Beverley Thorne: man of steel

- Share via

Shortly before 7 a.m., Beverley Thorne stepped out of his home in Kona on the Big Island of Hawaii. A roll of drawings under his arm, the 85-year-old was off to meet the contractor on one of his new projects: a rectory under construction at Christ Church Episcopal in nearby Kealakekua.

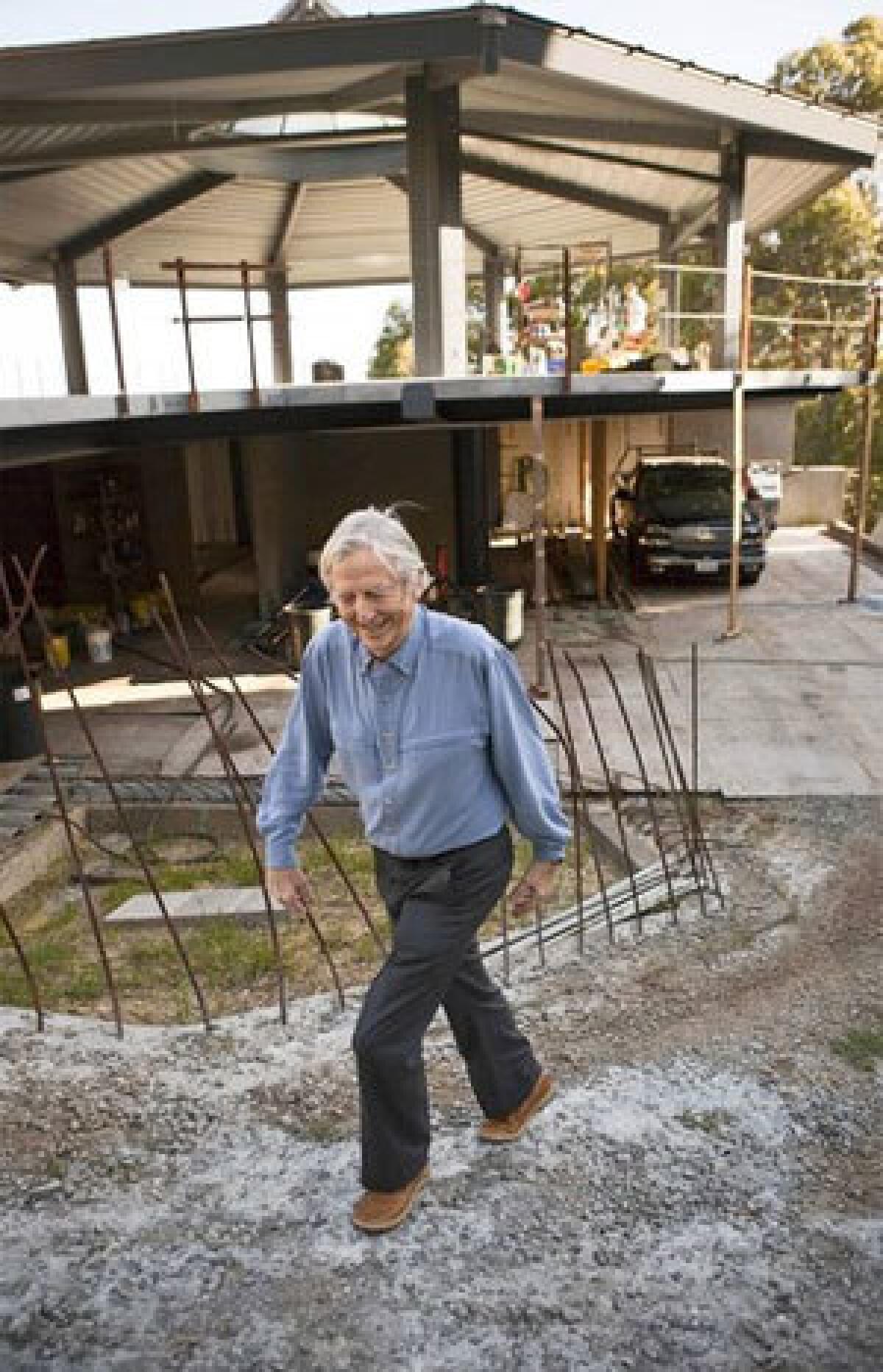

A few weeks later, Thorne flew with his fiancée to Oakland, where on a precipitous slope he is constructing the Millennium house, a 4,000-square-foot octagonal epic scheduled to be completed next year after more than a decade of planning and tweaking.

But perhaps his biggest distinction is one that he is much less eager to talk about: Thorne is the last surviving architect of the famed Case Study House program.

From 1945 to 1966 in his Arts & Architecture magazine, John Entenza published plans for three dozen houses and apartment buildings, all intended to be cutting-edge prototypes for modern living. Among the Midcentury notables chosen for the program: Richard Neutra, Charles and Ray Eames, Pierre Koenig, Craig Ellwood and, in later years, Thorne.

