Asian immigrants less likely to seek deportation protection, data show

- Share via

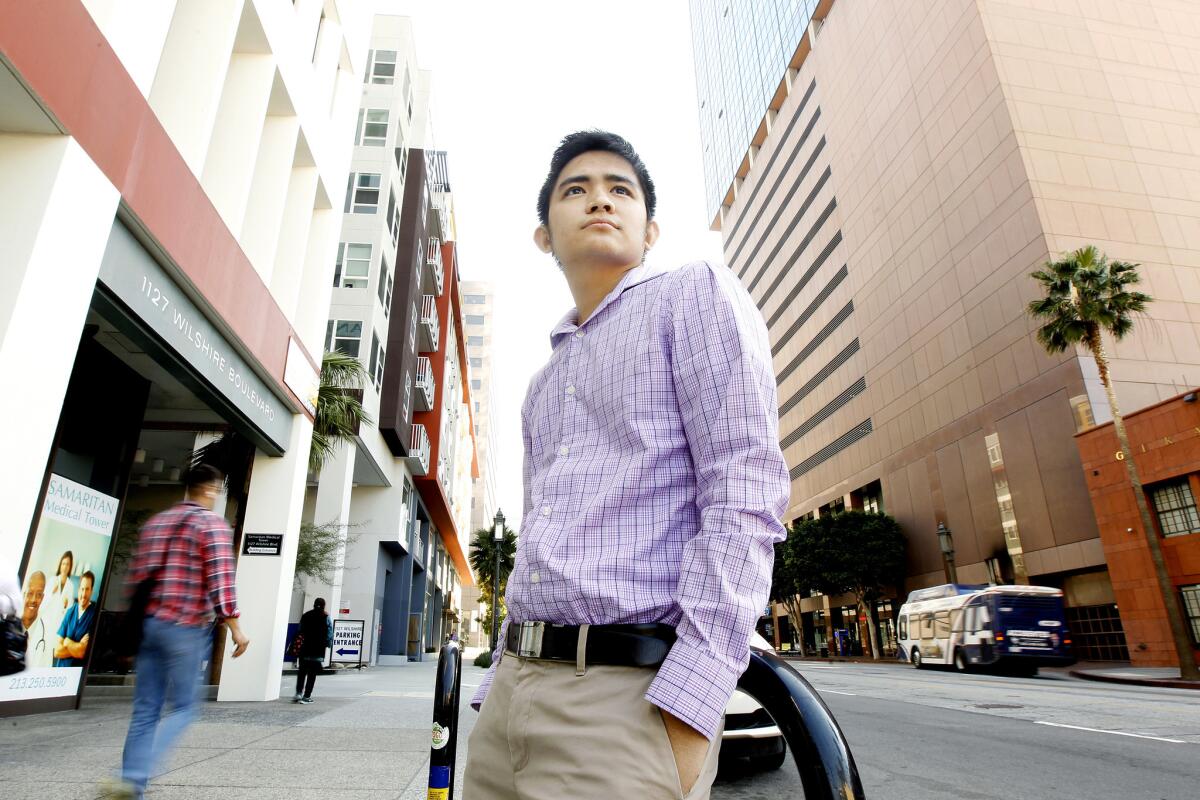

Anthony Ng was in high school when he realized he didn’t have permission to live in the United States. The summer internship he had landed in Washington, D.C., required participants to submit Social Security numbers. Ng didn’t have one.

A Filipino immigrant whose parents brought him to Los Angeles illegally at age 11, Ng had never asked about his immigration status. It’s a topic rarely discussed in the Filipino community, where the Tagalog term for those in the country illegally is a pejorative that means “always in hiding.”

------------

FOR THE RECORD: A previous version of this post said that 62% of eligible Salvadorans had applied. Among eligible Salvadorans, 44% applied.

------------

In 2012, when President Obama launched a program offering temporary work permits and protection from deportation to immigrants who came to the U.S. as children, Ng eagerly applied.

He was an anomaly.

While Latinos have signed up for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program in large numbers, Asian immigrants have not. According to federal data analyzed by the Migration Policy Institute, just 24% of eligible Koreans, 26% of eligible Filipinos and 28% of eligible Indians applied in the program’s first two years.

Youths from China, who are among the most entitled to relief, didn’t crack the government’s list of top 20 application groups. Fewer than 1,610 applied.

