Ojai residents take stock of their blessings — and vulnerability — after surviving the Thomas fire

- Share via

Reporting from OJAI — Ojai residents knew an autumn like this would come. They were aware that the mountains that ring their isolated valley town were, like much of rugged Ventura County, vulnerable to wildfire.

They figured they were prepared.

But after the Thomas fire broke out eight miles to the east on Dec. 4, it swept with breathtaking speed toward town and, within two days, had all but encircled Ojai. Firefighters cut containment lines within a mile of the yoga studios, organic restaurants and boutiques along the colonnaded main drag, and forecasts called for searing winds of up to 70 mph that would blast flaming embers in all directions like tracer rounds.

“We were surrounded by raging fires,” recalled Victoria Adam, a wine tasting room co-owner who is on the board of directors of the Ojai Chamber of Commerce. “I thought, ‘Oh my God, Ojai’s going to burn down.’ ”

One need not be part of Ojai’s spiritual community to consider it a miracle that the 4-square-mile town of about 8,000 people escaped largely unscathed from a blaze that destroyed more than 750 homes in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties, killed two people and eventually grew into California’s biggest fire on record.

Now that the shock of advancing flames has worn off, residents are beginning to take stock of their blessings — and their vulnerability.

Looking back, Tim Dewar, publisher of the Ojai Valley News, said Ojai was spared because of human decisions and geological quirks.

He credits the “foresight of fire authorities to strategically position units” due to red flag warnings, the hard work of thousands of firefighters, and “the efforts of residents including farmers and ranchers who used their own equipment to cut fire breaks and move people to safety.”

But the mountains, he says, also played a role.

Unlike most California ranges, which run north-south, Ojai sits within a transverse range running east-west. Those mountains give Ojai its distinctive backdrop — especially as they turn pink and purple during the city’s memorable sunsets. But they also “blocked a significant amount of the powerful winds that other areas suffered,” he said, allowing firefighters to get the upper hand.

Few residents had better views of the encroaching infernos than the mystically inclined artists, authors and gurus at a hilltop spiritual center in Ojai called the Krotona Institute of Theosophy, which took its name from Crotona, Italy, home of an ancient school led by the Greek philosopher Pythagoras.

Its founders moved to Ojai — a bucolic location they believed was awash in positive vibrations and guardian spirits — in 1924 in hopes of passing on ancient philosophical notions to future generations of reincarnated souls.

“The old-time Theosophists used to say there were ‘devas,’ or angelic forces, in these hills who would not let anything ever happen to Krotona,” said Robert Ellwood, former director of USC’s School of Religion and a scholar in residence at the Theosophical Institute. “I might not say that, but this much is certain: Firefighters did a heroic job.”

On Monday, the Thomas fire was 92% contained, just burning in hot spots far from town. But Ojai isn’t out of trouble yet.

A worry now is that winter storms could trigger surges of muck and fallen trees down canyons stripped of their binding vegetation by the fire.

The first major storm of the year moved into the Ojai Valley area Monday morning, with National Weather Service forecasts calling for four to seven inches of rain in the surrounding mountains over the next 48 hours. A flash flood watch remains in effect from Monday evening through Tuesday evening.

“Usually, the first year a burn area sees rain is the most critical in terms of potential flooding and debris flows,” said Stuart Seto, a National Weather Service meteorologist based in Oxnard. “The Thomas fire area is one of the most vulnerable.”

Past floods caused extensive damage when storm drains and drainage ditches overflowed to create vast lakes in city streets.

Another concern is Matilija Dam, a concrete arch curving across southern-facing slopes a few miles northwest of Ojai. It is one of the most dangerous watersheds in the United States because the canyon walls on either side are so steep and prone to heavy rains, Ventura County flood control authorities said.

Built in 1947, the dam killed off steelhead runs in the Ventura River and gradually filled with silt. It currently operates at reduced capacity because it could not otherwise meet state seismic and safety requirements, authorities said.

Local groups have for years been searching for the roughly $80 million needed to tear down the dam, which has nearly reached its capacity of 9 million cubic yards of sediment.

“If substantial rain comes down, I expect sediment and debris to flow over the spillway,” said Peter Sheydayi, deputy director at Ventura County Watershed District. “We’re in the midst of working on risk reduction measures such as installing debris flow sensors to determine whether evacuations are needed.”

“The dam itself,” he added, “is safe.”