“I never met Entenza. It was all done by mail,” Thorne said. “That Case Study group was mostly from L.A., so the few of us who were from Northern California were considered strange birds.”

Completed in 1963, Thorne’s Case Study House No. 26 was a steel-frame home in the Marin County city of San Rafael. Though some Case Study plans were never realized, Thorne’s design got built thanks to a friendly competition between U.S. Plywood Corp. and Bethlehem Steel. Each company had boasted that it could build a less expensive house, so they footed the bills for two houses.

“I don’t think the competition was followed through in the financial sense,” Thorne said, “but we did beat them on framing, as our design was all pre-fab.”

Thorne’s house, perched along a hillside, is a spacious, four-bedroom home spread across one floor. A carport sits above, at street level. To lift its steel frame into place, a crane and crew needed only eight hours. Bolting and welding its various elements into permanent position took only eight hours more. Thorne, who had taken a welding course after he had graduated from the UC Berkeley architecture department, oversaw every move.

Floor-to-ceiling glass doors and windows filled out the frame, offering views beyond the 800-square-foot deck to what had been, more than 40 years ago, undisturbed chaparral in the distance. Today the design still stands, intact.

Early triumphs

Beverley Thorne first made a splash in the Bay Area in the mid-1950s when he designed a spectacular house for the legendary jazz pianist Dave Brubeck. Built atop a ridge high in the Berkeley hills, Thorne cantilevered wings of the home. One wing floated 16 feet off the ground.

“They had six children, and Olly, Dave’s wife, told me she didn’t want to run up and down stairs after them,” Thorne said, “so I kept building out.”

The result was so breathtaking that when Ed Sullivan did a show featuring the Brubeck Quartet, it was filmed at the house. Later, the Brubecks moved east to Wilton, Conn., and Thorne built them an even larger steel-framed house, which the couple still live in today.

Thorne estimated that he has designed upward of 200 houses in a career spanning more than five decades. Most, if not all, are on steep hillsides and are built out of steel, a material the architect fell in love with early on.

“Back then, a wooden beam was only 24 feet long, where its steel counterpart could be 60 feet, even longer with proper welding,” Thorne said. “That gave me so much more freedom.”

It was the ingenuity of his frames that allowed Thorne to perch so many light-filled homes securely and airily on steep cliffs.

“He likes to celebrate how structures float in gravity,” said Pierluigi Serraino, the author of the recent “NorCalMod.” “It was always a heroic gesture.”

Thorne’s genius, however, remains mostly uncelebrated — in part, a conscious choice. After changing his name to David Thorne and winning so much publicity from the first Brubeck house, the architect worried that such exposure would distract him, even blur the three-dimensional sense of space he’d developed as a fighter pilot at the end of World War II. He also remembered his close college friend, Donn Weaver, struggling to shake off the shadow of his father, noted painter Rene Weaver.

So, in the mid-1960s, not long after his inclusion in the Case Study House program, the architect decided to retire David Thorne.

“I went into hiding,” he said.

He reclaimed Beverley, his baptized name, and became a loner again. Relative anonymity would keep his work honest, Thorne believed, and would give his children the freedom to develop however they liked.

His career never reached the same heights as before.

Steely determination

In the end, Thorne shared his talent mostly with three sons: David, a landscape architect; Stephen, a commercial architect and inventor; and Kevin, also an architect. They provided the inspiration when it came to adding a spectacular steel-and-glass addition to Thorne’s house in the Oakland Hills, where he divides his time with Kona. The result was a living room 60 feet long by 22 feet high, with towering walls lined in an unlikely fashion with redwood shingles.

“We didn’t have access to cranes,” he recalled. “My boys and I just used ropes and slung the giant frame together.”

Today, Thorne’s love affair with steel is as strong as ever. The 1,500-square-foot project in Kona, built to house the church’s pastor, has a steel frame for the clerestory windows above the lower roof line. But the use of steel there, unusual in Hawaii, pales in comparison to the critical role it plays in Thorne’s Millennium house, the Oakland project whose name stems from the fact that Thorne’s initial designs date to 2000.

Designed for client Edward Baker, the multilevel home is supported by a crisscrossing mass of steel beams.

“It had to be engineered that way to hold up the reinforced concrete floors,” Thorne said, adding that Baker wanted to park his 1957 Porsche Speedster in the living room.

For a man whose houses have dared the unimaginable, Thorne is reluctant to discuss his own prowess or place in history. He simply works every day at a small drawing table set up in the screened-in lanai at the front of his Hawaiian home.

“I don’t look at my old houses very often,” he said. “You always know they could have been done better, and it really hurts you to see that.”

He’s reluctant to talk about the Case Study program too.

“Most of those fellows are long gone. It’s kind of spooky that they are,” he said with characteristic understatement, perhaps unaware that with the death of Kemper Nomland Jr. in December, Thorne is the last survivor in a list that contains fewer than three dozen names. At 85, he may move more slowly than in years past, but he still jumps up to receive a call from the contractor on the Kealakekua project. And in an instant, his buoyant smile returns.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.