L.A. now has a new tallest building. How it will fit into the fabric of the city is still open to debate

- Share via

Standing at the base of the Wilshire Grand, architect David Martin shielded his eyes to take in the scope of Los Angeles’ newest and tallest skyscraper.

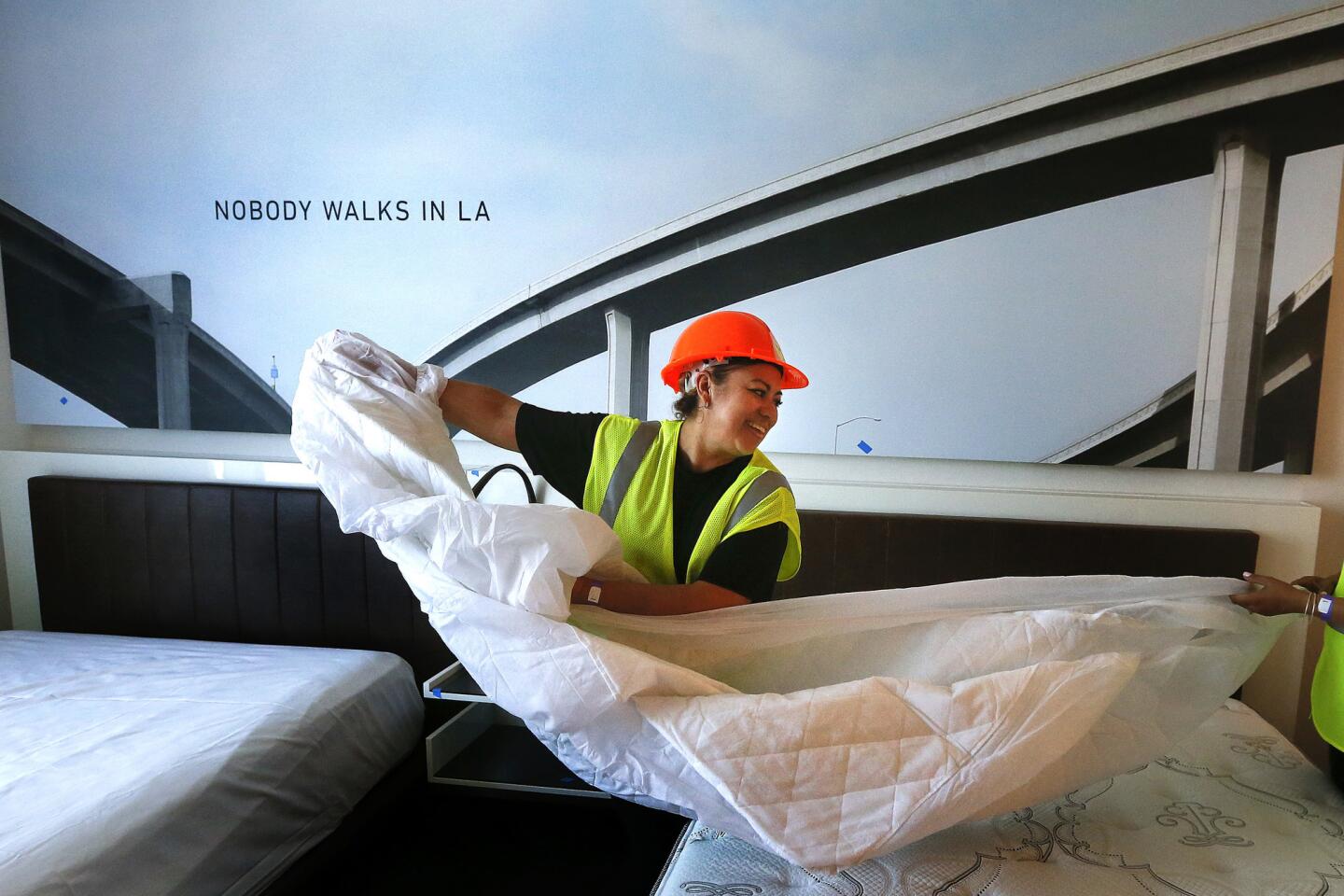

Eight years ago, this shimmering glass tower began its life in his sketchbook as an ink drawing and a splash of blue wash. Now, after four years of construction and $1.35 billion, it is debuting on the city’s stage. Guests have begun to arrive; tenants come later in the year.

