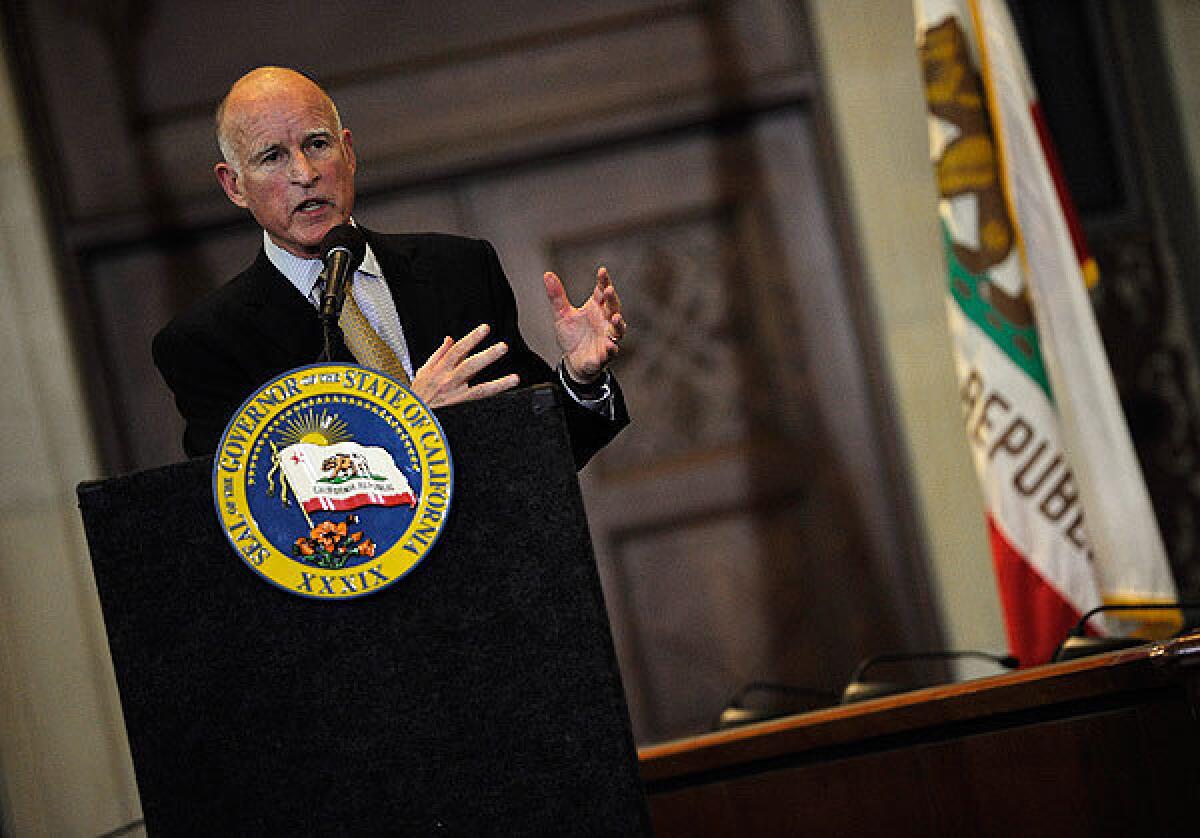

Acrobat Brown does a flip on tax hike measure

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — Back in the day, when Gov. Jerry Brown would dazzle us with a flip-flop, he’d land on his feet spouting philosophy.

“A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds,” he’d intone, quoting Ralph Waldo Emerson.

The best-known Brown acrobatic was his turn-around on Proposition 13, the revolutionary initiative by apartment owners’ lobbyist Howard Jarvis that dramatically slashed property taxes.

Brown loudly opposed the measure when it was on the 1978 primary election ballot. But after voters passed it by 2 to 1, he proclaimed himself a “born-again tax cutter.” The governor became so enthusiastic in implementing Prop. 13 that he earned the nickname “Jerry Jarvis.” And Jarvis endorsed him that fall for reelection.

The first significant flip of his second act as governor — maybe it isn’t a total flip-flop, but it’s a big leap nevertheless — was performed Wednesday when he reshuffled his position on increasing taxes.

