The evolution of my relationship with wine is an apt metaphor for my approach to food journalism at large.

- Share via

One of the most valuable things I learned in college was how to uncork a bottle of wine. But it was a lesson that happened at great expense — my utter humiliation.

Sophomore year. First off-campus apartment. Found a roommate who was, refreshingly, enrolled at the local community college and not at stressed-out Cal like me. One evening in our kitchen, I admitted that I didn’t know how to use a corkscrew bottle opener. She laughed in my face — chortled with glee, more like it.

“You don’t?”

How the hell should I? I was just 19. There were no courses available for this task in the UC apparatus at the time — at least that I was aware of. Chastened, I realized that nearly every time I’d been around wine it was boxed or in twist-cap form. Anytime a bottle required uncorking, someone capable was usually nearby to handle it.

From Times editors Laurie Ochoa and Daniel Hernandez: There’s no better place or moment for eating and cooking than in Los Angeles right now.

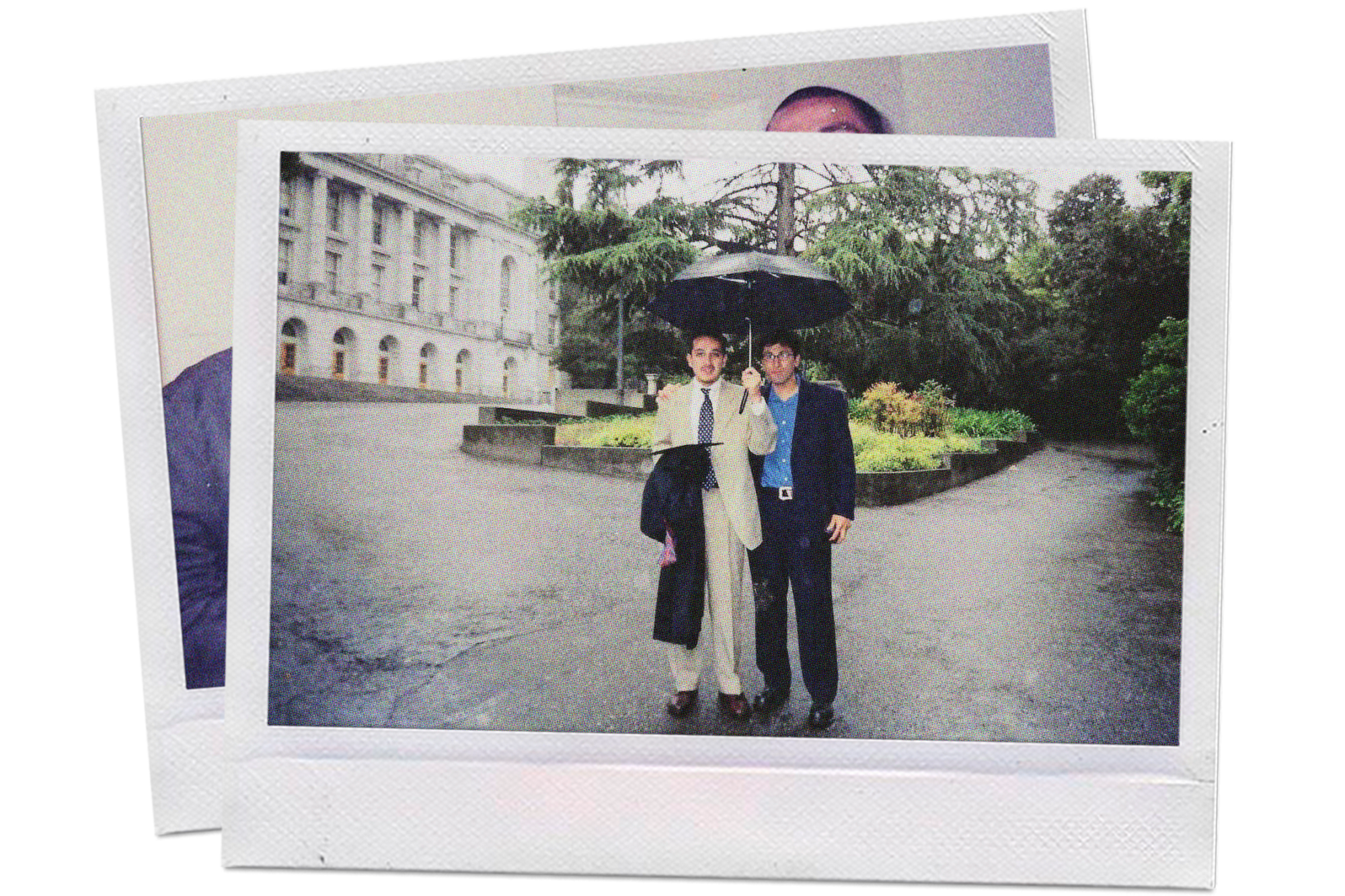

My roomie set out to teach me. I failed a lot at first. A couple of times my fingers got pinched in the corkscrew opener’s arms, cut open and bled. A year later my brother Ernesto moved in with me after getting out of the Army, and with his expertise, my wine-bottle-opening skills ratcheted up and matured. When he found his own apartment in San Francisco, he started home-brewing beer. We soaked in the Mission District’s culinary ferment: esoteric IPAs of every variety, dinners at neighborhood spots with modest corkage fees for paper-bag-wrapped wine bottles brought in from the chill of a corner liquor store.

