After federal probe, state examines need for civil court interpreters

- Share via

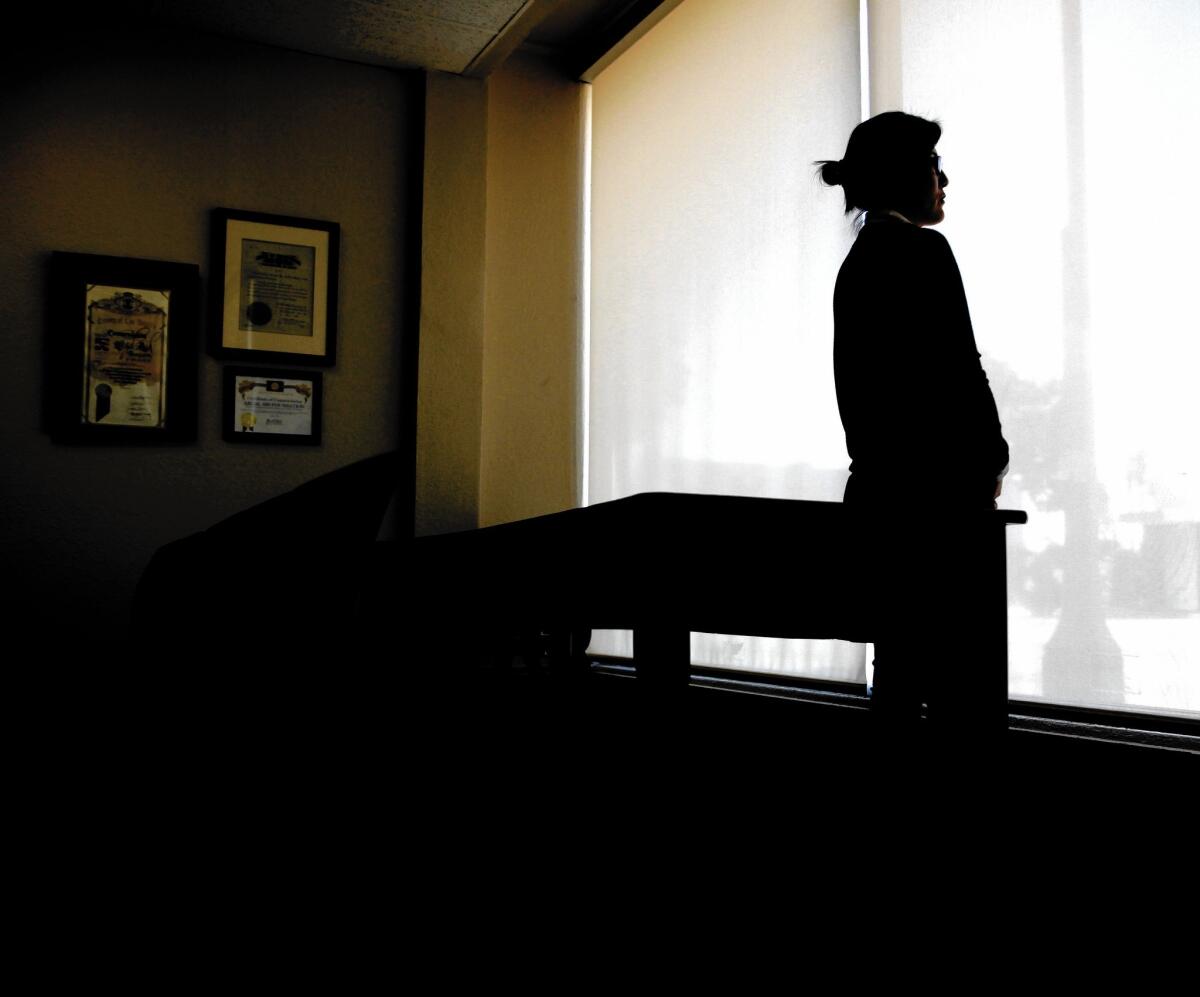

Sung Kyung Hyun calls the year it took to gain custody of her daughter bichamhada. Miserable.

First there was the paperwork, confusing for someone with limited English skills — she had to file it several times before Los Angeles County Superior Court accepted it.

Three times Hyun’s case was postponed because she did not have a Korean interpreter despite having requested one. She took days off work, only to sit helplessly in court.

