newly liberated man — bellowed over a Joe Cocker piano riff looped with precision by Dr. Dre. “California Love” helped 2Pac reassert himself, while his alignment with Death Row pushed the label to its commercial pinnacle. Alas, the glory leading up to and immediately following the release of 2Pac’s Death Row debut, “All Eyez on Me,” was short-lived, swept up in his dispute with former friend the Notorious B.I.G. and hip-hop’s East Coast-West Coast conflict.

Over the next 15 months, Dr. Dre left Death Row, Shakur died after being shot in Las Vegas and Knight was imprisoned for violating the conditions of his parole. Shortly after Knight’s conviction , the Notorious B.I.G. was fatally shot in Los Angeles, capping off a tragic period in hip-hop’s journey. — Julian Kimble

Lil’ Kim gets “Hard Core”

If a female rapper dropped this verse in 2023, they’d be memed into feminist heaven and give Ben Shapiro a well-deserved aneurysm: “You ain’t lickin’ this, you ain’t stickin’ this / And I got witnesses, ask any n— I been with / They ain’t hit sh— till they stuck they tongue in this / I don’t want d— tonight, eat my p— right”

But this bodacious verse off Lil’ Kim’s “Hard Core” hit record stores in 1996. Today, it’s regarded as a classic of both rap craft and brash female confidence amid the rough-hewn boys’ town of mid-’90s hip-hop. Taking the baton from Queen Latifah and Salt-N-Pepa, Kim would go on to inspire Cardi B, Megan Thee Stallion and (though she’d hate the comparison) Nicki Minaj. There is no “WAP” without “Not Tonight” or “Queen Bitch.“

But Kimberly Jones was a complex, contradictory artist, and “Hard Core” debuted into a rap culture with different ideas of women and sex (one headline in the Source: “Sex & Hip-Hop: Harlots or Heroines?”). Mentored by the Notorious B.I.G. (he picked out the legs-wide portrait for the album’s cover), the 4-foot 11-inch Kim arrived with deep awareness of her appeal and a well of trauma from childhood homelessness and drug-dealing.

A veteran of the group Junior M.A.F.I.A., she put every ounce of her contradictions into “Hard Core,” cutting a track like “Dreams,” where she fantasized about having her way with Babyface, Brian McKnight and D’Angelo, while trying to assert her voice as a writer and MC under the thumb of very powerful men (including Biggie, who got her pregnant while she recorded “Hard Core”).

Kim made art out of her sexual frankness and changed fashion with her avant-garde, ultra-revealing outfits (her 1999 MTV VMAs bodysuit remains seared in millennial minds). After Biggie’s 1997 slaying, she proved her gifts on tracks like “The Jumpoff” and “How Many Licks.” But her career stalled in the mid-2000s, and the hip-hop industry didn’t know how to sustain a sexually liberated woman’s career into middle age. “Hard Core” was ahead of its time, and Kim both reaped the rewards and suffered the costs for seeing the future. — A.B.

Beep beep: Missy Elliott grabs the keys to the Jeep

Elliott didn’t necessarily mean to invent hip-hop’s future with her debut solo album. The way she tells it, she had more immediate matters in mind.

Established by the mid-1990s as half of a songwriting-and-production duo with her longtime creative partner Timbaland — together they’d made hits for Ginuwine, SWV and Aaliyah — Elliott agreed to record 1997’s “Supa Dupa Fly” only as part of a deal with Elektra Records that would give her a label of her own, the Gold Mind, to release records that she and Timbaland wanted to write and produce for other acts.

“It was like, ‘Tim, let’s just hurry up and do this album so I can get to working with the artists,’” she told Rolling Stone last year. “So we completed it in two weeks.”

Rush job or no, “Supa Dupa Fly” ended up remaking the sound of hip-hop and R&B as a playground of spacey funk beats overlaid with Elliott’s sticky vocal hooks and her playful yet streetwise rhymes about sex, weed and driving to the beach in her Jeep (beep-beep).

“She just grabbed me,” says Skrillex, the EDM superstar who recruited Elliott for a cameo on this year’s “Quest for Fire” album. As a kid, Skrillex remembers catching Elliott on MTV, which seemed never to stop playing the video for “The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)” — the iconic Hype Williams-directed clip in which Elliott dances in what looks like a giant trash bag. “I didn’t know about music and production yet, but I was so taken with her skill — just this intangible vibe that literally left an imprint on my soul.”

“Supa Dupa Fly” was an instant smash, becoming the highest-charting debut for a female rapper at the time; it went platinum and picked up a pair of Grammy nominations. At the time, Elliott attributed her success to the fact that her music presented a colorful vision of good times following the slayings of 2Pac and the Notorious B.I.G.

“Rap’s coming around again to stuff that isn’t all about discussing negative things,” she told The Times in 1998. “That’s why I think my music may be getting over.”

Sylvia Rhone, Elektra’s then-chairman, agrees that “Supa Dupa Fly” was “an optimistic breath of fresh air for the culture.” But she points out that Elliott also disrupted prevailing ideas about how women should look and what they should rap or sing about. “When Black women saw Missy, they were able to look into the mirror and see themselves,” says Rhone, who now heads Epic Records. “She was a strong Black woman — full-bodied — writing about subjects that they could identify with. Soon, everyone was trying to jack her style.”

Elliott went on with Timbaland to create subsequent era-defining hits including “Get Ur Freak On” and “Work It,” and in 2015, she rocked the Super Bowl halftime show as a guest of Katy Perry’s. This fall, she’ll become the first female hip-hop artist to be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, an honor voters bestowed on Elliott in her first year of eligibility. — M.W.

Houston’s DJ Screw opens a record store

Screwed Up Records & Tapes wasn’t a very hospitable record store. The interior of the Houston boutique, on Cullen Boulevard in the muggy maw of Southeast Texas, was encased in bulletproof plastic. You could not sample the wares on listening stations. And you could buy only one thing there: heat-warped, dragged-out mixtapes and cassettes from store owner DJ Screw, who hawked wares out of his own house until he opened his shop in 1998.