The prospect leaves Martin a little nervous. The expectations for this building are high.

For all its 21st century detailing, the Wilshire Grand is a throwback to a time when Los Angeles dared to dream tall and for three decades — the early ’60s to the early ’90s — saw a fledgling skyline emerge above Bunker Hill, Century City and Westwood.

But such aspirations can be fickle. That boom, financed in part by Japanese capital, stalled amid an economic recession. Now 30 years later, this new tower rides a new wave of development rippling through downtown and outlying communities such as Hollywood and mid-Wilshire.

Driven by Chinese and Korean investors, this prosperity reflects not only a shift in the world economic order but also a renewed faith in Los Angeles’ potential on the edge of the Pacific Rim. (In 2015, South Korea was Los Angeles’ No. 3 trading partner, with two-way trade totaling $23.7 billion.)

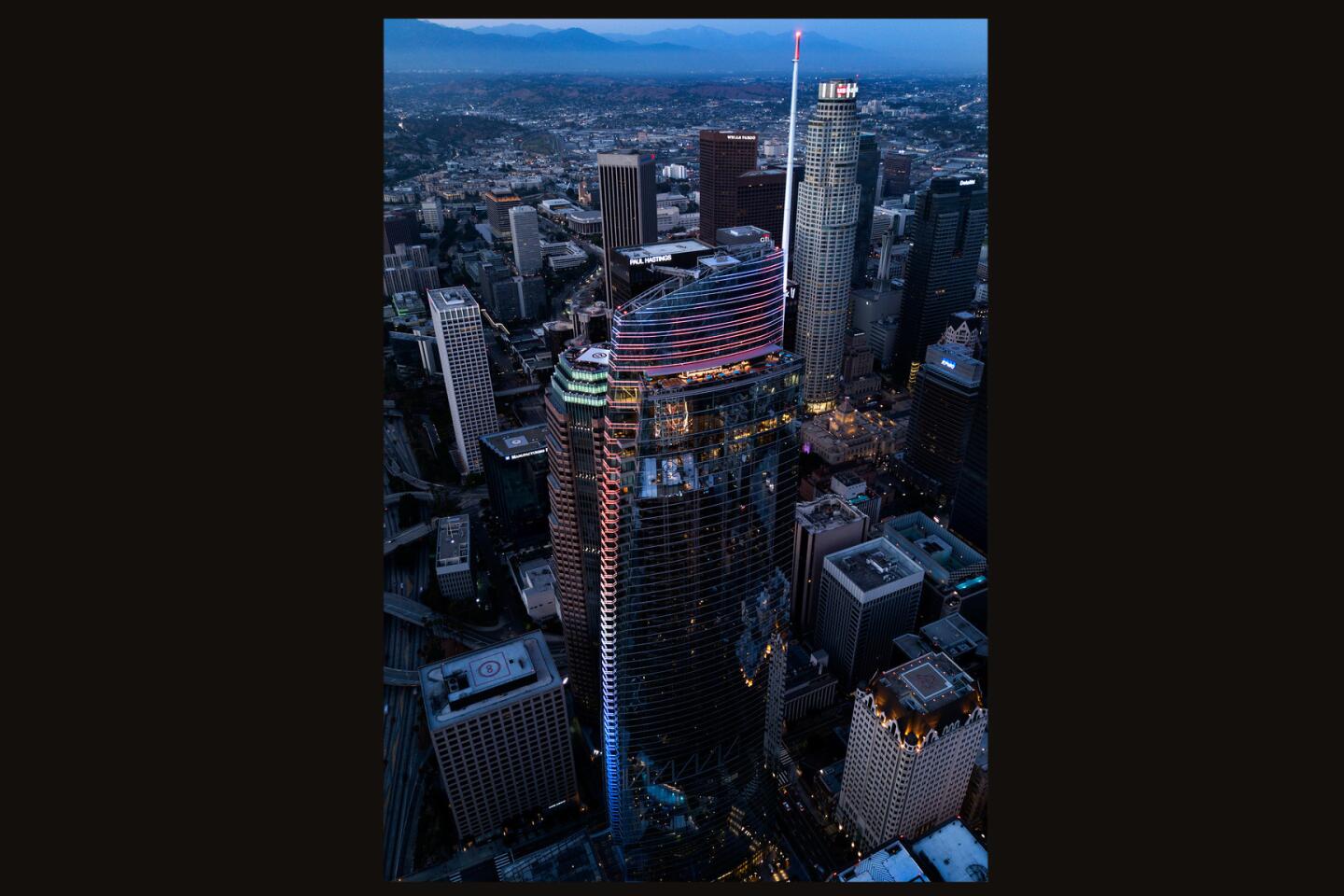

When Korean Air, owner of the Wilshire Grand, lighted the building’s crown with the red, blue and white swirl of its logo, it captured that historical sweep. The airline’s chairman, Yang Ho Cho, first visited downtown Los Angeles on his honeymoon in 1974 and was told to be careful if he went out after dark.

Today he expresses the hope that this building will be an icon for the city as well as a symbol of pride for its Korean community.