Two decades later, I am a devotee of California red blends, California Sauvignon Blancs, Chilean blends, the Merlots of Mendoza, Argentina, and Chiantis that echo with the notes of the heirloom grapes of Los Angeles. When a cheap bottle of red is all that’s handy and I want it to last, I make myself a casual calimocho-style spritz, without cola: wine over ice, Topo Chico mineral water, fresh lime juice and a handful of smacked mint or rosemary leaves. (You’re welcome!)

This evolution in my relationship with wine is an apt metaphor for my theory on food journalism at large. These days, there may be more culinary schools, wine-making programs, food-writing courses, tours and conferences than ever before. Yet there is still no concrete path or certifying checklist for success in this industry. And there should never be.

In food media, as in life, everyone is an outsider until they’re an insider.

The record supports this truism. Jonathan Gold, preeminent restaurant critic of his generation, studied the cello and music history at UCLA and wrote some of the earliest mainstream articles on L.A. gangster rap before turning to food journalism full-time. Critic Gael Greene, who died in November at 88, identified simply as a reporter before legendary editor Clay Felker asked her to start writing about restaurants.

“I felt that I was an impostor,” she told an interviewer in 2008. “I definitely thought they were all going to figure me out very quickly. So that is why I said to myself, ‘Well, I’ll just go into this like a reporter; who, what, why, where, when.’”

Bingo.

Reporting is the magic key to writing about food, and reporting happens to be one of my strong suits. I’ve covered breaking news on the police beat. I’ve written about higher education, local politics, artists, street culture and architecture. Ask me anything about the U.S.-Mexico drug war; I’ve been a conflict and politics field correspondent in the most troubled parts of Mexico and in South America. I once wrote a column for the stodgy, stubbornly offline magazine Art in America. I was even a fashion writer for a bit, with a front-row seat at Mexico City Fashion Week.

Come to think of it, failure is one of the defining features of food culture.

And of course, while living there, I dove into the universe of Mexican cuisines. I suppose that’s when I started to develop my armory as a food journalist. Every state, every town in Mexico has its own food totems. I became hooked. Tamales, quesadillas (which can come without cheese!), tacos, sopas, guisados, tortillas, native ingredients like chocolate and corn, rustic fermented beverages, even Mexican hamburgers. Just when I thought I could wrap up a subject in my brain, there was another leaf to turn over, another mystery to consider.

One day, the video producers at Vice Media looked me up and down, realized I spoke English and Spanish equally, and asked: “Have you ever thought about being on camera?” Actually, I hadn’t. But another maxim that’s guided me in life is to never say never to new platforms to tell a good story. Next thing I knew, I was whisked off with a camera team to the four corners of Oaxaca, where we made one of the most successful video series in Vice history: “Munchies Guide to Oaxaca.” Before long, Andrew Zimmern’s people called and asked me to appear on “Bizarre Foods.” Then Netflix called and asked me to talk on “Taco Chronicles.”

Through video, audio, long-form and short-form, journalism is my calling.

In this role as Food editor, my approach is to embrace more fervently than ever the rule that there is no such thing as a dumb question. My colleagues Laurie Ochoa and Betty Hallock, as well as our staff writers and columnists, are as a whole more versed in the food-culture metadata than I am. I follow their leads, happily. I ask them my dumb questions. Sometimes their eyes widen when I reveal an especially acute knowledge gap. I smile. “Show me,” I say. “I want to hear more.” “I’d love to try that.”

There’s no script to this stuff. To lead is to constantly learn, right?

Everything I’ve learned about food throughout my life has been through observing, asking, listening, tasting and attempting recipes at home. With many — many — failures at said endeavors.

I wasn’t raised by a chef or a cookbook author or in a restaurant. My dad spent a great sum of his teens and 20s picking fruits and vegetables in California’s Central Valley. My mother makes excellent tortillas de harina and frijoles de la olla, staples of a household of border subjects. Beyond that, I grew up, perhaps as many of you did, on American processed foods and fast-food kids meals.

I’ve never worked in a restaurant or taken a cooking course, either. Everything I’ve learned about food throughout my life has been through observing, asking, listening, tasting and attempting recipes at home. With many — many — failures at said endeavors.

I relish these failures. Come to think of it, failure is one of the defining features of food culture. A cocky alpha chef with media savvy is usually just masking a litany of scars from missteps and culinary miscarriages. Restaurants open with bells and whistles, then might shutter quietly within a handful of months. Home kitchens are torched in poor attempts at frying, say, a whole Thanksgiving turkey. And what is baking with success but a process of elimination of bad results?

So many of the integral dishes of L.A. — Thai boot noodles from Sapp, Mariscos Jalisco’s tacos dorados de camarones or Langer’s hot pastrami — may have come from elsewhere, but that makes sense. Most of us Angelenos come from someplace else even if we were born here.

As we retool and relaunch the food coverage at the Los Angeles Times, I want to ask our readers and audiences to embrace their knowledge gaps and their food failures. Impostor syndrome is a myth we’re better off retiring. In truth, we are all, each one of us, an impostor to the food-obsessed self that once existed only in one’s ambitions. Or, as in my case, in digits sliced by a corkscrew bottle opener.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.