Yet those tapes were a world onto themselves. Screw’s slowed-down, detuned, disembodied aesthetic became known as “chopped and screwed,” an accurate depiction of both his sample manipulation techniques and how it felt to listen to his music. It was one of the great achievements of Southern rap, music about — and for — altering your mind. (A favorite accompaniment to listening to DJ Screw tapes was “lean,” a mix of codeine cough syrup and soda, served in a giant Styrofoam cup).

Screw (born Robert Earl Davis Jr.) took the unnatural habitat of swampy, concrete-scarred Houston and gave it a perfect soundtrack, one that would go on to influence everyone from both of the Knowles sisters and Travis Scott to director Mike Judge, who used “Still” from Houston’s Geto Boys in his 1996 workplace comedy “Office Space.”

Screw died of a codeine overdose in 2000, a grim reminder of the risks in the subculture he helped forge. In a dark coincidence, the late George Floyd rapped on a number of Screw tapes, long before his tragic murder in 2020 kicked off a global protest movement. Nowadays, Screw is spoken about in reverent tones, a visionary with an idea so simple and transformative that teens are still discovering the thrills of slowing down (and speeding up) songs on YouTube and TikTok. — A.B.

Lauryn Hill makes Grammy history

The Grammys have had, shall we say, a complicated relationship with hip-hop since it first introduced the rap performance category in 1989 and rap album in 1995. Despite the genre’s commercial dominance, creative brilliance and cultural imprimatur, only two hip-hop albums have won the general-field top prize for album of the year.

The first, in 1999, was Lauryn Hill’s heralded debut solo album, “The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.” Hill was already a Grammy favorite, winning rap album and R&B performance for her work on the Fugees’ “The Score” two years earlier. Featuring hit singles “Doo Wop (That Thing),” “Ex-Factor” and “Everything Is Everything,” 1998’s “Miseducation” was a high watermark of Black music, nominated for 10 Grammy Awards and winning five, including album of the year.

Four years later, Atlanta’s OutKast won best album for “Speakerboxx/The Love Below.” Since then, no rapper has won the top prize, and some rap acts, led by Drake, have said they’ll stop submitting their music for Grammy consideration. But for one brilliant night in 1999, Hill was the most acclaimed musician on the planet, fulfilling hip-hop’s long and fraught path from the Bronx to the heights of the industry and culture. — A.B.

Part III

Ghostface Killah revives the Wu

By the end of the 1990s, the popularity of the Wu-Tang Clan, the groundbreaking Staten Island rap behemoth, had waned. With the disappointment around the second slate of Wu-Tang solo albums still lingering, Ghostface Killah — the group’s most enigmatic member — broke the pattern in early 2000 with his second LP, “Supreme Clientele.”

The album’s release was delayed by his journey to Africa in search of spiritual guidance and alternative treatment for what was ultimately identified as diabetes, a four-month stint at Rikers Island in New York City in an atttempted robbery case upon his return and the flooding of bandmate and producer RZA’s basement studio.

The end result, a true labor of love and chaos, was worth every delay. After aiming to establish himself as a solo artist on 1996’s “Ironman,” Ghostface delivered the first great rap album of the 2000s less than five years later.

“Ironman, lead us to the promised land,” Ghostface, he of the Ironman-Tony Stark alter ego, chants during the album’s intermission and outro. First and foremost, “Supreme Clientele” is an upper-echelon showcase for Ghostface’s gift for gab, each verse packed with joyfully perplexing details. On “Nutmeg,” the exultant opener, he’s “lamping in the throne with the King Tut hat.” On “The Grain,” he envisions Queen Elizabeth rubbing his leg at the opera with “ketchup on her dress from a Whopper.” On “One,” he boasts of rhymes made of garlic and, perhaps most infamously, compares his lyrics to baked ziti on “Apollo Kids.” Meanwhile, “Cherchez LaGhost” bends the party record format to Ghostface’s eccentricities.

“Ghost was at the pinnacle of his lyrical skill,” RZA told The Times by telephone. “Everything about that album was a pinnacle.”

Although RZA handled most of the production, Wu-Tang associate Mathematics (“Mighty Healthy” and “Wu Banga 101”), Juju of the Beatnuts (“One”) and even Ghostface’s barber, Black Moes-Art (“Nutmeg”) make key contributions. Throughout, the soul samples that defined a large section of 2000s hip-hop are omnipresent, reflecting Ghostface’s personal tastes: It’s easy to picture him listening to Brown, Isaac Hayes and Solomon Burke at his leisure.

“Supreme Clientele” is the moment Ghostface Killah guided the Wu-Tang Clan into the new millennium by elevating the free-form expression that’s become the hallmark of his artistry. In true Ghostface fashion, he accomplished this feat clad in bejeweled bathrobes and Clarks Wallabees, captured in 35mm by the likes of Director X and Chris Robinson. Tony Stark himself would never be so bold. — J.K.

Jay-Z and Nas stage an epic dis war

By 2001, Jay-Z had already amassed a six-year string of anthems for the streets, the pop charts and the clubs. Yet “The Blueprint,” released on 9/11, was something different altogether. The usually guarded Shawn Carter displayed a glimpse of vulnerability on his most musically soulful statement to date. As Hov contemplated the pitfalls of stardom (“Heart of the City (Ain’t No Love)” and love (“Song Cry”), he still found time to flex his lyrical superiority (“U Don’t Know”).

Of course, “The Blueprint” will forever be linked to Jay-Z’s epic rivalry with rapper Nas. The Kanye West-produced, Doors-sampling “Takeover” ignited the mother of all rap battles, as the showdown between the two rhyme juggernauts captured the imagination of hip-hop fans everywhere. The winner? After his brutal response “Ether,” a thoroughly reinvigorated Nas was declared the People’s Champ, while Jay basked in the glow of “Blueprint,” an unimpeachable masterpiece. — K.M.

Eminem gets one shot with “8 Mile”

Mom can never make spaghetti again without the hook from “Lose Yourself” playing on a loop in your brain.