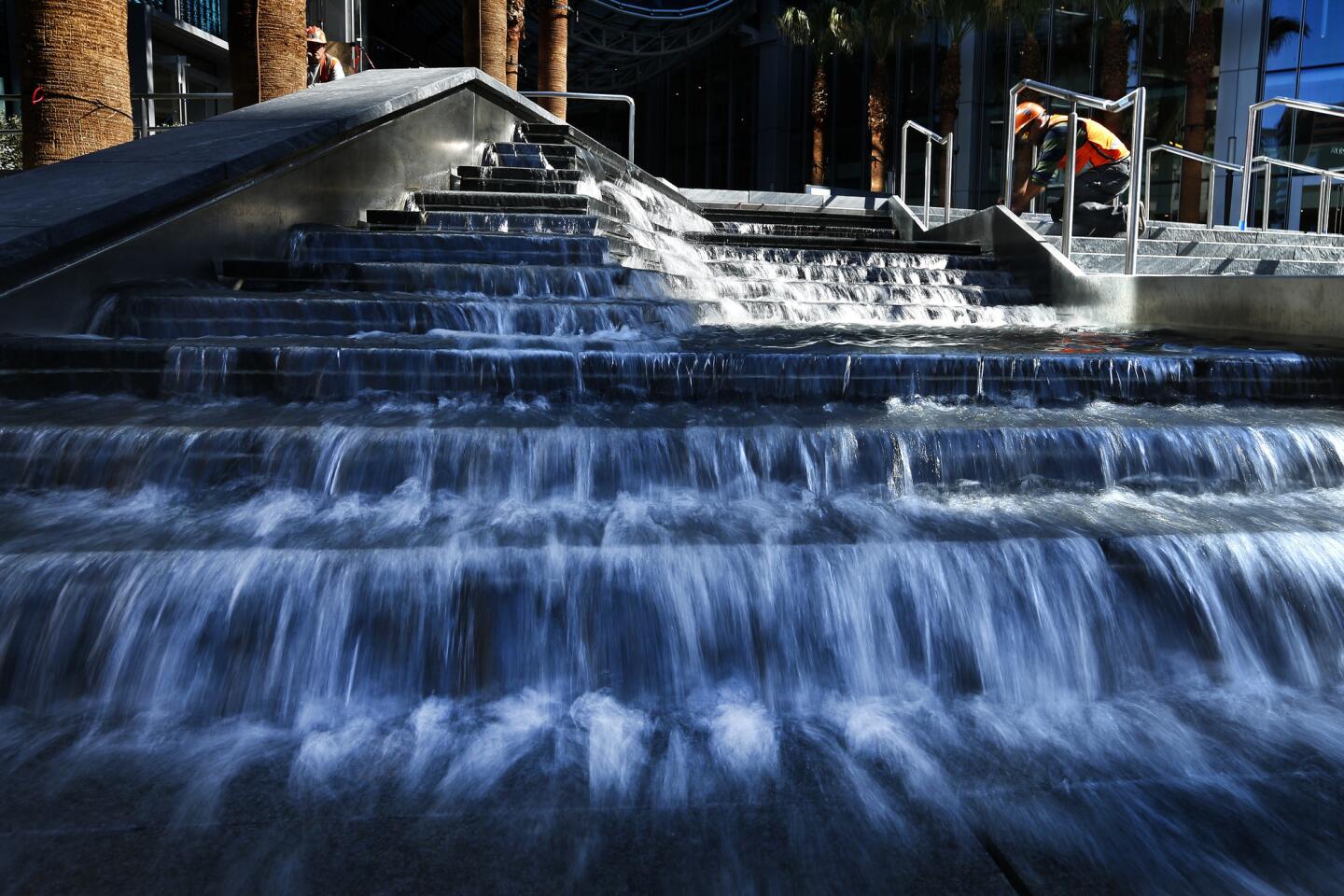

But on a late May afternoon, Martin wasn’t taking a global perspective. Wandering out onto the pool deck overlooking 7th Street, his concerns were more immediate. The amplified strains of a violinist drifted from a distant sidewalk.

The Wilshire Grand has represented for him a lifetime opportunity to build a downtown landmark, much as his grandfather did with City Hall and his father with such high-rises as the Department of Water and Power and the Arco Towers.

