Cement masons union leader subject of U.S. investigation

- Share via

A union leader whose members helped construct Disney Hall, Staples Center and other signature Southern California buildings is under investigation over allegations that he let employers skip payments to workers’ health and pension funds, spent dues money on an extramarital affair and retaliated against whistle-blowers.

Scott Brain represents about 1,650 workers as head of Cement Masons Union Local 600, based in Bell Gardens. The union is a force in local and state politics as a regular donor to election campaigns.

Its collective bargaining agreements require construction companies to contribute money to trusts that fund workers’ medical care, retirement plans and other benefits.

The union trusts accused some employers of failing to make millions of dollars in such payments, court records and trust documents show.

Brain supported efforts to remove an audit director for the trusts who had complained about the missing payments, according to trust records that have been turned over to federal investigators.

The director was placed on leave after she began cooperating with the investigation of Brain by the U.S. Department of Labor. She was subsequently discharged and has filed a wrongful termination suit.

Among the allegations under investigation is that Brain, business manager of Local 600, spent union funds on an affair with Melissa Cook, an attorney retained by the trusts.

Brain signed Cook’s checks, and her firm’s fees for representing the trusts increased significantly on his watch, billing records show.

Cook resigned from the trusts after a federal agent called her in May and asked if she was having an affair with Brain, said people familiar with the events.

In a brief phone interview, Brain said of the allegations: “Wow, I probably shouldn’t comment. There’s nothing there.”

Local 600’s attorney, Jeffrey Cutler, said Brain had no motive to allow contractors to withhold benefit payments. He said federal investigators “have never asked to interview Mr. Brain.”

Cook, who runs a San Diego law firm, said the fees the trusts paid her firm were proper. She said she would not discuss “any personal matter” involving Brain.

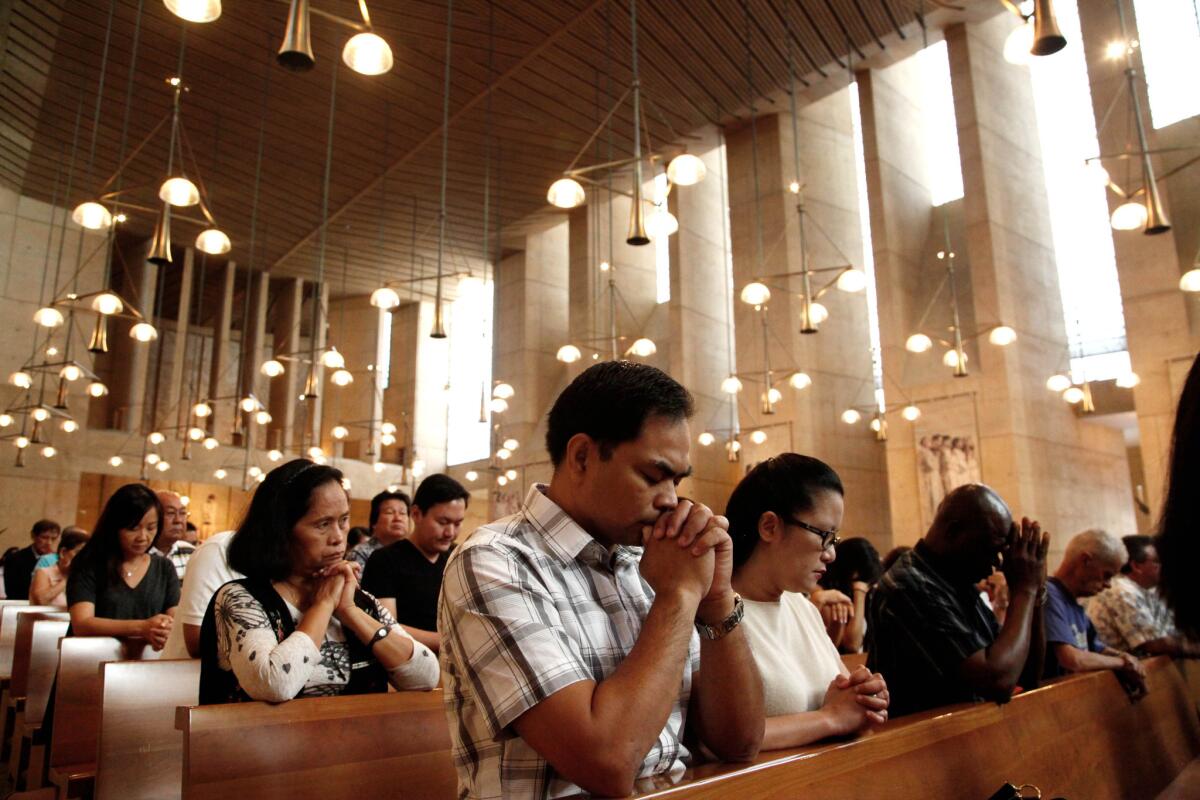

Members of Local 600 have left their stamp on fire stations, schools and civic buildings from Los Angeles to the Central Coast. Their skilled labor is visible in the columns and courtyards of such landmarks as the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels.