In 2002, Eminem was just about the biggest star in music and a source of consternation among right and left alike for his hyper-violent, debatably misogynist and homophobic lyrics. Under mentor Dr. Dre, he’d followed N.W.A’s legacy of making hip-hop seem genuinely dangerous again (just watch his witty 2000 VMAs performance, with a hundred Eminem lookalikes, ostensibly seduced into his worldview).

But his life story was just as compelling: a poor white kid entranced by Black hip-hop, a technical genius in love with rap music but justifiably uncertain of his place in it. “8 Mile,” a lightly fictionalized biopic of his early years in Detroit’s battle-rap scene, drew heavily from Eminem’s life, and the MC proved a worthy and compelling actor in the part.

But “8 Mile” stands on its own as one of the best movies about the craft of rapping itself — the grueling work to hone your instrument and aesthetic, the ways the genre requires outsize charisma at odds with the grind and insecurities of your daily life, and the absolute thrill of roasting a dude into catatonia. The movie’s exultant final battle-rap scene will still make you want to flip your couch over from the adrenaline rush. — A.B.

Outkast and Atlanta take over hip-hop

In 1995, Outkast’s Big Boi and André 3000 walked onstage at the second Source Awards at New York City’s Paramount Theater, where the Atlanta duo had just been awarded best new group of the year by the influential rap magazine. The jeering crowd, consisting mostly of the New York and L.A. rap cognoscenti, didn’t respect outsiders in a genre they either invented or dominated, and they nearly heckled OutKast offstage, but not before André reeled off a prophesy.

“It’s like this, though, I’m tired of them closed-minded folks,” André said. “It’s like we got a demo tape and don’t nobody wanna hear it. But it’s like this, the South got somethin’ to say.”

Eight years later, in 2003, their hometown was inarguably the center of the world for hip-hop.

MF Doom goes on a heater

While walking through Long Beach’s Aquarium of the Pacific in 2002, producer Madlib told a Times reporter that there were two names on his dream collaborators list: acclaimed Detroit beatmaker J Dilla and the masked villain of hip-hop known as MF Doom. Later that same year, he’d get his wish, when a sample of his beats passed telephone-style from Los Angeles to Doom’s residence in Kennesaw, Ga.

Madlib and Doom teamed to form Madvillain, whose one and only album — nearly scrapped after unfinished demos were stolen and leaked online — was the cult classic “Madvillainy.” Between 1940s movie snippets and over layered samples, Doom weaves his lyrics with breathless ease, fitting nonsensical segues into perfectly irregular rhythms from start to finish.

Six months after “Madvillainy” (and three months after releasing “Venomous Villain” under one of his alter egos, Viktor Vaughn), Doom returned with “Mm…Food,” flexing as both a rapper and a producer on his most-acclaimed solo project. Nineteen years later, “Madvillainy” and “Mm… Food” sit atop his catalog, having influenced a generation of artists to come. Take it from Q-Tip, who called Doom “your favorite rapper’s favorite rapper” when news of his death was announced on the final day of 2020. — K.D.

Mixtapes go from the car trunk to the internet

In between the peak of the CD era and the rise of streaming, the record industry was in an outlaw era. Napster instantly pulled the floor out from under major labels; iTunes made it easy to burn custom mix CDs of favorite songs to pass among friends. Then as now, hip-hop moved with a particular speed that needed something quicker, more gray-market than the dominant commercial formats.

Mixtapes — collections of original material, re-worked tracks from other artists, singles, remixes and other odds-and-ends — were around long before 2005, but that was the year they came into their own as a medium in the internet age. One no longer had to go to the trunk of a rapper’s car to find one — they were now easily shareable online. That year, the download site Datpiff debuted as a central clearinghouse for mixtapes from emerging artists and material from superstars aimed more at street-level. Acts like Clipse and Young Jeezy took off on the site, and their careers rocketed to national renown.

One of the hallmark achievements of the era was “Dedication,” the first mixtape collaboration from Lil Wayne and a young Atlantan named DJ Drama, whose Gangsta Grillz series would soon become the hottest ticket in hip-hop. It packed 29 songs into a loosely stitched showcase of Wayne’s free-associative genius, previewing the late-aughts era where he’d rule the Hot 100. Gangsta Grillz caught so much attention that it led to a law enforcement raid on Drama’s compound in 2007. Mixtape culture roiled across the pond too: “Run the Road,” a 2005 compilation of the U.K.’s emerging grime scene, offered an icy new perspective on urban malaise. — A.B.

Three 6 Mafia wins an Oscar

“Academy Award winners Three 6 Mafia.” Still feels great to say it.

The Memphis goth-rap collective was an underground legend by the mid-2000s, with a bleak and murky sound in love with sex, drugs and horror films. When producer John Singleton and director Craig Brewer needed songwriters for a central theme to “Hustle & Flow,” a tale of a Memphis pimp (Terrence Howard) trying to build a new life in hip-hop, there was only one place to turn.

The film was an unexpected smash, and Three 6 Mafia’s “It’s Hard Out Here for a Pimp” — rapped by Howard and sung by Taraji P. Henson in the film — earned an Oscar nomination for original song alongside Dolly Parton and “In the Deep” from eventual best picture-winner “Crash.” Three 6 Mafia was the longest of long shots, but the collective brought down the house performing with Henson during the telecast.

Queen Latifah was visibly delighted when she opened the envelope and announced that Three 6 Mafia had won. Dressed in ball caps and tooth jewelry, an ecstatic Juicy J, DJ Paul and Frayser Boy (along with Crunchy Black, who joined them onstage) thanked everyone they could think of in deep Southern accents (including George Clooney) and ambled offstage having ascended into film and music history.

“You know, I think it just got a little bit easier out here for a pimp,” host Jon Stewart said. “Now that’s how you accept an Oscar!” — A.B.

