The new sounds of protest: Political music in the age of Trump

- Share via

Music has always been political, be it the debate over decency inspired by Elvis Presley’s hip shaking, Woody Guthrie pasting the message “this machine kills fascists” on his guitar or even, long before “Hamilton,” a century-old opera that about Native American life.

Today, amid a tense and divisive political climate, the sound of resistance has as much to do with inclusion as with strict opposition. In art — and in policy — the line between the personal and the political feels increasingly blurred, as made clear by the #MeToo movement and heated discussions over immigration rights, sexual harassment and gender and racial equality.

Some artists are raising a fist while others are looking for empathy, but it’s all in the name of building a community. Here, in this series of stories, The New Sounds of Protest, The Times offers a look how varying artists are making sense of life in 2018.

—Todd Martens, Pop Music Editor

In today’s divisive political climate, pop artists are shaping the new sound of protest music

By Mikael Wood

One of the most effective protest songs of 2018 doesn’t mention Donald Trump by name.

It doesn’t push back directly against one of his controversial policies, nor does it question the means by which he was elected president. It doesn’t refer to government at all, really, unless you count an image of Uncle Sam kissing a man.

The song is “Americans,” the final track on Janelle Monáe’s album “Dirty Computer,” and what it does is argue that the promise of this country is still something to get excited about — and still something to fight for.

Kamasi Washington’s ‘Heaven and Earth’ proves jazz’s vitality and political power

By August Brown

Saxophonist Kamasi Washington helped pioneer an L.A. scene that freely melds free jazz with hip-hop and Afro-centric spirituality. Jazz has always been radical in its deconstructions of form and forceful assertions of black identity. Washington notes that his new album is political music, even at its most oblique, in the sense that it taps into and tries to understand the primal forces that animate our attitudes and choices.

The current political climate is “a cyclical thing that’s happened before and it will continue to happen until we change our approach,” he said. “I’m looking beyond the problem and looking to the cause.”

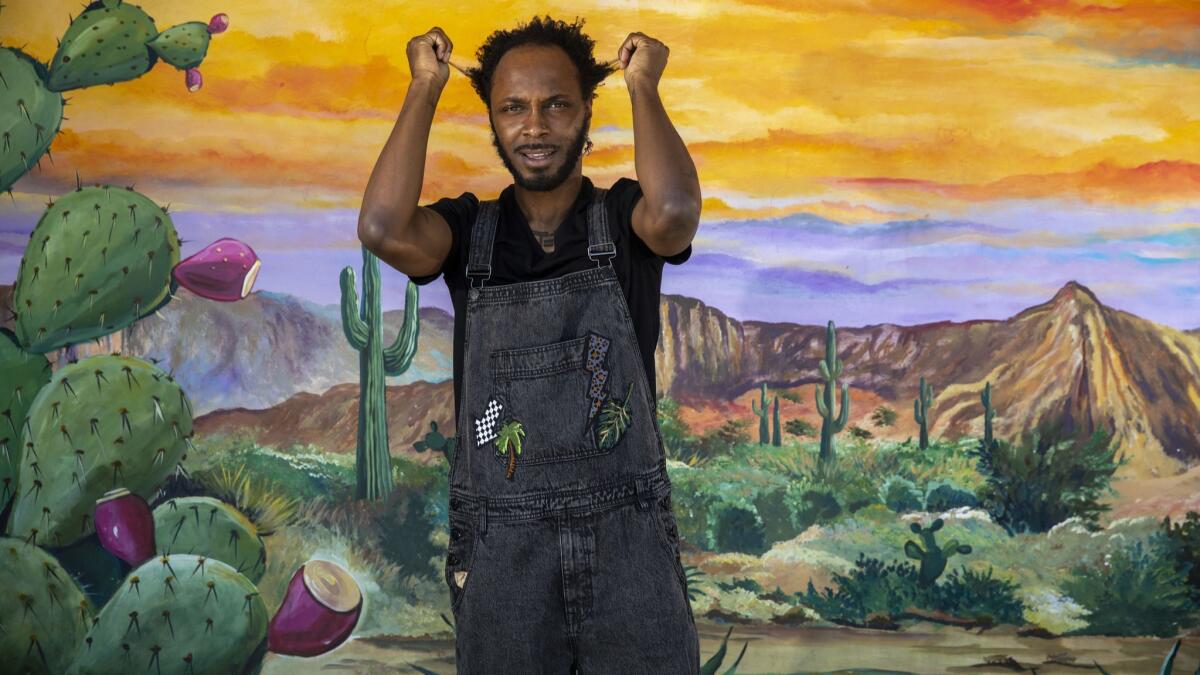

L.A. rapper JPEGMAFIA lashes out at the right and the ‘fake-woke’ left. Just don’t call it ‘trolling’

By August Brown

In the pantheon of current Republican government figures that Air Force veteran and hip-hop artist JPEGMAFIA despises (and it’s pretty much all of them), Rudy Giuliani holds a near and dear place in his loathing.