The recession hit the union hard, and much of the recovery has passed the workers by. Masons who once worked enough hours to earn $80,000 a year make as little as $45,000 today.

Collecting every penny for their benefit trusts is crucial, because the contributions stop whenever the workers are between jobs.

A Labor Department investigator has served subpoenas on the union and the trusts, obtaining records on 10 contractors that employed Local 600 members and other documents.

People questioned by federal agents said they focused on two companies that, the trusts alleged in court records, failed to make about $4 million in payments: B&M Contractors Inc. of Simi Valley and the now-defunct A&G Custom Concrete and Repair of Riverside.

The absence of the payments was confirmed through audits by the trusts in 2008, the court records show.

Cheryle Ann Robbins, then audit and collections director for the trusts, addressed the matter with the trust boards, according to minutes of the panels’ closed-door meetings, which the Labor Department has subpoenaed.

The minutes for one meeting show that Robbins and a trustee voiced suspicions that Brain allowed A&G to withhold the payments, although a company representative denied that to board members.

Robbins told The Times that Brain confronted her in the office parking lot after the meeting and warned her not to press the issue.

“He said I could lose my job,” she said.

Principals in B&M and A&G said union representatives led them to believe that their contracts with Local 600 required them to make contributions only for some workers in limited circumstances.

“Nobody ever told us to make any payments,” said Dave Moore, a partner in B&M.

The wrangling over the contributions led to several lawsuits. The two firms eventually agreed to pay a combined $750,000, about 19% of what the trusts alleged they owed, according to the meeting minutes and other records.

Cook represented the trusts in the B&M dispute. Citing the 2008 audit, Cook said in court papers that the company owed the trusts $2.9 million. In an interview, however, she said the audit had exaggerated the amount owed and that the $400,000 B&M paid in the settlement was closer to the actual figure.

Robbins disputed that, saying the $2.9 million was determined by examining the company’s payroll records.

After the settlements, Robbins said, Brain intervened on behalf of a contractor that owed the trusts more than $30,000. According to the meeting minutes, Brain said the contractor owed less than that, and the amount was reduced to about $5,200.

In 2011, with Brain’s support, the trustees began to expand Cook’s role as counsel to the trusts, giving her responsibility over audits and collections, records and interviews show. The trustees later dropped another law firm that handled audits and collections and gave the work to Cook.

The new assignment increased her firm’s compensation by about $300,000 over the next 17 months, to more than $500,000 total, according to billing records and interviews.

The fees for audits and collections were about three times the average monthly amount paid over the previous two years to the firm that Cook’s replaced, a trust financial statement shows.

Cook said the increased payments were deserved because her firm did more work than the other one. Many of her firm’s billings resulted from the Labor Department investigation and Robbins’ wrongful termination suit, Cook said.

The federal probe began in October 2011. Acting on a complaint from another person associated with the union, a Labor Department agent asked Robbins to cooperate, according to those knowledgeable about the investigation.

Robbins said the agent served a subpoena on the trusts about a month later, and she started gathering documents. She was placed on paid leave the next day, records show.

Meeting minutes state that the trustees put Robbins on leave after discussing whether she mishandled the Labor Department inquiries by not informing them or their attorney of the investigators’ interest in Brain.

Two days after she was put on leave, Robbins said, someone broke into her house and stole day planners she used at the trusts and folders of receipts. A police report on the incident said the house appeared to have been ransacked.

A mother and son who worked for a benefits administration company the trusts employed said they were terminated soon after Robbins was placed on leave because they sided with her in the disagreements with Brain. A company manager said they were let go for other reasons.

Robbins was dismissed in April 2012, after the trusts hired a company to run the audit and collections department. She was the only trust employee not kept on by the company.

A trustee who supported Robbins’ removal, David Baldwin, broke with Brain on the decision to give Cook the collections work and later came to suspect they were having an affair, according to meeting minutes and union sources.

Baldwin, a Local 600 business representative, told his fellow trustees in May that he believed Brain’s relationship with Cook could violate conflict-of-interest laws, something the federal agents are investigating, the sources said.

Baldwin presented the trustees with a union-paid bill for a Fort Lauderdale, Fla., hotel room reserved last March in the names of “Scott and Melissa Brain,” according to the sources.

He also provided the trustees with photographs, taken by a third party, that showed Brain and Cook in intimate embraces, the sources said.

The Times reviewed the hotel bill and the photos, which the sources said are in the hands of federal investigators.

The agents are also examining about $12,000 in other charges for meals and lodgings that Brain paid with his union credit card over nearly two years, people with knowledge of the probe said.

In July, Brain removed Baldwin from the trusts.

Baldwin declined to comment.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.