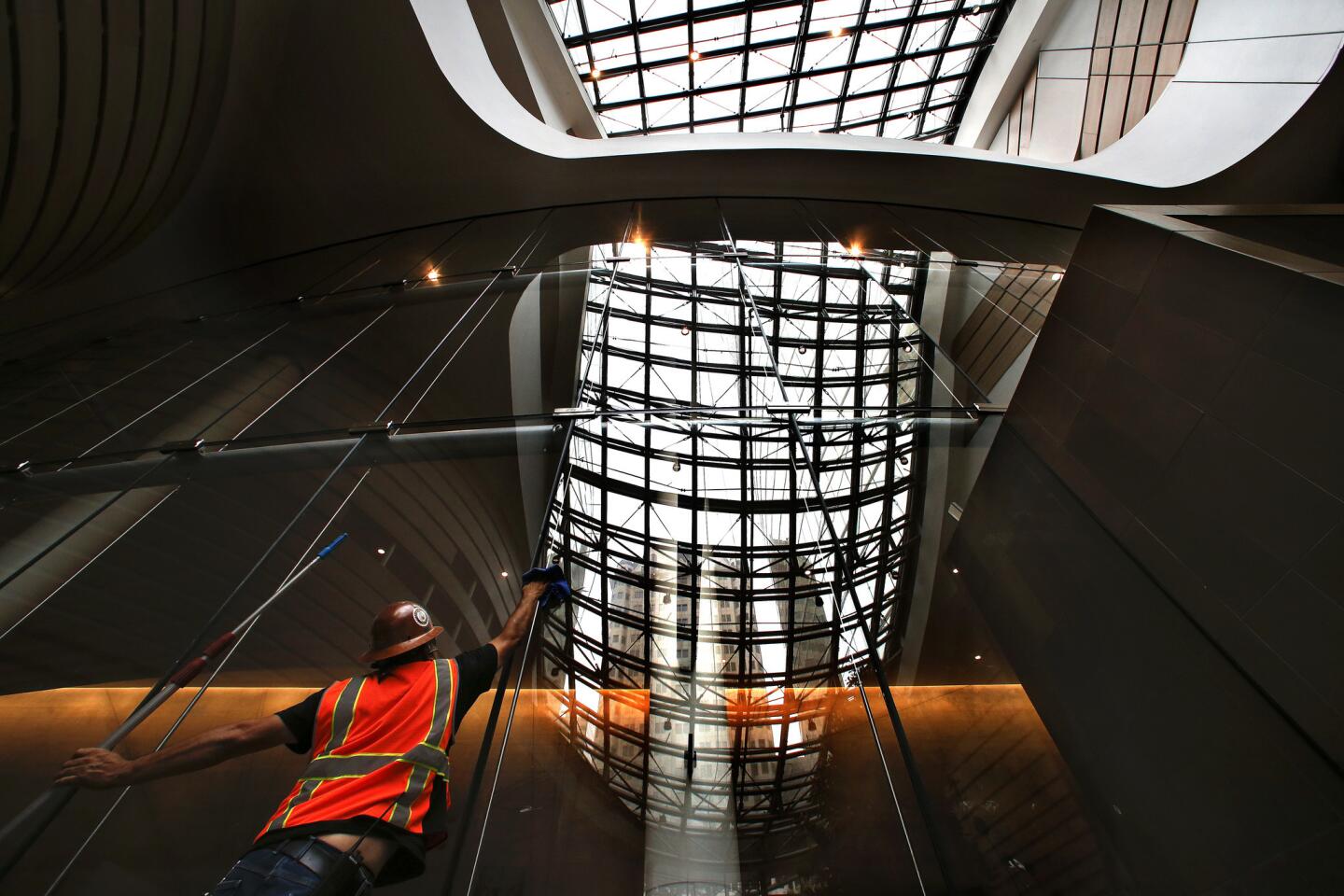

He spoke of the building’s parametric sloping, its reflectivity, the alignments between the indoor and outdoor spaces and the overhead “bones,” the seismic supports — and he anticipated the critics.

What does the Wilshire Grand offer the city, they will ask. Is it for the wealthy and privileged? Does it advance the science of engineering or a theory of architecture?

“I hope they all like the building,” he said.

::

Every tall building is a unique performance, a blend of grand effects and minute detail. Some strike a single note. Others try for a deeper, almost symphonic complexity.

The gesture might be old-fashioned, reminiscent of the early decades of the 20th century, a statement that speaks more to the egos of a few than the needs of the many.

But this is what cities do, no matter the expense or impracticality. From a distance, these structures declare their prowess and modernity by lifting themselves above the horizon like Oz, proxies in glass for ambition and power. From the sidewalk, they inspire passers-by to peer skyward, a remarkable feat when daily occupations compel many to look only ahead.

And in Los Angeles — not New York, not Chicago — the raising of these buildings is all the more remarkable in a region where downtown is a mere island in a vast suburban sea.

