Eyewitness to Watts riots won’t give in to discouragement

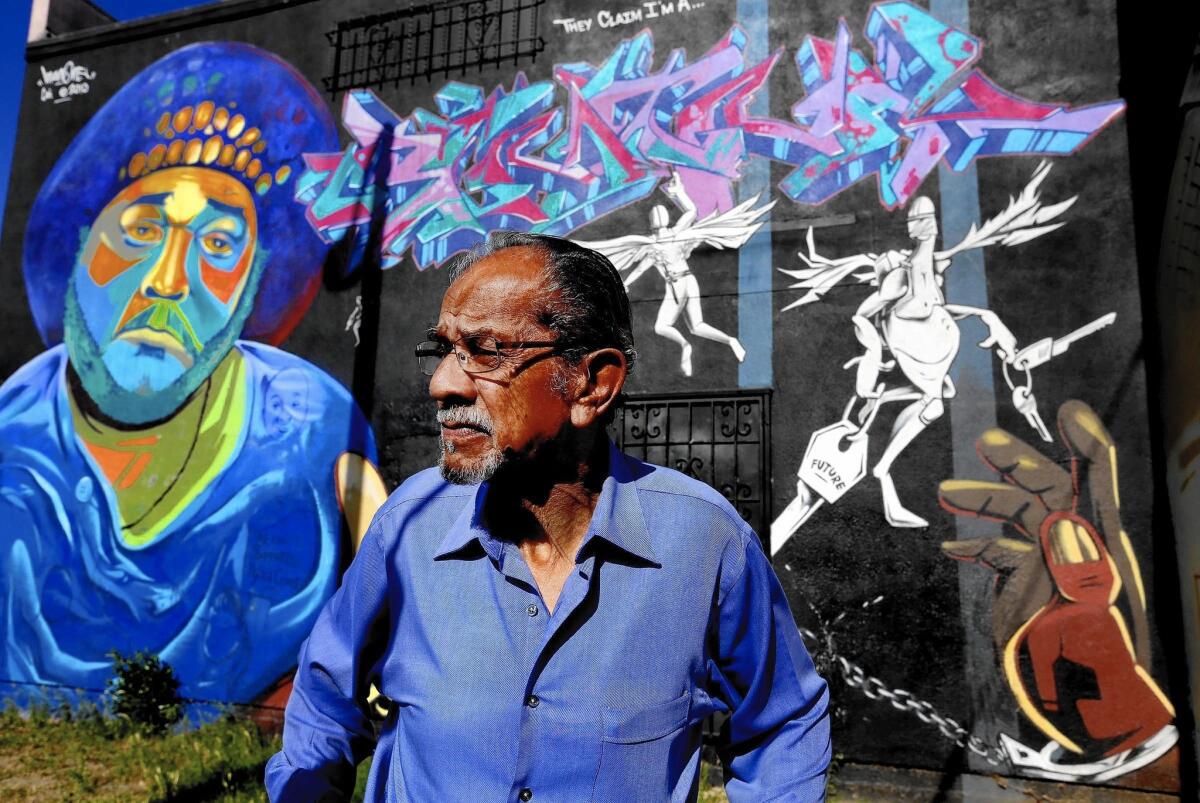

Larry Aubry outside the Southern California Library at 61st and Vermont. In 1965, Aubry, a probation officer, witnessed police shooting at looters on the site, which at the time was an appliance store. Aubry’s years of columns for the Los Angeles Sentinel are part of the library’s collection.

- Share via

Larry Aubry and I met at Century and Western, near where, a week earlier, two children and an 18-year-old woman were shot in what has been a bloody summer in South Los Angeles.

City officials and community leaders have been strategizing to try to restore calm, but that’s hard to do when the underlying causes remain much the same decade after decade.

Five of those decades ago, Aubry was a 32-year-old probation officer and an idealist and activist by nature, and he knew plenty about the anger and sense of injustice that had been simmering for a long time even then. When Watts exploded it did not come as a surprise to him.

The city was starkly segregated. The schools on the south side were inferior. Unemployment was entrenched. Politicians were seen as indifferent, at best, and the police as racist.

So of course the neighborhood blew, the smoke rose, the looting raged, the National Guard marched in and the bodies piled up in six days of mayhem that began on Aug., 11, 1965, following the arrest of a black motorist.

