USC president’s aim in teaching a classics course is to ‘light a fire’ for humanities

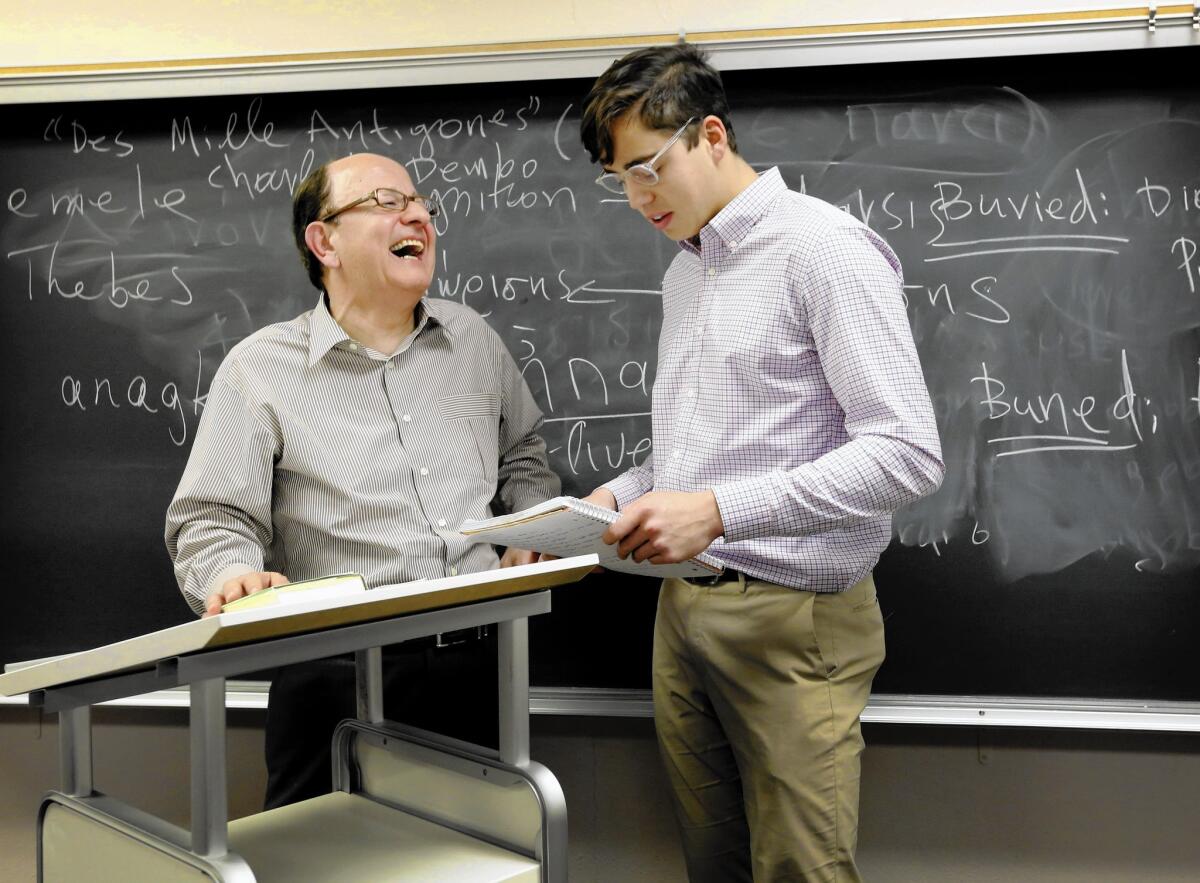

USC President C.L. Max Nikias, left, chatting with a student, is teaching a course on Greek culture this semester -- his first time in the classroom in years.

- Share via

C.L. Max Nikias hasn’t taught a full-time course since becoming USC’s president nearly six years ago.

But in his return to the classroom this semester, the former electrical engineer didn’t focus on circuits or radar but on the ethical implications of the Greek tragedy “Antigone,” demonstrating how one character in the play delivers a fatal, self-inflicted wound.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

An earlier version of this article incorrectly summarized the plot of “Antigone” as the story of a princess who disobeys her father. She disobeyed her uncle.

------------

“The bloodiest way to commit suicide is to drive a sword into your liver,” he said, plunging a fake blade into the left side of his abdomen.

The macabre presentation reflected Nikias’ personal obsession with the classics. But more broadly, it was a display of his determination to boost interest in the humanities at a university best known for its business and film schools, not to mention football program.