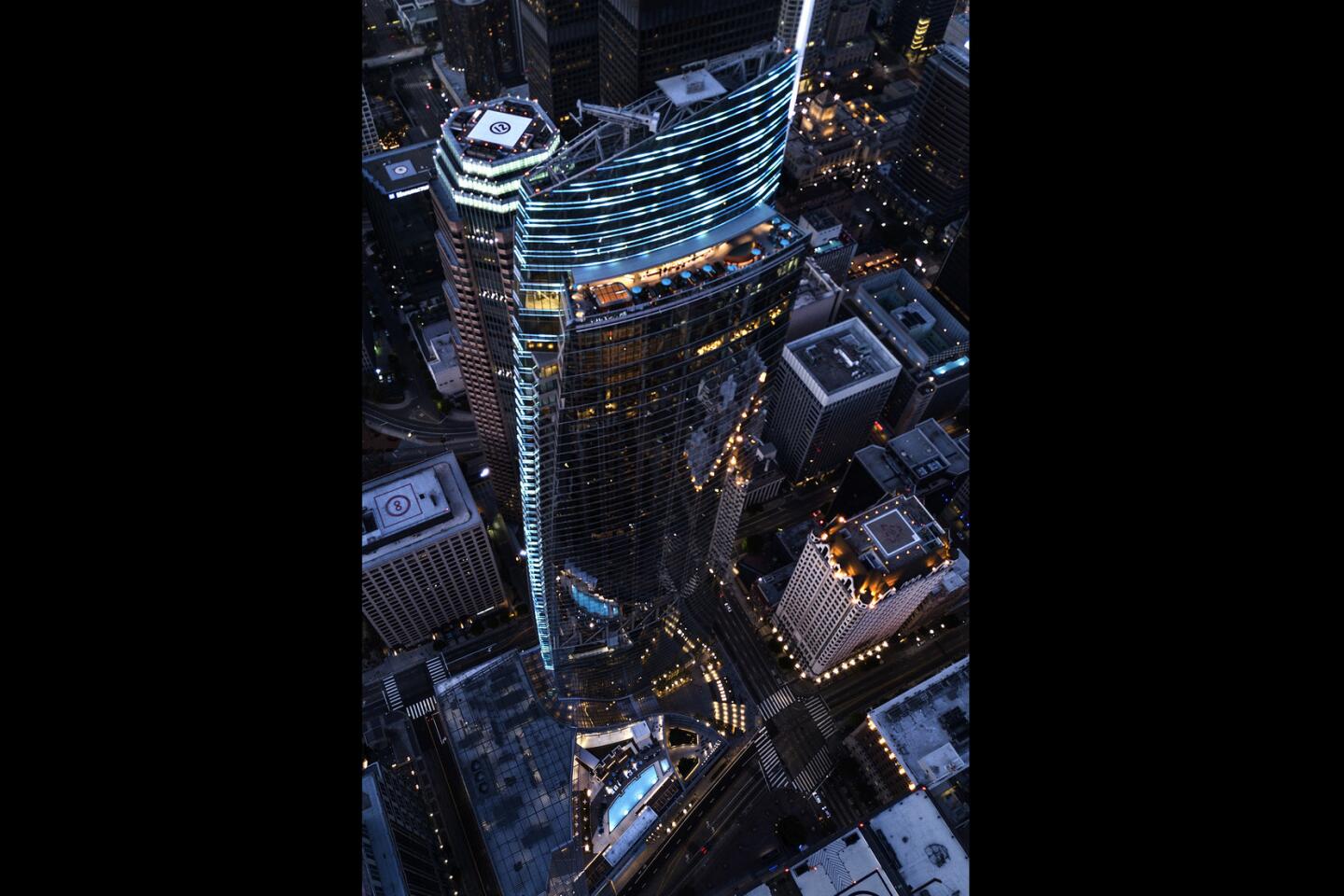

Conceived during the height of the recession as two towers — one a hotel and one an office — the Wilshire Grand eventually was consolidated into one, driving the height to 73 stories.

Given its complexity, architect Michael Maltzan, whose projects include the apartment complex One Santa Fe and the new 6th Street Bridge, wants to wait before passing judgment.

“The ability to measure its impact is complicated by time,” he said. “A tower, a building of that scale, functions at so many different scales, each of which is measured in different time frames, so it is hard to say from Day One if it is a success or not.”

He cited a few object lessons: The Eiffel Tower and San Francisco’s Transamerica Pyramid were mocked at their debuts and today are beloved icons. The U.S. Bank Tower, completed in 1989 a few blocks away from the Wilshire Grand, also received mixed reviews. One critic overlooked the design of what was then the city’s tallest structure, focusing instead on its “dizzying, seven-year exercise in deal-making.”

