‘Eight White Nights: A Novel’ by André Aciman

- Share via

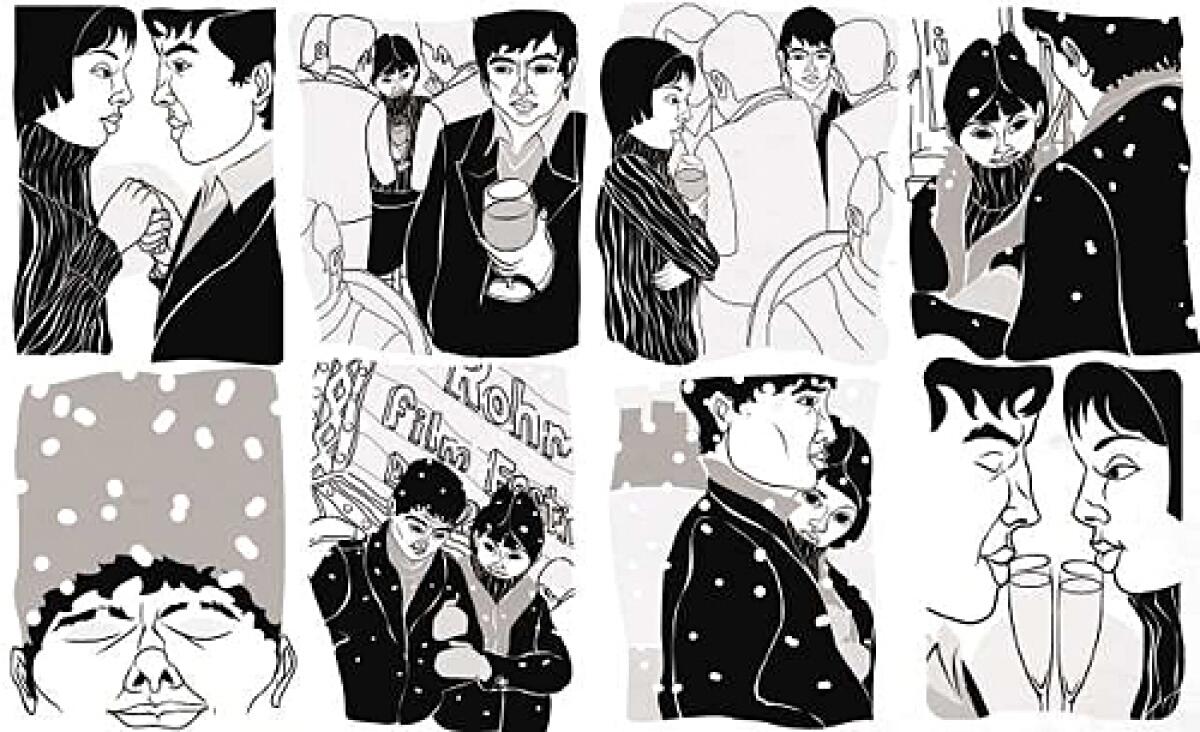

Eight White Nights

A Novel

André Aciman

Farrar, Straus & Giroux: 360 pp., $26

It would be simplistic and only partly true to sum up André Aciman’s “Eight White Nights” -- about the advances and retreats of a love affair -- as Lucy holding Charlie Brown’s football and yanking it as he is about to kick it.

This story’s Charlie, fearing a rebuff, withholds his kick as often as this Lucy swoops the ball away; and it is to preempt his withholding that she swoops it.

Anyway, to think of the etiolated Manhattan social milieu of Aciman’s novel in terms of Middle America’s “Peanuts” is to compare a soufflé -- somewhat over-egged -- to hash. Aciman’s incessantly self-questioning narrator evolves sentences of Proustian complexity and length; his Clara, as vulnerable as Cleopatra and as dangerous as her asp, is glitteringly smart. Their eight-day joust is a pas de deux of finely bruised shins. The rhythm is set by nightly visits to a festival of films by Eric Rohmer, himself a master of erotic dance and evasion.

The narrator, unnamed, is a young man of seemingly comfortable means (no mention of a job) who finds himself invited to a stylish Christmas Eve party on the Upper West Side. Alone and forlorn by the Christmas tree, he is simultaneously accosted and smitten by a strikingly attractive woman who announces: “I am Clara.” Ruminating elaborately, he parses the phrase, which seems to stake a warrior’s claim upon him.

An instant intimacy flares, a shared made-up world of words, a comical lampooning of other guests. For 80 pages, nearly a quarter of the novel, the two of them move through the party’s shifting circles, Clara alternately attaching and detaching herself; hungrily seductive at times, distant at others. At one point, the narrator finds her avidly kissing a man; later, she explains that she is simply easing the dismissal of an ex-lover who has tearfully pursued her.

When the narrator leaves, she walks into the snow with him before going back inside. He sits in a nearby park, shaken and obsessed: “There was more of her in me than there was of me.” He pictures himself returning to the party, welcomed; he pictures domestic moments hearing her grind coffee, noticing the odor of her pet litter. He doesn’t just imagine such scenes; he imagines remembering them.

Imagined scenes, conversations and intimacies occupy at least as prominent a place in “Eight White Nights” as the actual story does. Some of the most eloquent courtship passages take place in the narrator’s mind. Richly elaborated as some of them are, they give the book a claustrophobic quality; eventually, we may feel reluctant at having the action blurred so that we can be conducted indoors for another bout of churning introspection.

The active scenes in this perpetual loop -- rise, fall, rise, fall, rise (perhaps) -- of an erotic obsession can be vivid and refreshing. There is a compellingly written winter excursion up along the Hudson, with its cracking ice. The day passes with a perceptible warming of Clara’s seeming on-again, off-again relationship with her seeming lover.

Seeming, because of the unreliability of this acutely sensitive, acutely perceptive, acutely self-abasing narrator. We read of his elaborate advances and petulant retreats; and of her alternate rebuffs and seductions. Clara’s warming intensifies into passionately sensual incursions; it is he who hangs back with a mumble of “too soon, too sudden, too fast.”

And dimly, through his occluded view -- a view he seems to prize less than the elaborate clouds that blur it -- we descry the witty woman who does, in fact, love. It is a combative love; its changeable goadings are surgical, seeking to amputate the self-indulgent hesitations of her would-be lover.

Our glimpses of Clara are the liveliest and most engaging part of the book. They slip, almost as if by accident, through the narrator’s emotional meanderings. Even when ostensibly about her, the subject is himself, and the subject wears out as it elegantly talks itself into near invisibility.

“Eight White Nights” is set about with literary and artistic mirrors. The title and the ever-present snow suggest Dostoyevsky’s own novel of winter longings. The extended party at the start recalls the pivoting emotional combinations and transformations in the great centerpiece of Jean Renoir’s “The Rules of the Game.” And Rohmer’s films, seen each night by the lovers, are not just references but also an explicit model for their advances and retreats.

What Rohmer suggests, though -- indelibly, yet with a breathtaking, buoyant elusiveness -- Aciman pounds away at explicitly, devotedly. And then there is Proust. The author’s intricate sentences, sometimes at paragraph length and studded with subordinate clauses that breed more clauses, do suggest a Proustian model. But there is a world of difference.

For one thing, “Remembrance of Things Past” ranges through a whole society and an immensely rich culture, along with the emotional complexities of its narrator. The social and cultural scope of “White Nights” takes in little more than a few West Side Manhattan blocks. More important, though, Proust’s novel represents one of the most profound artistic embodiments in literature; Aciman’s is at best a virtuoso performance.

Eder, a former Times book critic, was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for criticism in 1987.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.