Soulja Boy goes viral

The same year that Kanye West and 50 Cent went head-to-head in a landmark album-sales battle backed by two of the industry’s most powerful labels, a 17-year-old Atlanta native named DeAndre Way uploaded a rough-hewn snap track called “Crank That (Soulja Boy)” to his MySpace page. In spite (or because) of its clipping vocals and beat made from stock sounds from a demo version of FL Studio, the song spread like wildfire, its visibility boosted by a creative yet imitable dance that had kids across the country copying his entire flow (with or without his trademark tall tee).

Arguably even more impactful than the song, which spent seven weeks atop the Billboard Hot 100, was the direct-to-consumer approach Soulja Boy rode to success. The Atlanta rapper didn’t just upload the song to his own MySpace page, he also flooded music download sites such as LimeWire with links, often falsely titling the song as a different trending hit to trick listeners into downloading. By bypassing the traditional label system, he tore down the walls that defined music distribution at the time, opening the doors for future artists to follow his footsteps once SoundCloud emerged in the 2010s.

Eventually, the major labels came to him — Soulja Boy signed with producer Mr. Collipark’s Interscope Records imprint and re-released the song, with a proper music video, later that year. — K.D.

Lil Wayne becomes unstoppable on “Tha Carter III”

From the second half of George W. Bush’s presidency through the opening years of the Obama administration, Lil Wayne mastered the art of rap-as-volume-shooting. Once the youngest member of the Hot Boyz, the pride of New Orleans’ Hollygrove neighborhood grew into Cash Money Records’ cash cow. Shouldering the success of the enterprise, Wayne capped off his evolution by unleashing hard drive upon hard drive of music via mixtape, in addition to the first two “Carter” albums. When he came up for air, it was to burn through remixes and features at a similarly implausible rate.

Wayne boldly proclaimed himself the best rapper alive on 2005’s “Tha Carter ll.” 2008’s long-delayed and oft-leaked “Tha Carter lll” was Wayne reaching for hip-hop’s crown to place atop his locs.

After opening the album with “3 Peat,” Wayne eagerly receives the baton from Jay-Z on “Mr. Carter,” sprinting forward to place himself in conversation with legends. “And next time you mention Pac, Biggie or Jay-Z / Don’t forget Weezy, baby!” he raps with gusto. On “Dr. Carter,” he resuscitates hip-hop over a slick David Axelrod sample courtesy of Swizz Beatz. With Babyface’s help, he plays suave womanizer on “Comfortable.”

Wayne’s willingness to experiment yielded “Lollipop,” one of the biggest songs of ‘08 and about as successfully esoteric as anything he’s ever done. And if you just wanted to hear him black out, there was the hookless, similarly inescapable “A Milli.”

Both 2004’s “Tha Carter” and “Tha Carter ll” may have eclipsed “Tha Carter lll” in quality, but the latter, which sold more than 1 million copies in its first week, stands out as the moment Wayne became the center of hip-hop’s universe, simply by inhabiting his own planet. — J.K.