The 28-year-old rapper (born Barrington Hendricks) was raised in New York before decamping to Baltimore and now Los Angeles, and memories of the former mayor’s policies still boil Hendricks’ blood.

‘I can’t stay completely silent’: Jason Isbell looks inward in examining a ‘White Man’s World’

By Randy Lewis

Singer-songwriter Jason Isbell grew up in Green Hills, Ala., often hearing sentiments coming from his radio extolling the virtues of the good old days, of small-town America, of times that seemed simpler and happier through the rear-view mirror of history.

He took a different tack while writing songs for his acclaimed 2017 album “The Nashville Sound.” Several songs broached topics that are exceptionally touchy for many in country’s predominantly white, rural audience, and even more fearsome for radio programmers who try to avoid controversy at all costs.

The most noteworthy may have been “White Man’s World,” in which Isbell didn’t overtly rail against perceived injustices. Instead, he raised questions about his own life experience, about the privileges he’s enjoyed, where those privileges came from and who paid what price to create them.

California Sounds: L.A. artists rage and wrestle with politics and policy in the age of Trump

By Randall Roberts

Kendrick Lamar and YG are two of the best known contemporary Los Angeles music artists speaking out on social issues, but they’re part of a string of incendiary songs lobbed the administration’s way.

Other local artists making political music in their own unique ways include Dead Sara, Nik Frietas, Niña Dioz featuring Lido and Ceci Bastida, and Charles Lloyd and the Marvels featuring Lucinda Williams.

Beyond outrage: Australia’s Stella Donnelly mixes the personal and political with humor

Tense times call for tense songs, and Stella Donnelly has a few. See “Boys Will Be Boys.”

The single, which introduced the Australian artist to the pop world, goes deep on rape culture with verses that begin by documenting an individual story, in this case one belonging to Donnelly’s friend, and then widen out to encompass victim-blaming and the lifelong effects of trauma.

As one may imagine, it’s an intense listen. “Try playing it,” Donnelly said while in Los Angeles recently.

To Hurray for the Riff Raff’s Alynda Segarra, the personal is political

By Randy Lewis

Given her tumultuous history, Hurray for the Riff Raff’s Alynda Segarra probably couldn’t be an apolitical musician even if she wanted to. Which she admittedly doesn’t.

To the 32-year-old artist, speaking out with her music is as much a part of her DNA as her Puerto Rican heritage and her ingrained affection for New York and New Orleans.

“This is very real to me,” she says. “Politics was never something I felt was far away from me in daily life. The actions and choices made by people in power affected my future and those of the people around me. I was drawn to punk rock because I wanted to be around visionaries.”

Among the group that helped shape her vision were not only New York punk and hip-hop artists, but musical predecessors including Woody Guthrie, Patti Smith, David Byrne and Bowie.

“I love people who are not afraid of being seen as naive, they’re not afraid of thinking big, or worrying that things are changing too rapidly,” she says. “We have to try to change things as much as possible — we can’t just settle for things being the way they are.”

Review: Before ‘Hamilton,’ 100 years of American music theater and how it’s told the story of who we are

By Mark Swed

“Hamilton” didn’t come out of nowhere. For the last century, American music theater has been struggling with how exactly to represent our national character on stage, and with who we are. It’s a long story.

Consider that a remarkable centennial few are paying attention to is the premiere of the first meaningful American opera to have any real national success: The Metropolitan Opera’s production of Charles Wakefield Cadman’s “Shanewis (or The Robin Woman).” The 1918 opera is about a Native American singer who leaves her reservation in Oklahoma to study voice with a Santa Monica socialite at a “bungalow by the sea” (I’m not making this up).

ALSO

The Age of Hip-Hop: From the streets to cultural dominance

Days of rage and wonder: How 1968’s cultural shifts changed everything

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.