“The life of politics is something that changes and evolves,” Brown told reporters who asked for an explanation of why he was suddenly switching directions.

“I don’t have an ego in this.”

“My goal is to balance the budget. It’s been in disarray for more than a decade in California.”

The governor basically got rolled by the California Federation of Teachers, the smaller of the two major teachers unions. The largest union, the California Teachers Assn., had endorsed Brown’s original tax-hike initiative.

Brown cut a deal with the CFT to avoid butting heads on the November ballot with its “millionaires’ tax,” which would have socked the rich hard but absolutely no one else. Punching multimillionaires is particularly popular these days as the gap widens between the haves and have-nots.

But the governor had argued, as late as Monday, that his original proposal was better public policy because it was “balanced” — burdening everyone slightly with a half-cent sales tax increase, and capping the wealthy with a relatively modest hike in the income tax.

The Brown-CFT deal would cut his sales-tax hike in half. And it would smack the wealthy more than the governor had wanted — raising state income-tax rates by one percentage point for single-filers earning more than $250,000; by two points for those making more than $300,000; and by three points on earnings exceeding $500,000. Currently, the top rate for million-dollar earners is 10.3%.

The income-tax increases would last seven years, rather than five, as Brown originally proposed. The tiny sales-tax hike would last four years.

The reshaped proposal is bound to be more popular with the electorate than Brown’s original. A larger share of the tax load would be shifted to fewer voters.

But it’s poor public policy. Although it may be satisfying for the majority, smacking the rich worsens a California tax system that badly needs to be overhauled.

The top 1% already pay roughly 40% of the state income tax. This results in an extremely volatile revenue roller-coaster. In boom times, the rich prosper and pour money into the state vault. During periods of bust, their capital gains dwindle and so does the state’s revenue stream. The state suffers budget deficits. Schools, universities and the poor people’s safety net are slashed.

But this is what Brown and Democrats were thinking Wednesday: “It dramatically increases our chances of success in November,” said Senate leader Darrell Steinberg (D-Sacramento).

“The most important thing was to broaden the coalition,” the senator explained, meaning to get the CFT off Brown’s back. If both their measures were competing on the ballot, odds are neither would have passed.

Brown’s next move should be to coax aside another tax measure — one by mega-rich civil rights attorney Molly Munger. She proposes raising income taxes on all but the poorest and generating $10billion, primarily for schools.

Munger’s proposal has the least chance of passing because it would force virtually all voters to pay higher taxes. But the measure could drag down Brown’s with it.

All three measures — the governor’s, the CFT’s and Munger’s — have been in the process of qualifying for the ballot through voter signature-collecting.

Brown’s tax flip would add $2 billion to the roughly $7 billion he had figured on netting the state immediately.

Schools would get a significant amount — it wasn’t known at this writing how much, maybe a third — and the rest would help balance the budget, preventing additional cuts in university funding, public safety and programs for the poor.

Of course, the Democratic governor also must hold the business lobby in check. It could mount an aggressive anti-tax campaign in November.

The influential state Chamber of Commerce and California Business Roundtable had not taken a position on the governor’s proposal. But last week both declared their strong opposition to the CFT and

Munger initiatives because of the hefty income-tax increases.

Now that Brown has acquiesced to soaking the rich they might frown on his plan, too.

One invaluable asset the business lobby has gained, however, is more leverage over the governor.

If he wants to recruit it as an ally in the tax battle, Brown better be willing to deliver some meaningful business regulatory relief, at a minimum.

Everyone now knows the philosopher governor will compromise and — when necessary — bend, roll and flip.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

![Vista, California-Apri 2, 2025-Hours after undergoing dental surgery a 9-year-old girl was found unresponsive in her home, officials are investigating what caused her death. On March 18, Silvanna Moreno was placed under anesthesia for a dental surgery at Dreamtime Dentistry, a dental facility that "strive[s] to be the premier office for sedation dentistry in Vitsa, CA. (Google Maps)](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/07a58b2/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2016x1344+29+0/resize/840x560!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F78%2Ffd%2F9bbf9b62489fa209f9c67df2e472%2Fla-me-dreamtime-dentist-01.jpg)