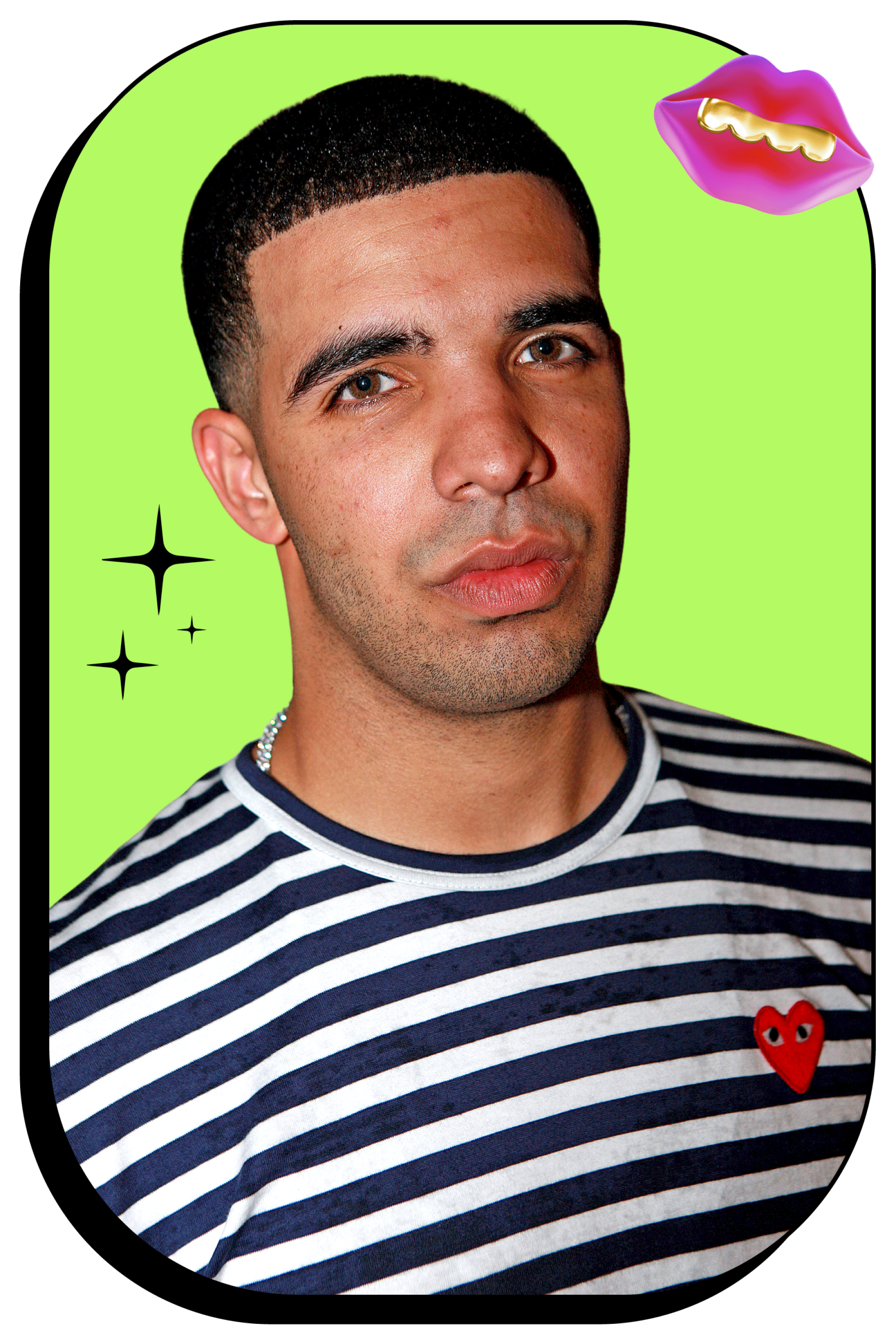

Drake and the rise of Sadboi rap

Hip-hop has always included some introspection and sensitivity alongside the genre’s traditional masculine bravado. But 2009 was a high water mark for the moody, melodic strain of Sadboi rap, where no amount of fame or money could fill the void left by the one that got away.

That year, the crown price of softies, Drake, scored this first Top 10 single with “Best I Ever Had.” The love-struck song showed his way around a gently crooned hook that would become de rigueur in hip-hop for a generation to come.

Also that year, Kid Cudi — the rapper, actor and anime producer — dropped his era-defining LP “Man on the Moon: The End of Day.” Executive-produced by the like-minded Kanye West, fresh off his own self-lacerating “808s & Heartbreak,” the album blended psychedelic vibes, indie-rock melodies (courtesy of producers MGMT and Ratatat) and a vocal delivery somewhere between rapping, stoned singing and voice-over narration.

The LP’s centerpiece, “Day N Nite,” got a second wind when its main hook (if you’re a millennial, you know exactly when the lonely stoner frees his mind) got remixed by the blog-house duo Crookers into a throbbing floor-filler. If you struck out looking for love at Bardot or Cinespace, Cudi’s voice was right there to pick you up again. — A.B.

Nicki Minaj eats brains on “Monster”

Minaj was already a multiplatinum headliner by the time she laid down her song-stealing verse on Kanye West’s all-star romp “Monster.” How iconic was her appearance? An in-the-zone Minaj proclaimed, “You could be the king, but watch the queen conquer,” overshadowing Rick Ross, West and most notably Jay-Z, who throughout his storied career had garnered a reputation for eclipsing collaborators on their own tracks. Minaj’s performance, as much a defiant declaration of women’s empowerment as a gloriously unhinged lyrical flex (“OK, first things first, I’ll eat your brains...”), ranks as one of the most memorable mic drops in rap history. — K.M.

Part IV

Tyler, the Creator becomes a brand

In February 2011, Tyler, the Creator ate a live cockroach and “hanged” himself in the black-and-white video for his song “Yonkers.” Near the end of the year, he opened the brick-and-mortar Odd Future store on Fairfax Avenue in L.A.. In between, he established himself as an anti-everything personality with a fervent cult following, one that grew over the next 10-plus years as Tyler’s music and brand matured and expanded, always on his own terms.

The seeds for Tyler’s thunderous year were planted in 2007, when he and an L.A. collective of internet-raised rappers, producers and skaters launched Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All, shortened to Odd Future, or OFWGKTA. The polarizing band of tricksters — which at one time or another included future solo acts Earl Sweatshirt, Frank Ocean and Syd — quickly built a boisterous fan base through self-released mixtapes and off-the-wall YouTube videos.

Tyler’s 2011 album “Goblin” backed up the abrasiveness of “Yonkers” with equally confrontational tracks, fueled by his disdain for religion, authority, school and just about everything else. Horrorcore lyrics placed him in the cross-hairs of parents and earned him a string of protesters outside his shows, while simultaneously endearing him to a younger generation that hung on each new antic. The Odd Future shop closed its doors in 2015, but the flagship store for his Golf Wang streetwear line opened just down the block a couple years later, with lines out the door to this day. Golf Wang has blossomed into a multimillion-dollar business, while Tyler’s annual Camp Flog Gnaw festival, held at Dodger Stadium, has become one of L.A.’s most-anticipated musical events. This year’s edition, scheduled for Nov. 11-12, sold out before a lineup was even announced. — K.D.

Chief Keef’s “I Don’t Like” launches drill

Pound for pound, few singles have had as much of an impact on the hip-hop that came afterward than Chief Keef’s “I Don’t Like.”

Keef was still a teenager when he, producer Young Chop and guest Lil Reese cut this track, a churning, spattering, taunting roll call of Keef’s gripes that introduced the world to drill, an unrelenting Chicago style of hip-hop. The song was thrilling yet unnerving, an heir to 50 Cent’s street noir. But as it was also a gateway into the very real underbelly of Chicago gang crime and gun violence that has claimed so many of its young Black residents.

Keef, who already had a formidable criminal history as a juvenile, nearly sent himself back to jail after prosecutors alleged he violated probation when he shot a gun at a firing range during a video interview for Pitchfork. After Kanye West jumped on a remix, Keef became the center of a rap-world maelstrom about the borders between exhilarating outlaw music and the real bloodshed that birthed it.

Keef would eventually mellow out, and drill crossed continents and oceans. London’s grime scene adopted many of its harsh textures and rapid hi-hats. And in New York, it became the sound of a disaffected Black youth subculture, yielding stars like Pop Smoke and DD Osama and earning the ire of cops and government all over again. More than a decade on, “I Don’t Like” doesn’t just bang, it echoes. — A.B.

The birth of the “Migos flow”

It was the cadence that took over hip-hop, with lyrics inspired by Medusa and the Italian fashion house that placed the serpent-coiffed figure of Greek mythology at the forefront of its brand. Migos’ “Versace” flaunted the now-universal triplet flow at its most devastating, dancing over twinkling bells that left plenty of space for the group’s ad-libs to slice through.