Educators throughout the country have long been concerned about declining interest in liberal arts as more students take science, technology and other majors they believe will lead to high-paying jobs. Some schools such as Princeton and Stanford universities have started programs to recruit high schoolers interested in the humanities, but enrollment numbers have continued to dip.

In 2014, 173,000 undergraduates received humanities degrees, down 13,000 from five years earlier, to the lowest level in a decade, according to the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Only 1,278 undergraduates graduated with classical studies degrees in 2014, the lowest total in nine years.

USC has avoided the trend. The percentage of undergraduates majoring in humanities held steady at about 6% over the last five years, and this year’s 25 classic majors mark a recent high. But Nikias said he would like to see those numbers increase.

“Humanities teach you to read and to think and to self-teach, which are the most important things,” Nikias said. “I want to see if I can light a fire in the students myself.”

Nikias’ love of the classics began when he was age 10, after his godfather took him to see a staging of “Oedipus Rex” in Greek at a theater in his native Cyprus, a Mediterranean island with large ethnic Greek and Turkish populations. On the way to the show, Nikias’ godfather told him the entire story of the Sophocles tragedy of the king of Thebes who would kill his father and marry his mother.

“It’s not about being surprised by the plot, it was about the lessons and tensions in the play,” Nikias said. “I became very passionate about them, and once you get [interested] at that age, it never leaves you.

Nikias earned his undergraduate degree from the National Technical University of Athens, and master’s and doctorate degrees from the State University of New York at Buffalo, all in engineering. But he kept up with his interest in the classics, rereading many of them each year and filling book shelves with critical studies of the plays. He even watched Spike Lee’s latest film, “Chi-Raq,” because it was based on the Greek comedy “Lysistrata.”

Another reason to watch the movie: “Spike is a big USC football fan,” Nikias said.

Earlier in his career, Nikias taught engineering courses and more recently led short introductory classes for freshman. He considered teaching a classics course several years ago but was too involved in fundraising.

But with the fundraising campaign ahead of schedule —- donations recently passed $5 billion — Nikias tapped Thomas Habinek, a professor in USC’s classics department, to co-teach a semesterlong course called “The Culture of Athenian Democracy.”

Sixty-four students applied for the 30 slots in the class, which is restricted to freshmen and sophomores. Many students said they were excited to take a class with Nikias. But at the beginning of a recent class, the undergraduates seemed almost shy. No one dared to check his Instagram account or pull out her laptop.

“Nobody told us we couldn’t, it’s just that you want to bring your A-game to a class being taught by the school president,” said Benjamin Williams, a sophomore.

Nikias stood at the front of the classroom, his sleeves rolled up, lecturing on his favorite play, “Antigone,” the story of a princess who disobeys her uncle, coaxing students to read parts. “I need a Antigone, I need a chorus,” he said.

The students were fully engaged, debating the importance of order in society and the obligations of family, as Nikias paced in front of the classroom, chewing on his eyeglass frames and occasionally offering his opinions.

He is drawn to Antigone, he said, because the main character is willing to stand up for herself, albeit with tragic results. (Spoiler alert: Just because you’re the title character doesn’t mean you live).

“I’m fascinated [the playwright Sophocles] chose a woman as a hero in a male-dominated society,” Nikias said.

He said he sees parallels between Antigone’s attitudes and modern life. When students protested outside his office last fall, Nikias said he was actually pleased.

“They’re all Antigones,” he told the class.

Nikias and the students have grown more comfortable in their exchanges. When discussing “Oedipus Rex,” Nikias playfully rolled his eyes when asking students if they believed one of Habinek’s interpretations of the tragedy.

Habinek suggested that Oedipus didn’t actually kill his father and only confessed to the deed as a way to protect his plague-cursed kingdom from further punishment, a theory Nikias doesn’t subscribe to. “He did it,” Nikias said.

Sophomore Joseph Bae was emboldened to challenge Nikias, arguing that Habinek’s position was valid.

Bae later said he might have been too shy to speak in front of the president earlier in the semester. “There was a little worry that you’d say something dumb, but now if I have a question, I’ll ask it.”

The course, he said, has broadened his perspective and stoked interest in taking more humanities courses, probably philosophy.

“I really like that there are two sides to everything,” Bae said. “It’s not like an organic chemistry class where there’s just one answer.”

Twitter: @byjsong

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.