Some question whether the Wilshire Grand deserves iconic status. Its claim over the U.S. Bank Tower, they say, is a cheat, based on a spire that gives it an 82-foot advantage.

And if spires count, they add, then what about a 1,215-foot smelter smokestack in Magna, Utah?

Yet part-building, part-spire, the Wilshire Grand already has shifted Los Angeles’ conception of what its skyline can be — no longer the flat-topped relics of an era that privileged helipads over ornamentation.

For architect Eric Owen Moss, however, any discussion of merit based on height is antiquated. Moss, former director of the Southern California Institute of Architecture, recently designed a 17-story tower near the La Cienega-Jefferson light rail station.

“I’m sure it matters to the developer, but I’m not sure if it matters to the city or to the community downtown at all,” he said.

More interesting to Moss is whether or not the Wilshire Grand offers a new understanding of what a tower can be. He wondered how the building will interact with the street or if it will advance a new conception of the city.

“You get to be the biggest building if you demonstrate you have the biggest or most substantial content,” he said.

::

A 60-second ride in a service elevator took Martin to the top floors.

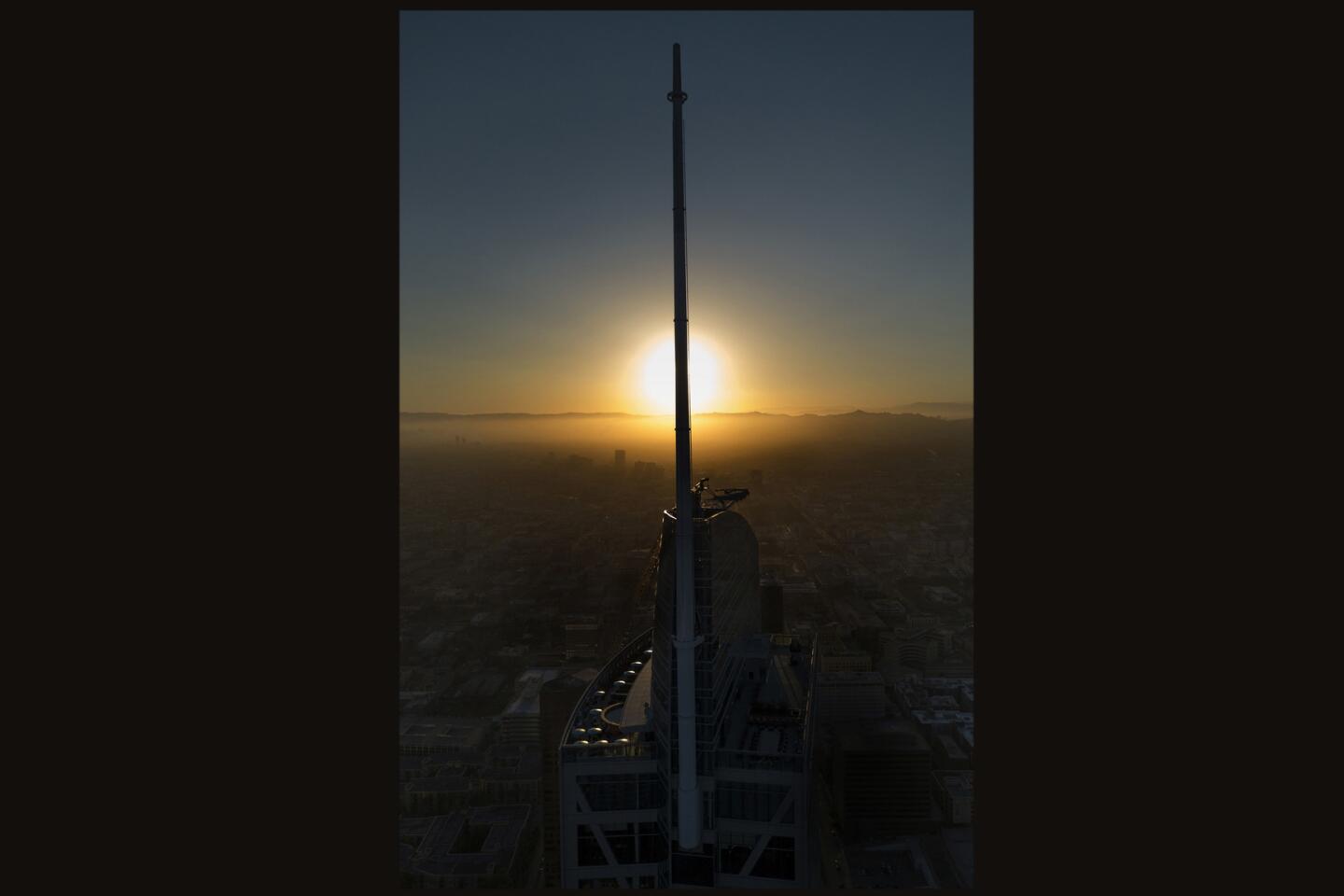

Others may peer at the city, which from this perspective seems oddly miniaturized, but as he stepped onto the terrace on the 73rd floor, Martin turned to study the steel-and-glass sail, a technical achievement rising an additional 300 feet above him.

A skyscraper, Martin said, is often boring: a big box designed for utilitarian, commercial purposes with design subservient to the cost and speed of construction.

Pushing against those pressures is part of the architect’s job, and Martin counts the sail and the adjoining spire as one of his successes, an elaborate and costly artifice, a hood ornament by any other name.

As he climbed into the sail, which will be closed to the public, he was surrounded by beams crisscrossing like a cat’s cradle. “It’s like a ship,” he said, proud that this element withstood the months of debates and disagreement.