“Versace” would spark a run that would cement the trio as the most important rap group of the 2010s. The song eventually cracked the Billboard Hot 100 at No. 99 after Drake propelled it further via a remix, but its impact stretches further than a chart can measure — Travis Scott, Lil Baby and even Ariana Grande have made hits using the “Migos flow,” while “Versace” remains an essential track in the Migos’ storied catalog. Fun fact: Per Genius, Quavo, Offset and the late Takeoff rap the word “Versace” 163 times on the original song, making up 32% of the total lyrics. — K.D.

Killer Mike chokes up over Ferguson

Chance — or maybe fate — put Killer Mike onstage in St. Louis on Nov. 24, 2014, just hours after a grand jury declined to indict a white police officer, Darren Wilson, in the killing of Michael Brown, the unarmed Black teenager whose death that summer ignited large-scale protests in the nearby town of Ferguson, Mo. As he began a concert by Run the Jewels, his bomb-throwing hip-hop duo with the MC and producer El-P, Mike seized the moment to channel the outrage coursing through the area — the outrage coursing through the country — in a passionate pre-show speech that quickly went viral after a fan posted video of it online.

Having told the crowd at St. Louis’ Ready Room that he and El-P typically came onstage to the sound of Queen’s “We Are the Champions,” Mike said in a voice cracking with emotion that “no matter how much we do it, no matter how much we get s— together, s— comes along and kicks you on your ass, and you don’t feel like a champion. So tonight I got kicked on my ass when I listened to that prosecutor.” Through tears, he went on to explain why he feared for the safety of his sons before vowing to fight the “war machine” of American policing — “a war machine that uses you as a battery.” Then the duo’s DJ dropped a beat and the place exploded with pent-up fury.

By this point in Killer Mike’s career, which began with his affiliation with Atlanta’s Outkast, he’d already positioned himself as an inheritor of the noisy agit-rap tradition embodied by Public Enemy and Boogie Down Productions; “Run the Jewels 2,” which came out as a free download in October 2014, pondered the relationship between systemic racism and police brutality in songs like “Early” and “Close Your Eyes (And Count to F—).” But the speech in St. Louis solidified Mike’s presence as one of hip-hop’s most visible activists, a role he’d fulfill over the next decade as he spoke out — not always to uniform praise from within rap circles — about the most effective forms of civil disobedience, about the importance of Black gun ownership, about his support of Bernie Sanders’ presidential run.

Six years after Ferguson, amid nationwide protests sparked by another police killing — this one of George Floyd in Minneapolis — he and El-P released “RTJ4” two days ahead of schedule. “F— it, why wait,” they said in a statement. “The world is infested with bulls— so here’s something raw to listen to while you deal with it all.” — M.W.

Joe Budden goes from rapper to podcaster

Today he might be the second-most-famous Joe (after Rogan) in all of podcasting. But when Budden started his self-titled show, he was best known to many as a journeyman MC whose biggest hit, 2003’s thumping “Pump It Up,” was more than a decade behind him.

Budden’s ease behind a microphone — honed during his rapping days and during stints on New York’s Hot 97 and VH1’s “Love & Hip-Hop” — made him a natural fit for the chatty podcast realm, then exploding in the wake of “Serial’s” smash success. But so too did Budden’s inveterate crankiness and his unquenchable thirst for gossip; one early sign that people were listening came when he dissed Drake on his show — then watched with delight as the superstar rapper responded in his verse on a French Montana single.

The frank yet well-informed commentary that defines “The Joe Budden Show” — think of him as you would a retired point guard breaking down a game on ESPN — has since been emulated across the rap media-sphere, changing the way fans consume news and challenging the authority of established journalists. — M.W.