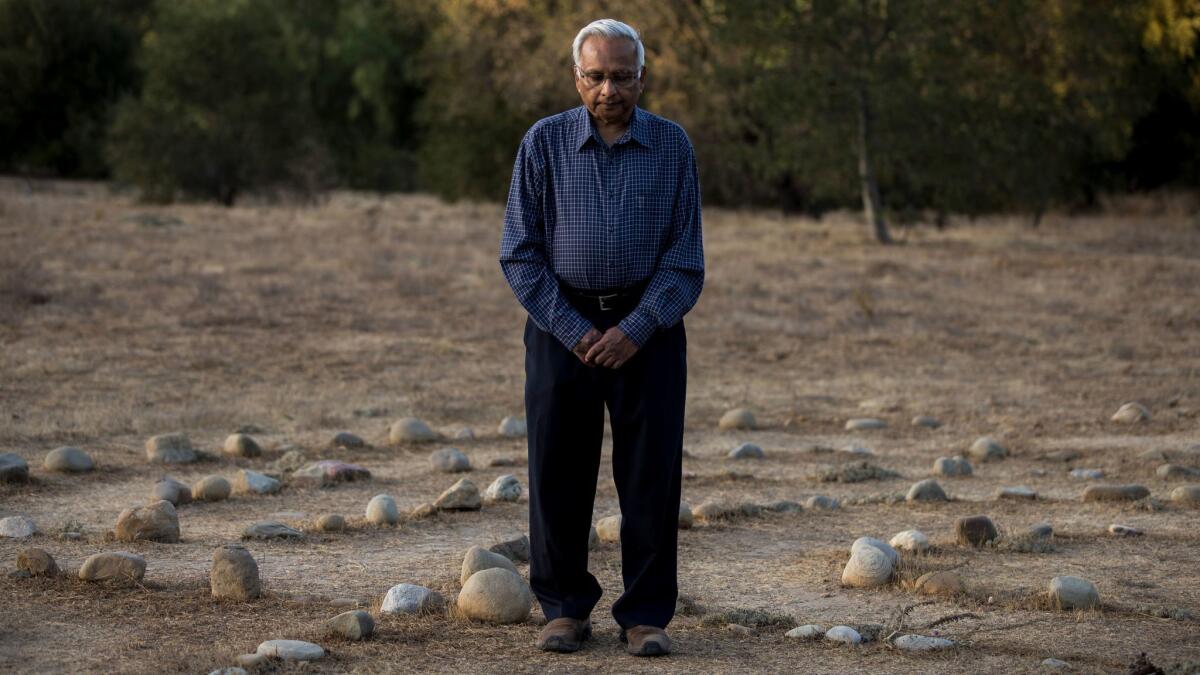

Paul Jenkin, an environmental activist in Ojai and founder of the Matilija Coalition, a nonprofit group dedicated to restoring the Ventura River, is not so sure. Surveying the structure from an overlook and shaking his head in dismay days before the rain, Jenkin said, “Obsolete dams like this one are ticking time bombs.”

Officials say there are roughly 8 million cubic yards of debris behind the dam now. “So the next big storm will push huge amounts of mud and water over the top, overwhelming bridges, culverts and roads below,” Jenkin said.

The fury of the Thomas fire has left idyllic Ojai a community at odds because it exposed the risk of living in an isolated mountain valley with few roads in and out.

Even as resort staffers sweep up ashes and change bedsheets and mattresses that reek of smoke, local factions are arguing over proposals for improving emergency planning, and avoiding communication breakdowns and power failures.

And the Ojai City Council has to defend its decision last year to let lapse a local sales tax that had funded its tourism bureau, which closed in October, a month before terrifying images of fires marching into the Ojai Valley and devouring homes, trees and brush were captured live on TV.

Ojai’s City Council decided the tourism bureau wasn’t necessary, Ojai Mayor John Johnston said.

Adam, who co-owns the wine tasting room, disagrees. Tourism has tapered off since the fire roared past town, she said, and sales in many local businesses are 50% what they usually are at this time of year.

Some hotels including the Ojai Valley Inn, the largest economic driver in town, expect to remain closed for another week or so. Most of the popular hiking trails in nearby hills and mountains suffered extensive damage and will remain closed indefinitely, officials said. And from Ojai’s town square, charred ridgelines dominate the panoramic view.

“Our trees are still green, our sky is still blue and we still have our pink moments when the sun goes down,” said Leslie McCleary, a spokeswoman for the Ojai Chamber of Commerce and a lifelong Ojai resident. “But if you’re looking for ugly, there’s lots of it around here. It just depends on where you’re standing.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

![Vista, California-Apri 2, 2025-Hours after undergoing dental surgery a 9-year-old girl was found unresponsive in her home, officials are investigating what caused her death. On March 18, Silvanna Moreno was placed under anesthesia for a dental surgery at Dreamtime Dentistry, a dental facility that "strive[s] to be the premier office for sedation dentistry in Vitsa, CA. (Google Maps)](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/07a58b2/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2016x1344+29+0/resize/840x560!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F78%2Ffd%2F9bbf9b62489fa209f9c67df2e472%2Fla-me-dreamtime-dentist-01.jpg)