Now, with a planned expansion of the program put on hold by a federal judge in Texas, immigrant advocates are worried that the political controversy might make Asians even more reluctant to take part.

“I’ve seen fear and confusion,” said Rep. Judy Chu (D-Monterey Park), adding that some Asian immigrants are wary of sharing personal information with the government and have doubts about whether the program will last.

Since Obama announced in November that he was expanding his signature immigration initiative to include deportation protections for a broader group of childhood arrivals, as well as up to 4 million immigrant parents of U.S.-born children, advocates have been scrambling to make sure Asians are better represented.

Legal aid and advocacy groups have bolstered outreach through ethnic media outlets and opened satellite offices in growing immigrant outposts such as the San Gabriel Valley. The first step, activists say, is initiating conversations about immigration status.

“We need to reach out and demystify the stigma,” said Mee Moua, executive director of Asian Americans Advancing Justice, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group. “It’s not enough to tell people there’s this executive action and here are the benefits. We need to pause and say: ‘If you are sitting here feeling like you’re the only person who is undocumented, you should know that there are many people in this county or this state who are Asian American and in your same situation.’”

Annie Kao, 22, used to change the subject when high school friends talked about their Social Security numbers or asked why she didn’t have a driver’s license. “There’s a lot of shame,” said Kao, a Taiwanese immigrant brought to the U.S. illegally by her grandmother at age 12.

But after she enrolled at UCLA, a group of student activists encouraged Kao to share her positive experience with the deferred action program with other immigrants. She now answers calls for a hot line for Chinese immigrants who have questions about deferred action or other paths out of the shadows.

Speaking in Mandarin at a recent news conference for ethnic media outlets, Kao asked immigrants from her community to engage in the immigration debate.

“This is not just a Latino issue,” Kao said. “We can take ownership of our stories.”

In the first two years of the deferred action program, 68% of eligible Hondurans, 62% of eligible Mexicans and 61% of eligible Peruvians applied.

Experts say there are a number of reasons why Latinos have participated in deferred action at twice or three times the rate of some Asian immigrants.

One is the sheer size of the Latino immigrant population — and that community’s growing political clout. About 9.2 million immigrants in the country illegally were born in Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean or South America, compared with 1.5 million born in Asian or Pacific Island countries.

Language also may play a role: Advocates trying to reach Latinos can do it largely in Spanish, while those trying to speak with Asians must do so in multiple languages.

Tom Wong, a professor at UC San Diego, said the barriers to Asian participation may go beyond issues of visibility and cultural stigma.

Asians “don’t feel the threat of deportation as acutely” as Latinos, who are deported at a higher rate, he said. And some Asian immigrants may have other forms of relief available to them. “It may be a rational and conscious choice not to apply because the benefits do not outweigh the cost,” he said.

Aquilina Soriano, executive director of the Pilipino Workers Center, noted that Asian immigrants have less experience participating in past immigration relief programs. Mexican nationals were the primary beneficiaries of the 1986 amnesty bill, and Hondurans and Salvadorans have enjoyed a special immigration benefit called Temporary Protected Status for more than a decade.

“Folks are a little bit more wary because they don’t have that experience,” Soriano said.

Her group has been using community media to encourage Filipinos to apply for deferred action as well as California’s new immigrant driver’s licenses.

“We fought for this right,” she said at a recent event with the Philippine Consulate General in Los Angeles. “As we create more of a critical mass of people accessing these benefits, hopefully it will allay their fears,” she said.

Those who support deferred action say robust participation is the best way to defend the program against attacks. They believe the more immigrants who are enrolled in the program, the harder it will be for a future president to undo it.

Obama announced in November that he would use his executive authority to shield millions from deportation, saying he wasn’t going to wait for Republicans to fix a broken immigration system. Soon after, 26 states — mostly controlled by Republican governors — went to court to block implementation of his plan, saying Obama overstepped his legal authority.

On Monday, a federal judge ordered a temporary halt to the program. The administration announced Friday that it would seek an emergency order from an appeals court to reverse the injunction.

Ng, who is now 25 and working at Asian Americans Advancing Justice, said uncertainty about the fate of the program makes outreach to immigrant communities all the more critical.

“It creates a level of confusion,” he said. “But we believe it’s a small bump in the road.”

For more news on immigration, follow @katelinthicum.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.