But he knows that even monumental design is never fixed in time.

Just blocks away is the City National Plaza with its twin towers. Designed in the 1960s by Martin’s father, Albert C. Martin, these two 52-story buildings — the Arco Towers — have long been honored as a model of Corporate-International style, austere in their smoked glass, dignified in their identical pairing.

Yet last year the owners modified the top story of the north tower, changing the color of the glass, adding a ribbon of silver-white around it, and spoiling the symmetry.

::

As the afternoon waned, traffic on the 10 Freeway was a ribbon of cars, creeping in and out of downtown, bumper to bumper.

For all the best intentions and design, the future of the Wilshire Grand is linked to the city. Sprawl — awesome by day and sparkling at night — is one thing, but gridlock, no matter the hour, is another.

For Thom Mayne, one of the city’s preeminent architects, the Wilshire Grand’s success depends on how the city rises up to meet it.

Looking at the future, Mayne, the executive director of the UCLA Now Institute, believes that Los Angeles’ greatest challenge is an anticipated population increase of 1.5 million by 2050.

He argues for the increased densification of the Wilshire Corridor, from downtown to Santa Monica, soon accessible by subway.

To this end the Wilshire Grand, he said, is “useful,” but he added, “it is one single building. What’s important is for it to be followed by housing.”

Without that step, the skyscraper “is just another random building with no broader connectivity, no synergy, no relationship to some broader strategy of how the city is going to grow and what that means to its citizens, again on human terms, on social terms, on cultural terms.”

Los Angeles, he said, must take the next step.

Twitter: @tcurwen

ALSO

L.A.’s new tallest building is poised to become a lightsaber with massive LED displays

Wilshire Grand Center, tallest skyscraper in the West, debuts in downtown Los Angeles

New Wilshire Grand hailed as a ‘gorgeous nest’ for Los Angeles

Column: Ride the U.S. Bank Tower’s glass Skyslide with 70 floors of nothingness below you

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.