A half century later, Aubry is 82, and in some ways, social and economic conditions are no better now in South Los Angeles than they were in 1965. The area has gone from mostly African American to mostly Latino, making recovery for black residents all the harder because of leadership shifts and loss of momentum.

If Aubry had become discouraged and walked away from the cause, fed up with 50 years of empty promises, you probably wouldn’t blame him.

But he hasn’t. He’s still engaged and still enraged. And miraculously, though he’s a realist, he’s still an idealist and activist who chooses to believe better days are coming.

“All the things I was concerned with, then and now, are not points of discouragement for me,” Aubry said. “They’re challenges.”

The restaurant at Century and Western, where we intended to chat, was too busy and loud, so Aubry suggested we move to 61st and Vermont, an intersection seared in his memory. A few days into the Watts riots, he had just dropped off a family member at a relative’s house near there when he heard gunfire in the vicinity of an appliance store.

“I came out cautiously and inched toward the corner,” Aubry said.

That’s when he saw several police officers shooting at looters.

“I’m telling you, they shot at these guys coming out of the store, and I saw the guys drop the stuff and run,” Aubry said.

He certainly didn’t condone looting and had been telling his young probation charges not to get caught up in that kind of thing, but Aubry couldn’t believe the police had opened fire.

That appliance store no longer exists. In its place, fittingly, is the Southern California Library, whose website describes it as a place to “research and put to practice the histories of … people working to create change.”

People such as Aubry, whose years of columns for the Los Angeles Sentinel are part of the library’s collection. Anyone is free to visit, study Aubry’s careful reflections and calls to arms on race, justice, leadership and community, and loot his best ideas.

“He was my best source,” said his daughter, Erin Aubry Kaplan, a journalist who began focusing on those issues after the 1992 riots. “He knows everybody, and it’s not just his generation.”

She said she bounces ideas off her father, trusts his judgment, and is amazed by his ability to keep believing positive changes are coming, if only because this is a resilient people who survived the theft of history and culture and came through slavery.

“He says discouragement is really dangerous,” says Aubry Kaplan, “because then you just unplug and turn away, and for him, it’s the worst thing any of us can do.”

Larry Aubry was born in New Orleans, moved west with his family as a kid, and found that Los Angeles had its own forms of segregation.

There were swimming pools he couldn’t swim in, restaurants he couldn’t dine in.

Aubry’s mother transferred him from all-black Jefferson High to nearly all-white Fremont High because she thought it was a better school. Aubry said he was petrified.

“There were signs out front that said, ‘No Niggers.’ The community and students were there with banners … and on the school grounds, tar babies were hanging in effigy.”

Aubry got through what he called a terrible experience, served in the Air Force, studied at UCLA and other colleges and was drawn to a career in service. He spent decades as a consultant to the human relations commission and was a school board member in Inglewood, where he lives.

Today he’s anything but retired. In addition to the column, Aubry is co-chair of the Black Community Clergy and Labor Alliance, whose activist causes align with his own.

Do we live in a more tolerant society today than we did when Watts erupted?

In many ways, yes, said Aubry, noting that an African American is in the White House.

But then again, we’ve just come through a year of controversial shootings of black men by police officers, in Los Angeles and beyond, reminding us that in 50 years the divide between cops and black communities hasn’t narrowed as much as we might have hoped.

“Some things are better, and it has to do with opportunities that opened up socially, economically and politically, and there’s no question about that. But it’s been confined to a relatively small group in the black community,” Aubry said.

He quotes a friend who once told him, “We got what we wanted, but we lost what we had.”

What it means to Aubry is that some black people moved up and out, but common purpose and a united front were lost in the process, and those who were left behind became all the more trapped by the conditions they were born into.

Aubry is willing to assign blame to just about everyone and everything, from white people having social and economic advantages many aren’t even aware of, to poor blacks’ detachment from the wider civic culture, to under-resourced schools, to the crippling demise of manufacturing and aerospace jobs, to lousy leadership and black apathy.

“Black lives have always mattered, but black people don’t always act like black lives matter,” he said. “Some folks are so conditioned that they engage in behavior that’s … inimical to their own interest. It doesn’t make sense. Why would you keep the boot on your neck?”

What’s needed, said Aubry, is the kind of “sustained righteous outrage” that hasn’t existed since the 1960s. It’s not a riot he wants, but a social rebellion.

Fifty years after Watts, Aubry has to believe that it’s coming.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.