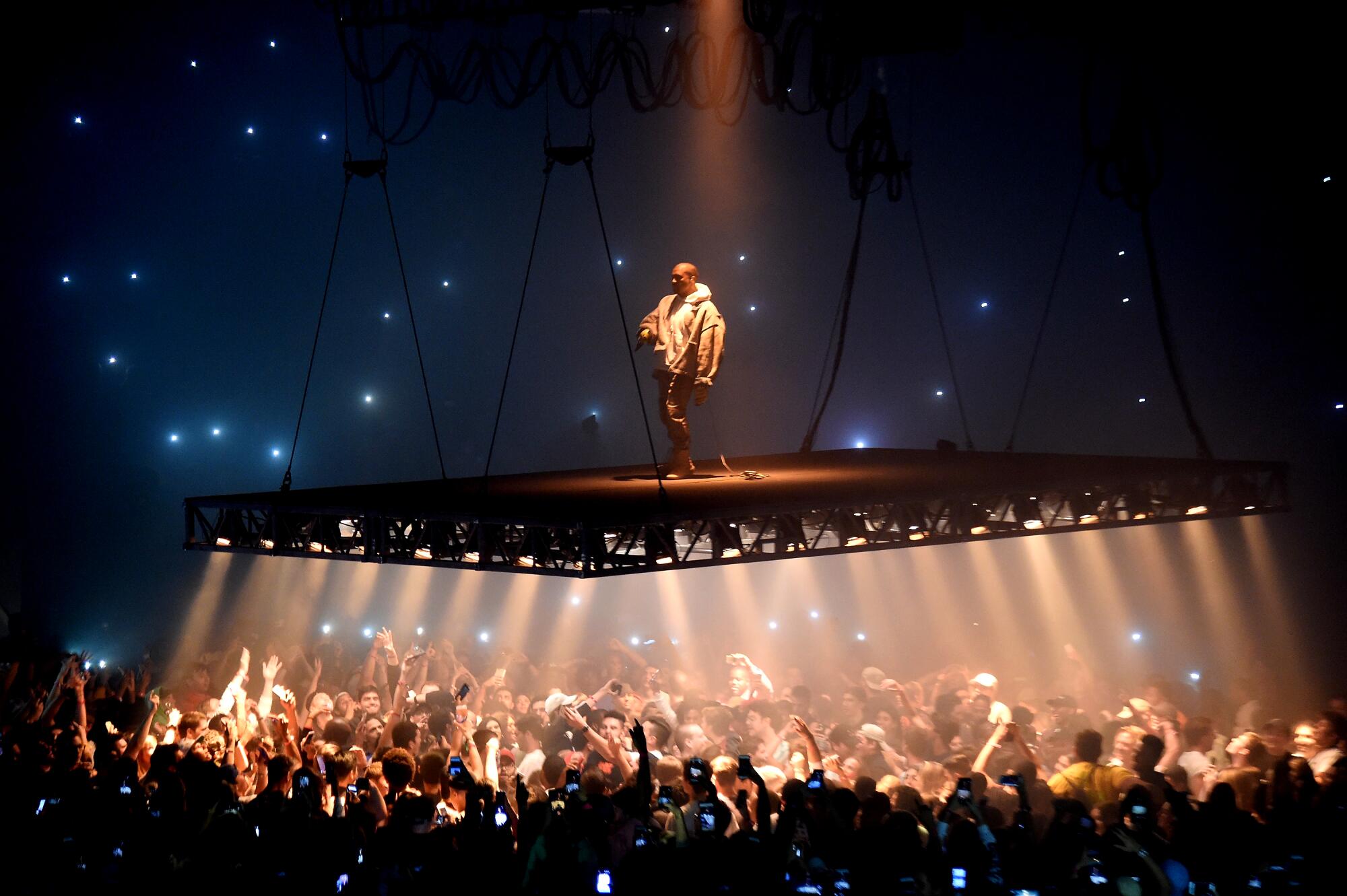

Kanye West walks onto the ledge

To put it mildly, 2016 was a year when a lot of things changed in America. One thing that kept a portion of the country on edge was West’s album “The Life of Pablo,” a high point in his midcareer turn to gospel fugues and grandiose productions.

West, somewhere between an absolute perfectionist and an incurable neurotic, decided that he wasn’t quite satisfied with the final edit of “Pablo” and would embark on a new experiment — the album would never actually be finished. After the widespread adoption of streaming services, he could keep futzing with it to his heart’s content and upload new versions as he deemed fit. Most tweaks were minor mix updates, though he did add a new outro and put back some guest verses.

2016 was also the year he quite literally walked out to a ledge and looked into the abyss. First, with a groundbreaking stage setup for his Saint Pablo tour, where he performed atop an elevated platform that hovered over the moshing audience below. But also, after a life of struggles with mental illness, he first announced his support for Donald Trump during his presidential campaign and checked himself into a hospital after a paranoid breakdown. West’s story ends with an ugly fall from grace, but in 2016, he was still a nervy, restless artist never content to sit still. — A.B.

Nipsey Hussle opens the Marathon Clothing store

Hussle was thinking well beyond music when he boldly declared, “I ain’t nothin’ like you f— rap n—” on his 2018 single, “Rap N—.” The rapper and entrepreneur walked it as he talked it; being “Neighborhood Nip” meant pouring resources back into the Crenshaw community where he was born and raised.

Hussle found his niche as an independent artist before releasing his debut album, “Victory Lap,” through a partnership with Atlantic Records in 2018. He brought that DIY spirit to each of his business ventures, including the opening of his Marathon Clothing store at Crenshaw Boulevard and West Slauson Avenue in June 2017.

The store (which Hussle founded along with his brother, Samiel “Blacc Sam” Asghedom, as well as Karen Civil and Steve “Steve-O” Carless) served as a brick-and-mortar retail location for his Marathon Clothing brand, but it also gave customers access to exclusive content through the use of an app. It was an ambitious endeavor, but its true significance was its location: It was where Hussle and Blacc Sam previously got into fights, had run-ins with the LAPD and where Hussle sold his mixtapes from the trunk of his car.

Hussle was dedicated to being an example for people who grew up like he did, in South Los Angeles and beyond. To that end, the Marathon Clothing store was a physical manifestation of Hustle’s ethos — a mentality rooted in self-sufficiency and ground-up community work. Eventually, Hussle purchased the shopping center and made it the home base for his business empire.

Tragically, that became the very place where Hussle met his demise. In March 2019, he was shot and killed in the parking lot in front of the Marathon Clothing store. The flagship location closed after his murder, but the site now serves as a memorial for Hussle, drawing people from all over the world to pay their respects. Fittingly, the city renamed the intersection of Crenshaw and West Slauson: It’s now officially known as Ermias “Nipsey Hussle” Asghedom Square. — J.K.