“Hours would pass and I wouldn’t get called,” Hyun, 41, said in Korean. “All I can do is get up and point to my name and they would just send me away. It was embarrassing.”

Unlike those charged with a crime, people in civil court do not have the constitutional right to an interpreter. For many of California’s nearly 7 million limited-English proficient speakers — about one-third of whom live in Los Angeles County — that makes the system practically impenetrable.

Simple cases drag on. School-age children serve as interpreters because a professional can cost hundreds of dollars a day. Some litigants simply wander the halls, looking for a passerby willing to translate.

The problem led the U.S. Department of Justice last year to conclude that L.A. County and the state’s Judicial Council were violating the Civil Rights Act.

Free language services must be made available in all court proceedings, federal officials said. The investigation found that Los Angeles courts were allowing family and friends to interpret without judging their competence to do so, and that the state had about $8 million in unspent funds allocated for translators that “could have been used to cover thousands of hours of interpreter services without cost.”

The investigation was prompted by a complaint filed by the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles on behalf of two low-income clients. One had been sexually assaulted and sought a restraining order against her attacker; the other had filed for custody and child support for her son. Both were denied Korean interpreters.

Federal authorities have given California the chance to voluntarily improve services. But failure to make the court system accessible to all could result in federal intervention.

Over the last year, a state task force of judges, attorneys, interpreters and court administrators has examined everyday language barriers in the courts — including documents, court staff and inconsistent treatment of interpreter requests.

“This is an issue that has a larger number of moving parts than most people understand,” said state Court of Appeal Justice Maria Rivera, co-chair of the task force.

California, she said, needs a set of uniform standards that can be applied to counties that have vastly different populations and language needs.

A draft of the group’s strategic plan, which was released in July, recommended that each county court set a goal to provide qualified interpreters in all proceedings by 2020. It also proposed recruiting bilingual staff, offering multilingual self-help services, educating judges on working with people who have limited-English skills, translating brochures and websites, and designating employees to oversee language access.

The proposal comes at a difficult time for the state’s court system, which has had to close courthouses and lay off staff in recent years due to budget woes. Rivera said many of the proposed changes are not expected to require additional funding, but the state court system will have to figure out a way to find more money for interpreter services.

The final plan is expected to be presented in January to the Judicial Council, which sets policy for the state’s courts.

More than three dozen legal organizations in the state have expressed their dissatisfaction with the draft proposal, and together submitted a list of suggested revisions.

The group wants an immediate remedy for the indigent population in need of translators, said Joann H. Lee, one of the attorneys who filed the complaint with federal authorities. She criticized the plan for failing to include more input from community members likely to be affected and issuing goals rather than requirements for the courts to follow.

“It’s more sort of like a list of suggestions — we wanted recognition that there was a legal obligation to do this rather than something they thought would be nice for litigants,” Lee said. “All counties should be providing interpreters in all proceedings for everyone.”

Los Angeles County, home to the nation’s largest Latino and Asian populations, makes for a difficult region to serve. More than half of residents speak a language other than English at home and there are about 225 identified languages in the area.

L.A. County Superior Court, the largest single unified trial court in the country with 38 courthouses, employs about 400 certified interpreters and contracts with 200 more to serve approximately 86 languages. Because more than 80% of litigants who have difficulty with English are Latino, Spanish interpreters are provided in certain courtrooms, a court spokeswoman said.

Already providing translators in juvenile, domestic violence, mental health and elder abuse cases, L.A. County’s courts began offering interpreters to low-income litigants in eviction, conservatorship and guardianship cases in May. Still, language access advocates say a large gap remains in family law proceedings, where delays in child custody and child support disputes can have serious consequences.

At a public comment session on language access earlier this year, Sherri Carter — the executive officer and clerk of L.A. County Superior Court — said the limited supply of certified interpreters makes it difficult to expand translator services. The court, she said, already provides translators to a dozen other counties and, for some languages, employs 50% to 100% of available interpreters in the county.

Ariel Torrone, a full-time Spanish interpreter at the Burbank Courthouse, agreed there is a shortage of translators, but said plenty are available for the county’s most-needed languages: Spanish, Chinese, Korean and Armenian. He believes the court could use those interpreters to help people in other types of cases.

“The court has a very narrow definition of cases that need an interpreter,” Torrone said. “But I’ve always felt that what applies to criminal should also apply to the civil courts.”

corina.knoll@latimes.com

Twitter: @corinaknoll

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.