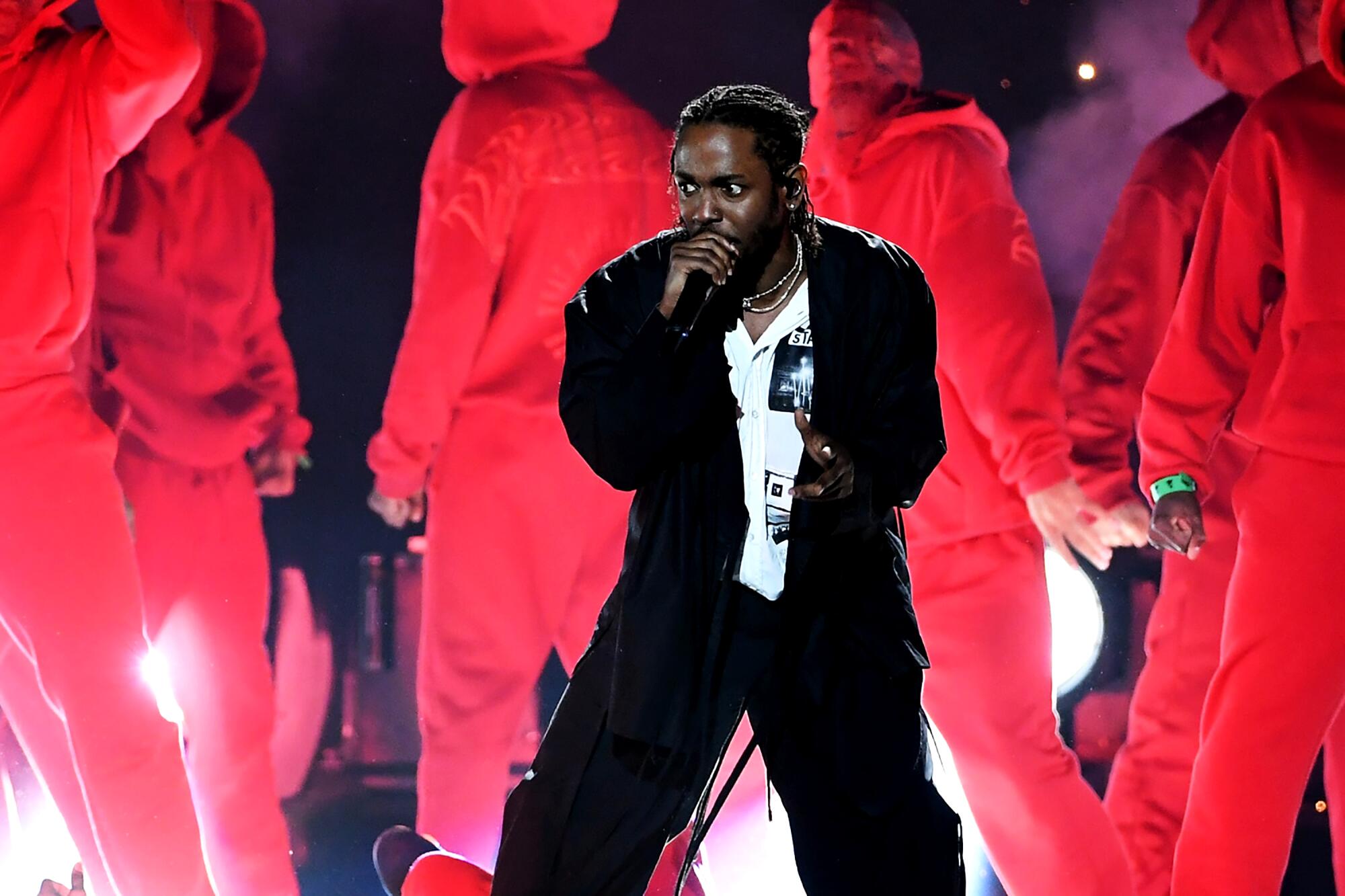

Kendrick Lamar wins the Pulitzer

A hip-hop artist had never received the prestigious Pulitzer Prize for music. That changed in 2018, when Compton’s Kendrick Lamar was awarded the honor for his album “Damn.,” praised by the Pulitzer committee as “a virtuosic song collection unified by its vernacular authenticity and rhythmic dynamism that offers affecting vignettes capturing the complexity of modern African American life.” A year later, Lamar opened up to Time magazine on the importance of rap joining classical and jazz music at the elite Pulitzer table. “It’s one of those things that should have happened with hip-hop a long time ago,” he said. “It took a long time for people to embrace us — people outside of our community, our culture — to see this not just as vocal lyrics, but to see that this is really pain, this is really hurt, this is really true stories of our lives on wax.” — K.M.

Pop Smoke crashes the party

In 2019, Bashar Barakah Jackson was the undisputed king of New York. The 19-year-old Brooklyn drill artist known as Pop Smoke took the sonic template from Chief Keef nearly a decade earlier, but added his own deep, husky intonations for a one-of-a-kind spin on the sound. It took off instantly: “Welcome to the Party” and “Dior” seemed to rip through every speaker in the city, and the latter hit No. 22 on the Billboard Hot 100.

The heady scene around him freaked out New York City cops to the point where they pulled him off the bill at the Rolling Loud festival, fearing violence and sparking a fresh debate about policing young Black men in hip-hop. But Pop Smoke was, up until the moment of his murder in L.A. in 2020, defining a new era in the birthplace of hip-hop. Two posthumous No. 1 albums were a valediction. — A.B.

America learns the meaning of “WAP”

One of hip-hop’s great gifts is its ability to conjure new slang from the ether. In 2020, everyone from TikTok teens to spluttering Fox News viewers knew exactly what “WAP” stood for.

The ravenously, joyfully filthy single from Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion was a hit like none other right out of the gate. Living up to the grand traditions of Salt-N-Pepa and Lil Kim, barely a lyric from the single is printable in a family newspaper, but it was horny enough to cause far-right podcaster Ben Shapiro to literally seek out medical advice regarding the plausibility of the song’s premise (to the bemusement of women everywhere).

But it was also a commercial smash, breaking records for first-week streams in the U.S. and parking a big Mack truck right in the little garage of the Billboard Hot 100 (it debuted at No. 1). Get a bucket and a mop, that’s the song of the year. — A.B.

Drakeo the Ruler comes home

The creator of nervous music and the inspiration for a new generation of L.A. rap had just lost three years of life to the Men’s Central Jail. Although he was acquitted of murder in 2019, he remained in jail until November 2020, after then-Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey refiled criminal gang conspiracy charges that hemmed him up for an additional 16 months. (Drakeo eventually took a plea deal that granted his immediate release.)

In 2021, his rightful coronation finally arrived in the form a sold-out show at the Novo. It was the culmination of everything he and his legal team had fought for: a prime-time slot in downtown Los Angeles, with friends and family backstage and adoring fans in the audience hanging on every word. “To see him in all his glory, everyone there, camera phones up, singing his lyrics — it had been so overdue because of his legal trouble and COVID — so to finally see it happen was dope to watch,” radio personality and journalist Rosecrans Vic told The Times in 2021.

Less than two months later, Drakeo was fatally stabbed while backstage at the Once Upon a Time in L.A. festival. The killing remains unsolved. — K.D.

Puerto Rico is in the house

The biggest hip-hop album — the biggest anything album — of 2022 didn’t come from the longtime strongholds of L.A., New York or Atlanta. It came from Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, where Bad Bunny developed the signature blend of reggaeton, mambo, bachata, synth-pop, dembow and hip-hop that defines “Un Verano Sin Ti,” his blockbuster fourth studio LP.